Stepan

Sarny district, Rivne region

Sources:

- I. Ganuz and J. Peri. Our town Stepan. Edited by Yitzchak Ganuz, Tel Aviv, Stepan Society, 1977. Translated by JewishGen, Inc.

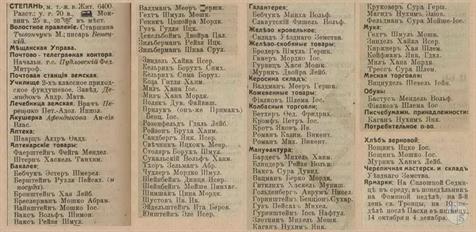

- The All South-Western Territory: reference and address book of the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Printing house L.M. Fish and P.E. Wolfson, 1913

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

Photo:

- European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Stepan Jewish Cemetery

- Aleksander Kraushar (1914), Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. Stepan

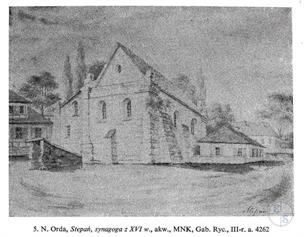

- Romek Pawluk. Synagogue in Stepan in the drawing of Napoleon Orda

- David Shay. A monument to the memory of Stepan's Jews in Holon cemetery

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Stepan

- I. Ganuz and J. Peri. Our town Stepan. Edited by Yitzchak Ganuz, Tel Aviv, Stepan Society, 1977. Translated by JewishGen, Inc.

- The All South-Western Territory: reference and address book of the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Printing house L.M. Fish and P.E. Wolfson, 1913

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

Photo:

- European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Stepan Jewish Cemetery

- Aleksander Kraushar (1914), Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. Stepan

- Romek Pawluk. Synagogue in Stepan in the drawing of Napoleon Orda

- David Shay. A monument to the memory of Stepan's Jews in Holon cemetery

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Stepan

In the era of the Commonwealth, Stepan is the township of Volyn Voivodeship, Lutsk powyat, one of the oldest Volyn city settlements.

At the beginning of the 20th century - the town of Volyn province, Rivne district.

History of the World, by Shimon Dubnov, Vol. 2, page 260, writes: “In 1386, communities existed in the area so one could infer that Jews lived in the Stepan area then. The Turks ruled Crimea. Crimean Jews traded with Jews of Volhynia and some Jews from Crimea moved into Stepan in the 1500's”

Geographical Dictionary for Kingdom of Poland and Other Slavic Kingdoms, Warsaw, 1890, pages 326-327, writes: “In 1890, there were 3,384 people in Stepan, 47% Jewish, 512 households, 3 churches, 1 Gothic style shul, 2 stieblich, 1 brewery, 2 flour mills, 6 markets and 1 candle factory.”

According to tax records, in 1577 there were 28 farms in Stepan. In 1648 Stefan Czarniecki defeated the Cossacks in town.

At the beginning of the 20th century - the town of Volyn province, Rivne district.

History of the World, by Shimon Dubnov, Vol. 2, page 260, writes: “In 1386, communities existed in the area so one could infer that Jews lived in the Stepan area then. The Turks ruled Crimea. Crimean Jews traded with Jews of Volhynia and some Jews from Crimea moved into Stepan in the 1500's”

Geographical Dictionary for Kingdom of Poland and Other Slavic Kingdoms, Warsaw, 1890, pages 326-327, writes: “In 1890, there were 3,384 people in Stepan, 47% Jewish, 512 households, 3 churches, 1 Gothic style shul, 2 stieblich, 1 brewery, 2 flour mills, 6 markets and 1 candle factory.”

According to tax records, in 1577 there were 28 farms in Stepan. In 1648 Stefan Czarniecki defeated the Cossacks in town.

On the eve of the Holocaust, about 1300 Jews lived in Stepan, which amounted to about a third of the local population. After the occupation of the village by the Germans, the Jews were mobilized for forced labor, and in October 1941 a ghetto was created in the village. About 3,000 Jews from the village and surrounding villages were enclosed in the ghetto.

On the eve of the liquidation of the ghetto, in August 1942, about 500 Jews fled from it, but most of them were caught and returned to the ghetto. On August 25, 1942, the inhabitants of the ghetto were killed near Kostopol.

On the eve of the liquidation of the ghetto, in August 1942, about 500 Jews fled from it, but most of them were caught and returned to the ghetto. On August 25, 1942, the inhabitants of the ghetto were killed near Kostopol.

In 1765, 1138 Jews lived in Stepan and surrounding villages;

in 1847 - 1717 Jews in Stepan;

in 1897, there were 5,137 people in the township, of whom 1,854 were Jews.

From 1795 to 1918, Poland was chopped up and Stepan became part of Russia. Then Stepan became part of the Ukraine in 1918. In 1921 it became part of Poland until 1939. From the 13th–20th centuries, Jews lived in Stepan. Jews suffered under many attacks. However, there were signs that local Ukrainians tried to defend the Jews.

In 1913, Jews owned all 3 pharmacies, kerosene warehouse, all 69 shops (but with the exception of meat trade shops).

in 1847 - 1717 Jews in Stepan;

in 1897, there were 5,137 people in the township, of whom 1,854 were Jews.

From 1795 to 1918, Poland was chopped up and Stepan became part of Russia. Then Stepan became part of the Ukraine in 1918. In 1921 it became part of Poland until 1939. From the 13th–20th centuries, Jews lived in Stepan. Jews suffered under many attacks. However, there were signs that local Ukrainians tried to defend the Jews.

In 1913, Jews owned all 3 pharmacies, kerosene warehouse, all 69 shops (but with the exception of meat trade shops).

|

|

|

| Jewish cemetery in Stepan, 2019 | Memorial sign with the names of famous rabbis buried in this cemetery | Most famous of them was rabbi David ben Shmuel, student of Baal Shem Tov |

|

|

| Monument to the victims of the Holocaust in the cemetery in Stepan | Memorial sign to the victims of the Holocaust in Stepan in the cemetery in Holon, Israel |

Great synagogue in Stepan

by J. Peri, 1977

The great synagogue was the central structure of the town. It was built on the foundation of the ancient fortress from the period of the Polish king Stefan Boturi.

Before the entrance to the great synagogue was the “polish”. It was used as a room that allowed secular conversation among the congregants. In the entrance to the “polish” was two thick, rusty iron gates that were not being used in our time. Apparently they were used in the past to serve the defense needs in case of trouble. When the people of the town assembled in the synagogue, these heavy gates were closed and locked for the defense before the rioters who penetrated or expected to penetrate the town and the synagogue itself. Also, there was a thick wooden door with thick colorful glass panes. From the main opening, spacious steps led to within the synagogue.

From the center of the synagogue was a high platform that was used for reading the Torah and for sermons and people went up on it by steps on two sides. The ceiling of the synagogue was concave and spread out onto thick iron tracks were bowls, and a portion of them were engraved with dates, like 1635. There were thick iron chains and on the ends hung heavy copper chandeliers for the insertion of candles. On the last two chandeliers the electricity for the synagogue was connected. The hall was spacious and many of the windows had colored glass. The Ark (Aron Kodesh) was along the central wall and steps led up to it in the middle.

The Ark was carved in the thick wall. The walls of the synagogue were several meters thick. The Ark was very beautifully molded: there were two tablets of the commandments, along side were two gold-plated lions, and there were columns.

The architecture of the Ark was performed many years ago by artistic experts who were brought from outside the area or from a nearby town. Serving as the chazan was Rabbi Levi Kreezer, of blessed memory, who had a pleasant, beloved voice.

Apparently in a much later period, additional synagogues were built around the great synagogue. The upper and lower synagogues for women bordered on the common wall with the great synagogue. In this wall were built many arched openings and through these openings penetrated the voice of the chazan of the great synagogue, and thus the women were able to follow his prayers. Devorah Brunner served as gabbai of the women's synagogues.

Along side the “polish” of the great synagogue was a small synagogue for the working people – shoemakers, tailors, carpenters and others. And also there was an additional room that was used as a storeroom for scrolls, prayer books, prayer shawls (tallit), and used phylacteries (tefillin). We, the children, saw it as sort of a storeroom for hiding places that existed during the time of Rabbi Yokel the old shamash (beadle), who served like a general shamash for all the synagogues. He was very old and white and he had great strength in his arms, despite his extreme age. He would go around with his large bound keys and he would worry about the arrangement of things, the cleanness, the candles, the heat and other things. We, the children of the street, never volunteered to help Rabbi Yokel, of blessed memory, with transferring the benches and such, except on the condition that he would give up his habit of pinching us (out of affection, of course, but it caused great pain).

From the second side of the great synagogue was the “supreme” synagogue – there would pray big shots (business people), from the followers of the religious judge, Rabbi Ben-Zion Volinsky, of blessed memory. From under this synagogue was a small synagogue that was used for praying by big shots, a portion of them were from the Chassidim of the religious judge, Rabbi Pinchas “the good natured” and a portion of them of Rabbi Ben-Zion the religious judge. Attached to this synagogue was another synagogue for women of these big shots.

Before the entrance to each of these synagogue was the “polish” (the same spacious room that was used for secular conversations and for rest).

by J. Peri, 1977

The great synagogue was the central structure of the town. It was built on the foundation of the ancient fortress from the period of the Polish king Stefan Boturi.

Before the entrance to the great synagogue was the “polish”. It was used as a room that allowed secular conversation among the congregants. In the entrance to the “polish” was two thick, rusty iron gates that were not being used in our time. Apparently they were used in the past to serve the defense needs in case of trouble. When the people of the town assembled in the synagogue, these heavy gates were closed and locked for the defense before the rioters who penetrated or expected to penetrate the town and the synagogue itself. Also, there was a thick wooden door with thick colorful glass panes. From the main opening, spacious steps led to within the synagogue.

From the center of the synagogue was a high platform that was used for reading the Torah and for sermons and people went up on it by steps on two sides. The ceiling of the synagogue was concave and spread out onto thick iron tracks were bowls, and a portion of them were engraved with dates, like 1635. There were thick iron chains and on the ends hung heavy copper chandeliers for the insertion of candles. On the last two chandeliers the electricity for the synagogue was connected. The hall was spacious and many of the windows had colored glass. The Ark (Aron Kodesh) was along the central wall and steps led up to it in the middle.

The Ark was carved in the thick wall. The walls of the synagogue were several meters thick. The Ark was very beautifully molded: there were two tablets of the commandments, along side were two gold-plated lions, and there were columns.

The architecture of the Ark was performed many years ago by artistic experts who were brought from outside the area or from a nearby town. Serving as the chazan was Rabbi Levi Kreezer, of blessed memory, who had a pleasant, beloved voice.

Apparently in a much later period, additional synagogues were built around the great synagogue. The upper and lower synagogues for women bordered on the common wall with the great synagogue. In this wall were built many arched openings and through these openings penetrated the voice of the chazan of the great synagogue, and thus the women were able to follow his prayers. Devorah Brunner served as gabbai of the women's synagogues.

Along side the “polish” of the great synagogue was a small synagogue for the working people – shoemakers, tailors, carpenters and others. And also there was an additional room that was used as a storeroom for scrolls, prayer books, prayer shawls (tallit), and used phylacteries (tefillin). We, the children, saw it as sort of a storeroom for hiding places that existed during the time of Rabbi Yokel the old shamash (beadle), who served like a general shamash for all the synagogues. He was very old and white and he had great strength in his arms, despite his extreme age. He would go around with his large bound keys and he would worry about the arrangement of things, the cleanness, the candles, the heat and other things. We, the children of the street, never volunteered to help Rabbi Yokel, of blessed memory, with transferring the benches and such, except on the condition that he would give up his habit of pinching us (out of affection, of course, but it caused great pain).

From the second side of the great synagogue was the “supreme” synagogue – there would pray big shots (business people), from the followers of the religious judge, Rabbi Ben-Zion Volinsky, of blessed memory. From under this synagogue was a small synagogue that was used for praying by big shots, a portion of them were from the Chassidim of the religious judge, Rabbi Pinchas “the good natured” and a portion of them of Rabbi Ben-Zion the religious judge. Attached to this synagogue was another synagogue for women of these big shots.

Before the entrance to each of these synagogue was the “polish” (the same spacious room that was used for secular conversations and for rest).

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine