Rafalivka

Varash district, Rivne region

Rafalivka is urban-type settlement (since 1957) in the Varash district of the Rivne region. It was founded in 1902 as the township of New Rafalovka near the railway stations in the Lutsk district of the Volyn province. In 1919–39 - in the Volyn Voivodeship as part of Poland, in 1939–91 - as part of the Ukrainian SSR.

In 1910, about 50 Jews lived in Rafalivka,

in 1921 - 332 (51.4%),

in 1931 - approx. 400 Jews.

During the interwar period, about 600 Jews lived in Rafalivka, accounting for approximately one-third of the townlet’s population. Some were petty merchants and artisans, a number owned a sawmill, and still others were wholesalers. The community boasted a savings-and-loan association, a Tarbut school that taught in Hebrew, a cultural center, and chapters of Zionist parties.

During the era of Soviet rule that began in September 1939, many Jewish refugees from central and western Poland settled in Rafalivka.

In July 1941, robberies and beatings of Jews arranged by local residents took place in Rafalivka.

The Germans entered Rafalivka in late July 1941. They forced the Jews to remit ransoms and set up a Judenrat, which included representatives from two nearby Jewish farming hamlets, Olizarka and Zholudsk.

The Rafalivka ghetto was established on May 1, 1942. Jews from Olizarka, Zholudsk, and villages in the vicinity were brought in, raising its population to approximately 2,500.

In July 1942, sixty Jewish forced laborers were murdered outside of the town.

On August 29, 1942, the Rafalowka ghetto was liquidated, and 2,250 Jews were taken to pits on the road to Suchowola, where they were murdered. Dozens escaped to forests and villages, where Polish peasants and Ukrainian Baptists assisted them. Some young people formed fighting units and later joined the Soviet partisan detachment of A.P. Brinsky.

About thirty of Rafalivka’s Jews survived.

In 1910, about 50 Jews lived in Rafalivka,

in 1921 - 332 (51.4%),

in 1931 - approx. 400 Jews.

During the interwar period, about 600 Jews lived in Rafalivka, accounting for approximately one-third of the townlet’s population. Some were petty merchants and artisans, a number owned a sawmill, and still others were wholesalers. The community boasted a savings-and-loan association, a Tarbut school that taught in Hebrew, a cultural center, and chapters of Zionist parties.

During the era of Soviet rule that began in September 1939, many Jewish refugees from central and western Poland settled in Rafalivka.

In July 1941, robberies and beatings of Jews arranged by local residents took place in Rafalivka.

The Germans entered Rafalivka in late July 1941. They forced the Jews to remit ransoms and set up a Judenrat, which included representatives from two nearby Jewish farming hamlets, Olizarka and Zholudsk.

The Rafalivka ghetto was established on May 1, 1942. Jews from Olizarka, Zholudsk, and villages in the vicinity were brought in, raising its population to approximately 2,500.

In July 1942, sixty Jewish forced laborers were murdered outside of the town.

On August 29, 1942, the Rafalowka ghetto was liquidated, and 2,250 Jews were taken to pits on the road to Suchowola, where they were murdered. Dozens escaped to forests and villages, where Polish peasants and Ukrainian Baptists assisted them. Some young people formed fighting units and later joined the Soviet partisan detachment of A.P. Brinsky.

About thirty of Rafalivka’s Jews survived.

The description of the town of Rafalovka, which I'm bringing to you here, is 66 years old, a few years before the beginning of World War I. When I write Rafalovka, I don't add 'Old' as it was later known, because at the time there was only one Rafalovka. Jewish Rafalovka was located at the center of town surrounded on three sides by goy neighborhoods and on the west by the Styr River.

The Jews owned about 150 houses, some small, some large, 170 families lived there. There were families that didn't have their own home and they would rent rooms from Jewish homeowners. Jews settled in the town hundreds of years ago. One day a notebook of the Hevre Kadisha was discovered in Rafalovka dating 325 years earlier. I saw it with my own eyes but couldn't decipher all the entries because ink stains covered most pages.

Jews worked in cattle trade and wood and were shopkeepers, shoemakers and tailors.

Two flourmills operated by the Styr River. One was called Torkevits Mill and the other was called the Community Mill, the hromada. This mill had a ferry that used to go back and forth on the river. The Torkenitch mill was on the southern side of town, in an area called “Polsha.” The Community mill was on the northern side of the river, near the village of Babka.

The Torkenitch mill was leased to a Jewish family who ran it. The second mill belonged to a Jew, and Meir Vollich Kommissar!, a wealthy man. He had a stone house – only rich men lived in such a house at that time – and he rented the ferry out to another Jew named Leibel Forumtshik (Leibel who operates the ferry), the grandfather of Yaakov Sarid Schnieder.

The ferry worked after Passover and sometimes earlier when the ice just began to melt. Leibel would hire peasants who would carry the ferry on large boats. People, animals and goods would be moved back and forth on the overflowing river. When the water level went down the ferry would be put near a fence and be moved back and forth across the river by a rope. There was a straw hut on the ferry to protect people from the rain.

The Jews owned about 150 houses, some small, some large, 170 families lived there. There were families that didn't have their own home and they would rent rooms from Jewish homeowners. Jews settled in the town hundreds of years ago. One day a notebook of the Hevre Kadisha was discovered in Rafalovka dating 325 years earlier. I saw it with my own eyes but couldn't decipher all the entries because ink stains covered most pages.

Jews worked in cattle trade and wood and were shopkeepers, shoemakers and tailors.

Two flourmills operated by the Styr River. One was called Torkevits Mill and the other was called the Community Mill, the hromada. This mill had a ferry that used to go back and forth on the river. The Torkenitch mill was on the southern side of town, in an area called “Polsha.” The Community mill was on the northern side of the river, near the village of Babka.

The Torkenitch mill was leased to a Jewish family who ran it. The second mill belonged to a Jew, and Meir Vollich Kommissar!, a wealthy man. He had a stone house – only rich men lived in such a house at that time – and he rented the ferry out to another Jew named Leibel Forumtshik (Leibel who operates the ferry), the grandfather of Yaakov Sarid Schnieder.

The ferry worked after Passover and sometimes earlier when the ice just began to melt. Leibel would hire peasants who would carry the ferry on large boats. People, animals and goods would be moved back and forth on the overflowing river. When the water level went down the ferry would be put near a fence and be moved back and forth across the river by a rope. There was a straw hut on the ferry to protect people from the rain.

There were two groups of Hassids: the Hassids of the Rabbi from Lyubeshov and the Hassids of the Rabbi of Stepan. They vehemently disagreed and sometimes they went snitching to the authorities and set fire to property. For instance, a house was once set on fire near the Lyubeshov synagogue with clear intention to burn it down. This was the work of the Hassids of the Rabbi from Stepan who were known to be extremists. But that day there was a strong wind blowing in the opposite direction, and more than half the town's houses were burned down, including the synagogue of those who set the fire. In the end it was the Lyubeshov synagogue that survived the fire intact, and many saw this as the intervention of God.

Ruins of an old destroyed synagogue stood behind the Provoslav church on the river near the town's bathhouse. When young couples married, the bride and groom would be taken there with the whole wedding party because people believed it was a holy place that brought luck and prosperity.

There were two religious judges in town, one for each group of Hassids. They made their living by selling yeast and candles for Sabbath, as was customary in many communities in those days. Sometimes they would hold a Torah court between two rivals.

People began rebuilding the houses in the town after the big fire. At that time they also started building New Rafalovka, i.e. Rafalovka the Station near the train tracks. I remember how David Koifman began rebuilding his house in the town and then stopped building and moved to New Rafalovka. At that time there were very few homes in New Rafalovka. Benjamin Gildengoren also moved to New Rafalovka.

It should be said that the Jews of Old Rafalovka were considered at the time to be the most educated people in the area. The Vladimirets Jews were called “di smolyares” meaning “the people who work with pitch,” because they produced tar.

There were kleyzmers in Rafalovka who traveled throughout the area to play at weddings. They reached as far as Sarny in the east and worked in Vladimirets, Berezhnitsa, and all the way south to Stepan on the way to Rovno. The Jews also had saloons where they sold wine to the goyim and cooked fish meals for them. State laws ordered Jews to close the saloons and food places on the Christian holidays. The Jews would bribe the oridanik (governmental clerk) and the strarjnick (policeman) to close their eyes to the open restaurants and allow the owners to make a living. In the winter fairs were held in the forest and many times forest merchants would come from Pinsk for a share in the business. There were also peddlers who carried their merchandise on their backs and went around the villages exchanging their goods for agricultural produce. All town residents were terribly poor and they would all beg.

by Moshe Appelboim, Memories from Rafalovka

Ruins of an old destroyed synagogue stood behind the Provoslav church on the river near the town's bathhouse. When young couples married, the bride and groom would be taken there with the whole wedding party because people believed it was a holy place that brought luck and prosperity.

There were two religious judges in town, one for each group of Hassids. They made their living by selling yeast and candles for Sabbath, as was customary in many communities in those days. Sometimes they would hold a Torah court between two rivals.

People began rebuilding the houses in the town after the big fire. At that time they also started building New Rafalovka, i.e. Rafalovka the Station near the train tracks. I remember how David Koifman began rebuilding his house in the town and then stopped building and moved to New Rafalovka. At that time there were very few homes in New Rafalovka. Benjamin Gildengoren also moved to New Rafalovka.

It should be said that the Jews of Old Rafalovka were considered at the time to be the most educated people in the area. The Vladimirets Jews were called “di smolyares” meaning “the people who work with pitch,” because they produced tar.

There were kleyzmers in Rafalovka who traveled throughout the area to play at weddings. They reached as far as Sarny in the east and worked in Vladimirets, Berezhnitsa, and all the way south to Stepan on the way to Rovno. The Jews also had saloons where they sold wine to the goyim and cooked fish meals for them. State laws ordered Jews to close the saloons and food places on the Christian holidays. The Jews would bribe the oridanik (governmental clerk) and the strarjnick (policeman) to close their eyes to the open restaurants and allow the owners to make a living. In the winter fairs were held in the forest and many times forest merchants would come from Pinsk for a share in the business. There were also peddlers who carried their merchandise on their backs and went around the villages exchanging their goods for agricultural produce. All town residents were terribly poor and they would all beg.

by Moshe Appelboim, Memories from Rafalovka

Sources:

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron;

- Moshe Appelboim, Memories from Rafalovka. Memorial book for the towns of Old Rafalowka, New Rafalowka, Olizarka, Zoludzk and vicinity. Edited by Pinhas and Malkah Hagin, Tel Aviv, 1996. Translated by Rachel Zetland, JewishGen, Inc.

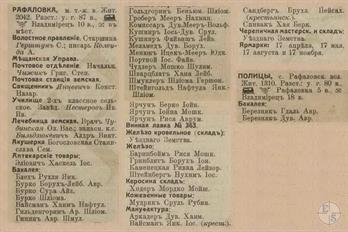

- The All South-Western Territory: reference and address book of the Kyiv, Podolsk and Volyn provinces. Printing house L.M. Fish and P.E. Wolfson, 1913;

- Yad Vashem. Rafalowka: Historical Background during the Holocaust

Photo:

- European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Rafalivka Jewish Cemetery

- European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. New Jewish cemetery in Stara Rafalivka.

Published by Center for Jewish Art

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine