Ratne (Ratno)

Kovel district, Volyn region

Sources:

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume 5, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. Translated by Jerrold Landau, JewishGen, Inc.

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron;

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia;

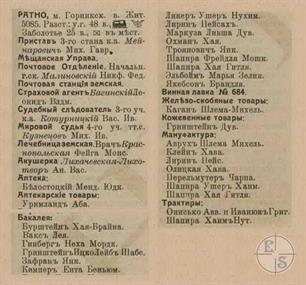

- The All South-Western Territory: reference and address book of the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Printing house L.M. Fish and P.E. Wolfson, 1913;

- Yad Vashem. Ratno

Photo:

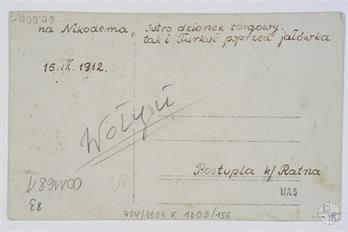

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Ratno

- David Shay, wikipedia. Ratne holocaust memorial

- Connecting Memory. Ratne - Prokhid

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume 5, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. Translated by Jerrold Landau, JewishGen, Inc.

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron;

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia;

- The All South-Western Territory: reference and address book of the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Printing house L.M. Fish and P.E. Wolfson, 1913;

- Yad Vashem. Ratno

Photo:

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Ratno

- David Shay, wikipedia. Ratne holocaust memorial

- Connecting Memory. Ratne - Prokhid

Ratno was founded approximately in XV century, during the time of the rule of the Polish dukes of the Sangoszko dynasty. The city is located on fields that today belong to the Russian Church, next to the Vizhovka River. During the war between Poland and Sweden in the years 1706-1707, the city was destroyed and its residents were killed. The survivors who succeeded in escaping returned and rebuilt Ratno. At that time, the old cemetery was built, where all of those killed during the war were buried in a mass grave. A small hill on the eastern side of the old cemetery is the only remnant of this mass grave. The few residents of the old city who survived included Reb Yaakov Ratner, who was known as a Tzadik. Nothing remains in writing about him, and we know only what our parents told us about him. The writer of these lines once saw in “Raskin's Table” one line that said, “Reb Yaakov of Ratno died in Krakow in the year...,” however, I do not recall the year listed as his year of death.

The leaders of the new city included some residents of the old city who remained alive after the aforementioned war, including the honorable and important Reb Chaim Mechenivker and his son Hirsch. Thanks to their efforts and money, the old synagogue was erected at that time, at the same time as the Catholic monastery in 1784, with the assistance and supervision of the regional governor (wojewodzina) Sosnowska, who then ruled over Ratno and its region through the authority of the government of Poland. After her death, she was buried in the bounds of the monastery, as was later on her daughter. Both of their graves can be found to this day in that monastery.

Reb Leib Sarah's, the mystic, sat and learned in the attic of the Beis Midrash for a long time. Reb Chaim Mechenivker and his son were known for their generosity and dedication to communal affairs. As is told, Reb Tzvi (Hirsch), Chaim's son, had seven sons and one daughter, whereas his younger son, Pinchas Pulmer, had seven daughters and one son.

The well-known Avrech family later stemmed from them and spread out throughout many cities in Poland and Russia. They were given the family name “Avrech” during the time of the “First Russian Revision” which was a type of census of all the Jews of Russia and Poland, for before this “Revision,” all of the Jews were considered to have disappeared. Then it became the fortune of Yossel the son-in-law of Reb Tzvi Mechenivker to be called by the name Avrech, in accordance with the verse “and they called before him Avrech”, which referred to the Righteous Joseph. This name then became the family name of his many descendants, including many Hassidic and Misnagdic Jews, rich and poor, maskilim and Torah scholars, as is found in any family.

Members of the aforementioned Mechenivker family brought as a teacher to their children someone who later became known as the “Maggid of Ratno,” Reb Tzvi the son of Reb Dov, who lived in their courtyard in Mechenivka next to the village of Buzaky, 20 kilometers from Ratno. He taught Torah to their children. This teacher was immersed day and night in the service of G-d. The elders of the city tell about a wondrous deed of his that took place during his first years of service. A woman in Mechenivka had difficulty in giving birth. Her situation was very serious and everyone gave up on her life. It was only when this teacher prayed for her with great devotion after immersing in the mikva that she gave birth in peace.

An awesome story is told from the later years of the life of the Maggid of Ratno. It took place in the Beis Midrash on Simchat Torah during the “Atah Hareita” prayer before the Hakafa (Torah circuits). The author does not recall exactly what took place, but this was certainly a wondrous deed, for he became known as a “worker of wonders,” and was given the title “The Maggid of Ratno.”

The Maggid did not have his own Hassidim, as was the custom of Tzadikim, but this writer of these lines heard from an elder Hassid of Kobrin that Rabbi Moshe of Kobrin would often mention the Maggid of Ratno and even bring down things in his name or tell stories about him. Apparently, both of them belonged to the same group, and used to travel together to the holy Rabbi Shlomo of Ludmir. To this day, various customs of the Maggid are followed in Ratno, such as the recitation of “Barchu” at the end of the Sabbath evening service, and other customs that stemmed from the Hassidim of Karlin. It is known that during his youth, the Maggid saw the Baal Shem Tov himself in the city of Brody, but due to the crowds, he only succeeded in seeing his back but not his face.

The Maggid had no sons. He married off his daughters to Ratno householders. To this day, there are Jews of Ratno who boast of being descendants of the Maggid of Ratno, including: Reb Meir Karsh who was known as Reb Meir Birker, Yisrael-Lipa Bergel, David Greenstein, and others.

The Maggid died on the 9th of Nissan 5578 (1818) and is buried in the old cemetery. Masses of people stream to his grave to this day. The graves of honorable Ratno natives, with fine pedigree and character, can be found next to his burial canopy. Many Jews, both men and women, come to visit his grave during the month of Elul, to pray and to place notes of petition.

The leaders of the new city included some residents of the old city who remained alive after the aforementioned war, including the honorable and important Reb Chaim Mechenivker and his son Hirsch. Thanks to their efforts and money, the old synagogue was erected at that time, at the same time as the Catholic monastery in 1784, with the assistance and supervision of the regional governor (wojewodzina) Sosnowska, who then ruled over Ratno and its region through the authority of the government of Poland. After her death, she was buried in the bounds of the monastery, as was later on her daughter. Both of their graves can be found to this day in that monastery.

Reb Leib Sarah's, the mystic, sat and learned in the attic of the Beis Midrash for a long time. Reb Chaim Mechenivker and his son were known for their generosity and dedication to communal affairs. As is told, Reb Tzvi (Hirsch), Chaim's son, had seven sons and one daughter, whereas his younger son, Pinchas Pulmer, had seven daughters and one son.

The well-known Avrech family later stemmed from them and spread out throughout many cities in Poland and Russia. They were given the family name “Avrech” during the time of the “First Russian Revision” which was a type of census of all the Jews of Russia and Poland, for before this “Revision,” all of the Jews were considered to have disappeared. Then it became the fortune of Yossel the son-in-law of Reb Tzvi Mechenivker to be called by the name Avrech, in accordance with the verse “and they called before him Avrech”, which referred to the Righteous Joseph. This name then became the family name of his many descendants, including many Hassidic and Misnagdic Jews, rich and poor, maskilim and Torah scholars, as is found in any family.

Members of the aforementioned Mechenivker family brought as a teacher to their children someone who later became known as the “Maggid of Ratno,” Reb Tzvi the son of Reb Dov, who lived in their courtyard in Mechenivka next to the village of Buzaky, 20 kilometers from Ratno. He taught Torah to their children. This teacher was immersed day and night in the service of G-d. The elders of the city tell about a wondrous deed of his that took place during his first years of service. A woman in Mechenivka had difficulty in giving birth. Her situation was very serious and everyone gave up on her life. It was only when this teacher prayed for her with great devotion after immersing in the mikva that she gave birth in peace.

An awesome story is told from the later years of the life of the Maggid of Ratno. It took place in the Beis Midrash on Simchat Torah during the “Atah Hareita” prayer before the Hakafa (Torah circuits). The author does not recall exactly what took place, but this was certainly a wondrous deed, for he became known as a “worker of wonders,” and was given the title “The Maggid of Ratno.”

The Maggid did not have his own Hassidim, as was the custom of Tzadikim, but this writer of these lines heard from an elder Hassid of Kobrin that Rabbi Moshe of Kobrin would often mention the Maggid of Ratno and even bring down things in his name or tell stories about him. Apparently, both of them belonged to the same group, and used to travel together to the holy Rabbi Shlomo of Ludmir. To this day, various customs of the Maggid are followed in Ratno, such as the recitation of “Barchu” at the end of the Sabbath evening service, and other customs that stemmed from the Hassidim of Karlin. It is known that during his youth, the Maggid saw the Baal Shem Tov himself in the city of Brody, but due to the crowds, he only succeeded in seeing his back but not his face.

The Maggid had no sons. He married off his daughters to Ratno householders. To this day, there are Jews of Ratno who boast of being descendants of the Maggid of Ratno, including: Reb Meir Karsh who was known as Reb Meir Birker, Yisrael-Lipa Bergel, David Greenstein, and others.

The Maggid died on the 9th of Nissan 5578 (1818) and is buried in the old cemetery. Masses of people stream to his grave to this day. The graves of honorable Ratno natives, with fine pedigree and character, can be found next to his burial canopy. Many Jews, both men and women, come to visit his grave during the month of Elul, to pray and to place notes of petition.

After the death of the holy Rabbi Yaakov-Aryeh, who was known as the Kabbalistic Rabbi (Harav Hamekubal), Rabbi Yitzchak of Niskiz ascended the rabbinical seat of Ratno. During the time of his rabbinate, no Jew of Ratno attempted to do anything without receiving the advice or consent of the rabbi, whether in matters of business, marriage matches, or civic affairs. They regarded him as a “seer” who was able to see distant things, and many wondrous deeds were attributed to him. It came to the point that it was accepted within the community that if anyone was so brazen as to do something against the will of Rabbi of Niskiz, he would not live out his year. Let those who believe - believe.

It is told that he had a pleasant appearance and he became known throughout the Jewish Diaspora. During his later years, many rabbis and Tzadikim from all over Poland came to him. Ratno was his crowning city. He would live in Ratno for several weeks a year. He had a home in Ratno and his own mikva (ritual bath) in the yard of the Trisk Shtibel. For a long time, people believed that this was the mikva of the holy Rabbi Yaakov of Ratno, and barren women from various places would come to immerse in that mikva. Only later did it become known that this was not the place of the mikva of the Maggid of Ratno, and that the Rabbi of Niskiz authorized it.

The rabbi's last trip to Ratno took place in the year 5623 (1863), five years before his death. It seems that Ratno was very dear to him, and the householders received him with great honor. Among the stories told about him, it was said that householders from Ratno and Kamin-Kashirsk entered his court in Niskiz one Sabbath. Those from Kamin-Kashirsk were brought to a table with wine in bottles, whereas those from Ratno were served wine in clay pitchers. The rabbi said, “The war of Ratno is better to me than the peace of Kamin.” (The joke being that “krieg” in Yiddish means both “war” and “pitcher,” and with the word, “shalom” (peace) he referred to one of the honorable people of Kamin-Kashirsk whose name was Shalom.) Others said that when he was asked from time to time about his dispute with the Maggid of Trisk, he answered that this dispute is an omen for a long life...

The name of the Rabbi of Niskiz is inscribed at the top of the ledger of the Chevra Shas (Talmud Study Organization) of Ratno, for in the year 5609 (1849) peace prevailed between the two organizations that preceded it. This ledger is found in Ratno to this day, and it contains the signature of the Rabbi of Niskiz. In the introduction to the ledger, he wrote in his own handwriting that he is a member of “this and what comes after.”

He died in Niskiz on the 20th of Shvat in the year 5628 (1868) at the age of 75, or some say, at the age of 80. After his death, his book “Toldot Yitzchak” was published. It is a Torah commentary in Kabbalistic style.

On the anniversary of his death, many candles are lit in Ratno and a banquet takes place. Some people own small books of Psalms, which people say, were sold by the Rabbi of Niskiz himself. Such a small book of Psalms are hard to find, and the person who owns it would protect it as the apple of his eye, and would not part with it for all the money in the world.

by Fishel Held

It is told that he had a pleasant appearance and he became known throughout the Jewish Diaspora. During his later years, many rabbis and Tzadikim from all over Poland came to him. Ratno was his crowning city. He would live in Ratno for several weeks a year. He had a home in Ratno and his own mikva (ritual bath) in the yard of the Trisk Shtibel. For a long time, people believed that this was the mikva of the holy Rabbi Yaakov of Ratno, and barren women from various places would come to immerse in that mikva. Only later did it become known that this was not the place of the mikva of the Maggid of Ratno, and that the Rabbi of Niskiz authorized it.

The rabbi's last trip to Ratno took place in the year 5623 (1863), five years before his death. It seems that Ratno was very dear to him, and the householders received him with great honor. Among the stories told about him, it was said that householders from Ratno and Kamin-Kashirsk entered his court in Niskiz one Sabbath. Those from Kamin-Kashirsk were brought to a table with wine in bottles, whereas those from Ratno were served wine in clay pitchers. The rabbi said, “The war of Ratno is better to me than the peace of Kamin.” (The joke being that “krieg” in Yiddish means both “war” and “pitcher,” and with the word, “shalom” (peace) he referred to one of the honorable people of Kamin-Kashirsk whose name was Shalom.) Others said that when he was asked from time to time about his dispute with the Maggid of Trisk, he answered that this dispute is an omen for a long life...

The name of the Rabbi of Niskiz is inscribed at the top of the ledger of the Chevra Shas (Talmud Study Organization) of Ratno, for in the year 5609 (1849) peace prevailed between the two organizations that preceded it. This ledger is found in Ratno to this day, and it contains the signature of the Rabbi of Niskiz. In the introduction to the ledger, he wrote in his own handwriting that he is a member of “this and what comes after.”

He died in Niskiz on the 20th of Shvat in the year 5628 (1868) at the age of 75, or some say, at the age of 80. After his death, his book “Toldot Yitzchak” was published. It is a Torah commentary in Kabbalistic style.

On the anniversary of his death, many candles are lit in Ratno and a banquet takes place. Some people own small books of Psalms, which people say, were sold by the Rabbi of Niskiz himself. Such a small book of Psalms are hard to find, and the person who owns it would protect it as the apple of his eye, and would not part with it for all the money in the world.

by Fishel Held

By 1897, the local Jewish population had reached 2,219 (71,8% of the total population). Neskhizh Hasids were present in the city, and by the early 20th century, Zionist movements were becoming active.

WWI led to a halving of the local Jewish population to 1,554 (64,3% of the total population) in 1921.

In 1912, a school was opened with teaching in Hebrew.

In 1914, Jews belonged to the only pharmacy, the only warehouse of pharmacy goods, a tavern, 24 shops (including all 15 grocery, all 7 manufactory).

A Jewish woman Feiga Krasnopolska worked as a doctor in the township’s hospital.

In 1920, during the pogrom arranged by the detachments of S.N. Bulak-Balakhovich, 3 Jews were killed.

In the 1920-30s, different Jewish political parties (e.g., the Bund, HaMizrahi) and especially the Zionist youth movements (Hashomer Hatzair and Hehalutz) became active in the town.

In the 1920s, 8 of the 12 members of the local council were Jews.

In 1923, the Jewish Bank was opened.

In 1926, the school of Tarbut network began to work.

By 1937, the Jewish population had grown to 2,140.

WWI led to a halving of the local Jewish population to 1,554 (64,3% of the total population) in 1921.

In 1912, a school was opened with teaching in Hebrew.

In 1914, Jews belonged to the only pharmacy, the only warehouse of pharmacy goods, a tavern, 24 shops (including all 15 grocery, all 7 manufactory).

A Jewish woman Feiga Krasnopolska worked as a doctor in the township’s hospital.

In 1920, during the pogrom arranged by the detachments of S.N. Bulak-Balakhovich, 3 Jews were killed.

In the 1920-30s, different Jewish political parties (e.g., the Bund, HaMizrahi) and especially the Zionist youth movements (Hashomer Hatzair and Hehalutz) became active in the town.

In the 1920s, 8 of the 12 members of the local council were Jews.

In 1923, the Jewish Bank was opened.

In 1926, the school of Tarbut network began to work.

By 1937, the Jewish population had grown to 2,140.

In September 1939, with the arrival of the Red Army in the town following the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, Ratno became part of Soviet Ukraine. Under the Soviets private enterprise was banned and all political organizations, except the Communist Party, were closed down. The Tarbut school was also shut down.

The Germans captured Ratno on June 28, 1941. During the first days of July Ukrainians staged two pogroms in Ratno, looting property and killing several Jews. A German unit arrived in the town to "restore order". Local Ukrainians initially mistook the Germans for armed Jews and opened fire. After killing several Ukrainians, the Germans conducted a retaliation operation. Claiming that the Jews had fired on them, the Germans killed 30 Jewish men and 30 Soviet POWs.

From July 14 the Jews had to wear a white armband (replaced later by a yellow patch) on their outer clothes - on the back and on the chest. A curfew was imposed from 5 p.m. until 6 a.m. On July 17 the Germans set up a Judenrat (Jewish council), headed by David Aharon Shapiro and a Jewish police force. The German authorities confiscated all the livestock of the Jews and, later, took most of their valuables, furniture, and clothes.

The Judenrat mobilized local Jews for different kinds of forced labor. In November 1941 workshops were set up in the town for skilled workers. In June 1942 there was a partisan raid on Ratno in which two German agricultural leaders (Sonderfuhrer) were killed. The SS retaliated by murdering 120 Jews on the outskirts of the town. Apparently in late July or early August, several Jews were murdered near the Cziplik Tract.

On August 25 or 26, over 1,000 Jews were shot to death at Prochуd Hill outside the town by German units, assisted by Ukrainian auxiliary police. Shortly afterwards, Jews who had been caught in hiding were shot to death at the old cemetery in the town. About several dozen surviving Jewish artisans continued to work for the Germans in workshops. By early 1943, those artisans had been shot to death as well.

The Germans captured Ratno on June 28, 1941. During the first days of July Ukrainians staged two pogroms in Ratno, looting property and killing several Jews. A German unit arrived in the town to "restore order". Local Ukrainians initially mistook the Germans for armed Jews and opened fire. After killing several Ukrainians, the Germans conducted a retaliation operation. Claiming that the Jews had fired on them, the Germans killed 30 Jewish men and 30 Soviet POWs.

From July 14 the Jews had to wear a white armband (replaced later by a yellow patch) on their outer clothes - on the back and on the chest. A curfew was imposed from 5 p.m. until 6 a.m. On July 17 the Germans set up a Judenrat (Jewish council), headed by David Aharon Shapiro and a Jewish police force. The German authorities confiscated all the livestock of the Jews and, later, took most of their valuables, furniture, and clothes.

The Judenrat mobilized local Jews for different kinds of forced labor. In November 1941 workshops were set up in the town for skilled workers. In June 1942 there was a partisan raid on Ratno in which two German agricultural leaders (Sonderfuhrer) were killed. The SS retaliated by murdering 120 Jews on the outskirts of the town. Apparently in late July or early August, several Jews were murdered near the Cziplik Tract.

On August 25 or 26, over 1,000 Jews were shot to death at Prochуd Hill outside the town by German units, assisted by Ukrainian auxiliary police. Shortly afterwards, Jews who had been caught in hiding were shot to death at the old cemetery in the town. About several dozen surviving Jewish artisans continued to work for the Germans in workshops. By early 1943, those artisans had been shot to death as well.

In 2014, within the framework of the “Protecting Memory” project and with funds provided by the German Federal Foreign Office, a memorial complex designed by the Ukrainian architect Taras Savka was built at the site of the shooting of 1,500 Jews from the Ratne ghetto near the village of Prokhid.

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate