Volodymyrets

Varash district, Rivne region

The town may be listed under Ukraine, Poland, Russia (USSR), or Belarus (White Russia). Variations on the name include: Vladimerec, Vlodimiretz (Yiddish), Wladimirets (German), Volodymyrets (Ukranian) and Wlodzimierzec (Polish). It is also often confused with Vladmir Volynsk or Vladymir Volinskij (Russian) because that town is the Vladimirets in the Vohlyn region. The two towns also have similar names in Yiddish, which has added to the confusion.

Since 1795 - as part of the Russian Empire. In the 19th - beginning of the 20th century - the town of Lutsk district of the Volyn province. In 1919–39 - in the Volyn Voivodeship as part of Poland, in 1939–91 - as part of the Ukrainian SSR.

In 1765, 110 Jews lived in Vladimirets,

in 1787 - 64,

in 1847 - 251,

in 1897 - 1024 (49.3%),

In 1921 - 1263 Jews (43%).

Unlike some shtetls, Vladimirets never had a "Jewish Ghetto" – Jews and non-Jews lived as neighbors until the 1940's when Nationalist Ukrainians working with the Nazis began rounding up outlying Jews and bringing them to Vladimirets. The 1939 census shows a thriving Jewish community with 1,377 members – today there are no Jews left from before WWII. After the war (1945), some Jews came back to locate survivors or try to find justice. They found neither and did not stay. The last Jew left Vladimirets in 1948 for Israel.

Since 1795 - as part of the Russian Empire. In the 19th - beginning of the 20th century - the town of Lutsk district of the Volyn province. In 1919–39 - in the Volyn Voivodeship as part of Poland, in 1939–91 - as part of the Ukrainian SSR.

In 1765, 110 Jews lived in Vladimirets,

in 1787 - 64,

in 1847 - 251,

in 1897 - 1024 (49.3%),

In 1921 - 1263 Jews (43%).

Unlike some shtetls, Vladimirets never had a "Jewish Ghetto" – Jews and non-Jews lived as neighbors until the 1940's when Nationalist Ukrainians working with the Nazis began rounding up outlying Jews and bringing them to Vladimirets. The 1939 census shows a thriving Jewish community with 1,377 members – today there are no Jews left from before WWII. After the war (1945), some Jews came back to locate survivors or try to find justice. They found neither and did not stay. The last Jew left Vladimirets in 1948 for Israel.

Community Life

The Jewish community in Vladimirets was diverse. There were at least 6 shuls (synagogues): Trisk Chasidim, Stepan Chasidim, Stopan Chasidim, the Craftsman's Synagogue, and Conservative. There were also many “shteibels” [usually a one-room building just for davening], study groups and minyans held in people's homes. There was no orthodox/non-orthodox distinction – it was only observant or less observant Many families who went to Chassidic shuls would not align themselves with the ultra-orthodox Chasidim once they left Vladimirets.

Several of the shuls had schools (cheders or Talmud Torahs) associated with them and most Jews (including the women) were well educated. Most could read and write – often in several languages. The shul was the hub of the Jewish social community as well as the religious center. Everyone would have attended shul every Shabbos (Shabbat) for the chance to see friends and family they didn't get to see during the week.

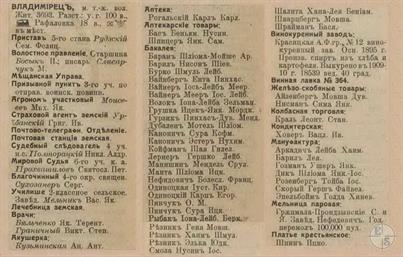

Typical of Jewish shtetls, Vladimirets was not a wealthy community. Because of the laws, Jews weren't allowed to own land or anything that hadn't been owned before, which meant that most Jews were merchants of some sort. One Jew, however, owned the grain mill in town. Others were carpenters and shokhets (ritual slaughterers), junk men and furniture makers, and of course, teachers and rabbis. Given the time and conditions, the Jewish families of Vladimirets were doing reasonably well for themselves.

In 1913, Jews owned most shops in the town - 39.

In the 19th - 20th centuries the rabbis in Vladimirets were representatives of the Shalita family -Shloyme-Yakov, Jehuda-Leib, Benjamin, from 1880 - Itshok-Eli (1851–?), in the 1910s - Shloyme-Yakov (? –1942).

In 1921, a Jewish school opened in Vladimirz, but six months later it was closed by order of the authorities. Jewish children studied in Polish public schools, private teachers taught Hebrew and Torah.

During the Soviet occupation, at the end of 1939, a Soviet school was opened in which Yiddish was the language of training and in which 210 students studied.

Most Jewish families emigrated from Vladimirets between 1900 and 1930. While many came to the United States or Canada, others settled in British Palestine (Israel) and South America. Of those who came to the United States, most settled in Detroit, Michigan, or at least started out there. Other major draws were New York City and Boston. Canadians would land at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and migrate to Montreal or Toronto.

Zionism was strong in Vladimirets and the surrounding Vohlyn region. Vladimirets supported multiple Zionist youth groups. Some were able to make aliyah and emigrate to Israel, then British Palestine. In some ways, it was easier to emigrate to America. The local rabbis were split – while they all agreed that living in Eretz Yisrael was better, some actively discouraged moving to the United States because of the fear that they would lose their jewishness.

The Jewish community in Vladimirets was diverse. There were at least 6 shuls (synagogues): Trisk Chasidim, Stepan Chasidim, Stopan Chasidim, the Craftsman's Synagogue, and Conservative. There were also many “shteibels” [usually a one-room building just for davening], study groups and minyans held in people's homes. There was no orthodox/non-orthodox distinction – it was only observant or less observant Many families who went to Chassidic shuls would not align themselves with the ultra-orthodox Chasidim once they left Vladimirets.

Several of the shuls had schools (cheders or Talmud Torahs) associated with them and most Jews (including the women) were well educated. Most could read and write – often in several languages. The shul was the hub of the Jewish social community as well as the religious center. Everyone would have attended shul every Shabbos (Shabbat) for the chance to see friends and family they didn't get to see during the week.

Typical of Jewish shtetls, Vladimirets was not a wealthy community. Because of the laws, Jews weren't allowed to own land or anything that hadn't been owned before, which meant that most Jews were merchants of some sort. One Jew, however, owned the grain mill in town. Others were carpenters and shokhets (ritual slaughterers), junk men and furniture makers, and of course, teachers and rabbis. Given the time and conditions, the Jewish families of Vladimirets were doing reasonably well for themselves.

In 1913, Jews owned most shops in the town - 39.

In the 19th - 20th centuries the rabbis in Vladimirets were representatives of the Shalita family -Shloyme-Yakov, Jehuda-Leib, Benjamin, from 1880 - Itshok-Eli (1851–?), in the 1910s - Shloyme-Yakov (? –1942).

In 1921, a Jewish school opened in Vladimirz, but six months later it was closed by order of the authorities. Jewish children studied in Polish public schools, private teachers taught Hebrew and Torah.

During the Soviet occupation, at the end of 1939, a Soviet school was opened in which Yiddish was the language of training and in which 210 students studied.

Most Jewish families emigrated from Vladimirets between 1900 and 1930. While many came to the United States or Canada, others settled in British Palestine (Israel) and South America. Of those who came to the United States, most settled in Detroit, Michigan, or at least started out there. Other major draws were New York City and Boston. Canadians would land at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and migrate to Montreal or Toronto.

Zionism was strong in Vladimirets and the surrounding Vohlyn region. Vladimirets supported multiple Zionist youth groups. Some were able to make aliyah and emigrate to Israel, then British Palestine. In some ways, it was easier to emigrate to America. The local rabbis were split – while they all agreed that living in Eretz Yisrael was better, some actively discouraged moving to the United States because of the fear that they would lose their jewishness.

World War II Years

On June 26, 1941, about 500 young Jews and non-Jews were sent to the Sarny, where the battalion was formed from them. But when retreating east, all members of the battalion fell into the hands of the Germans, who immediately selected and killed all Jews.

On June 29, 1941, the Soviet government and the army left the town, and for four days Vladimirets was left without power. According to the teaching of some nationalist leaders, Ukrainians arranged a Jewish pogrom. They robbed and killed two Jews opposing them.

After the Germans arrived, Judenrat was created. The head of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, friendly to the head of Judenrat Yakov Aizenberg, restrained his team, and the Jews were not injured.

Jews were forced to hard work. In December 1941, from the Jews confiscated warm things, and they were obliged to pay a ransom. Judenrat, who was not able to collect everything that the Germans demanded, received assistance from the Polish priest Dominic Vavzhinovich and members of his community.

Immediately after Peshah, in April 1942, an open ghetto was created, where Jews from the surrounding villages were also brought. In total, about 3,000 people were concentrated there.

On August 28, 1942, the Jews of Vladimirets were gathered on a market square. While they stood there, Yehiel Smolar called on them to run, and indeed, several hundred fled. Everyone else was taken out of the town where they were shot.

Even before the action, a group of young people invited Judenrat to set fire to the ghetto, but he rejected this proposal.

On the eve of the first campaign, Ukrainian acquaintances of the head of Judenrat Aizenberg awarded him shelter. Aizenberg refused. This behavior of Aizenberg is confirmed by other testimonies: “The chief of the Ukrainian police Mukha came to the chairman of Judenrat, invited him to hide and was ready to hide him. Yakov Aizenberg returned to the ghetto."

Those of the fugitives who were not able to catch were helped by Ukrainian Baptists and Polish peasants. The young of them later joined the partisan detachments.

On June 26, 1941, about 500 young Jews and non-Jews were sent to the Sarny, where the battalion was formed from them. But when retreating east, all members of the battalion fell into the hands of the Germans, who immediately selected and killed all Jews.

On June 29, 1941, the Soviet government and the army left the town, and for four days Vladimirets was left without power. According to the teaching of some nationalist leaders, Ukrainians arranged a Jewish pogrom. They robbed and killed two Jews opposing them.

After the Germans arrived, Judenrat was created. The head of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, friendly to the head of Judenrat Yakov Aizenberg, restrained his team, and the Jews were not injured.

Jews were forced to hard work. In December 1941, from the Jews confiscated warm things, and they were obliged to pay a ransom. Judenrat, who was not able to collect everything that the Germans demanded, received assistance from the Polish priest Dominic Vavzhinovich and members of his community.

Immediately after Peshah, in April 1942, an open ghetto was created, where Jews from the surrounding villages were also brought. In total, about 3,000 people were concentrated there.

On August 28, 1942, the Jews of Vladimirets were gathered on a market square. While they stood there, Yehiel Smolar called on them to run, and indeed, several hundred fled. Everyone else was taken out of the town where they were shot.

Even before the action, a group of young people invited Judenrat to set fire to the ghetto, but he rejected this proposal.

On the eve of the first campaign, Ukrainian acquaintances of the head of Judenrat Aizenberg awarded him shelter. Aizenberg refused. This behavior of Aizenberg is confirmed by other testimonies: “The chief of the Ukrainian police Mukha came to the chairman of Judenrat, invited him to hide and was ready to hide him. Yakov Aizenberg returned to the ghetto."

Those of the fugitives who were not able to catch were helped by Ukrainian Baptists and Polish peasants. The young of them later joined the partisan detachments.

Sources:

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia. Translated from Russian by Eugene Snaider

- Terryn Barill. Vladimirets

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- The All South-Western Territory: reference and address book of the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Printing house L.M. Fish and P.E. Wolfson, 1913

- World Association Of Wolynian Jews in Israel. Wldomierzec

Photo:

- The New York Public Library. Yizkor Book Collection. Sefer Vladimerets

- JewishGen. The History of Jewish Life in Vladimirets

- Center organizations of Holocaust survivors in Israel. Vladimirets

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia. Translated from Russian by Eugene Snaider

- Terryn Barill. Vladimirets

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- The All South-Western Territory: reference and address book of the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Printing house L.M. Fish and P.E. Wolfson, 1913

- World Association Of Wolynian Jews in Israel. Wldomierzec

Photo:

- The New York Public Library. Yizkor Book Collection. Sefer Vladimerets

- JewishGen. The History of Jewish Life in Vladimirets

- Center organizations of Holocaust survivors in Israel. Vladimirets

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine