Ostroh

Rivne region - list of settlements and location of objects

Ostroh, 2012, 2015, 2020

Ostroh, 2012, 2015, 2020

Rivne region

Ostroh is first mentioned in Hypatian Codex in 1100 as the possession of Prince David Igorevich.

With the name of the first historically known prince of the Ostrog dynasty - Danila (died around 1386), they associate the construction of the oldest in the town tower in the 3rd quarter of the XIV century -Donzhon of the Ostrog castle.

In 1576, Prince Vasily-Konstantin Ostrozhsky founded the first higher educational institution in Eastern Europe - the Greco-Slavic-Latin Academy (Ostrog Academy), and in 1577 the printing house was founded with Ivan Fedorov. Ivan Fedorov moves to Ostrog, where he prints the “Primer”, and in 1581 - the first Bible by the Church Slavonic language (Ostrozhskaya Bible).

In 1795, Ostrog receives the status of the city.

With the name of the first historically known prince of the Ostrog dynasty - Danila (died around 1386), they associate the construction of the oldest in the town tower in the 3rd quarter of the XIV century -Donzhon of the Ostrog castle.

In 1576, Prince Vasily-Konstantin Ostrozhsky founded the first higher educational institution in Eastern Europe - the Greco-Slavic-Latin Academy (Ostrog Academy), and in 1577 the printing house was founded with Ivan Fedorov. Ivan Fedorov moves to Ostrog, where he prints the “Primer”, and in 1581 - the first Bible by the Church Slavonic language (Ostrozhskaya Bible).

In 1795, Ostrog receives the status of the city.

Jews, apparently, settled in Ostroh in the 1st half of the 15th century. The earliest Jewish burials dates back to 1445

Documentary certificates of Jews in OstroH date back to 1495. The decree on the exile of Jews from Lithuania also touched the Jews of Ostroh, but in 1503 they were allowed to return. In 1536, King Sigismund I issued a decision that determined taxes that Ostroh Jews were supposed to pay.

In the 16–1nd half of the 17th century, many Jews from Ostroh conducted trade with Wallachia, supplying clothes and other goods in exchange for cattle. They also exported forests, wax, potash, leather products from Poland to Danzig. Successful trade led to the rapid growth of the Jewish population of Ostroh. The community became one of the largest in Volyn and was represented in the Vaad of Four Lands.

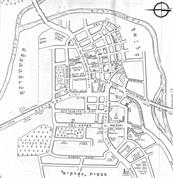

Jews lived in a special quarter - ghetto. In 1603, there were 73 Jewish houses in Ostroh, 50 of them were on Starozhydovskaya Street.

In the middle of the 16th century, a stone synagogue was built in Ostroh.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the rapid increase in the number of the Jewish population continued.

During the uprising of Khmelnitsky, the Jewish community of the city was destroyed. In 1648, 600 Jews were cut out, in February 1649 - 300. The large synagogue was turned into a stable, the houses of the Jews were destroyed, since the Cossacks and local residents were looking for treasures supposedly buried by Jews.

The Jewish community of Ostroh did not soon recover from the consequences of a terrible massacre. So, in 1660, there were only five houses belonging to the Jews in the city. But in 1666, a representative of Ostroh reappeared in the Vaad of Four Lands.

In 1678, the Diet of Poland decided to help the city “destroyed to the ground and trimmed with the ground”, confirming the privileges provided by the Polish kings to the inhabitants of Ostroh - both Christians and Jews.

Documentary certificates of Jews in OstroH date back to 1495. The decree on the exile of Jews from Lithuania also touched the Jews of Ostroh, but in 1503 they were allowed to return. In 1536, King Sigismund I issued a decision that determined taxes that Ostroh Jews were supposed to pay.

In the 16–1nd half of the 17th century, many Jews from Ostroh conducted trade with Wallachia, supplying clothes and other goods in exchange for cattle. They also exported forests, wax, potash, leather products from Poland to Danzig. Successful trade led to the rapid growth of the Jewish population of Ostroh. The community became one of the largest in Volyn and was represented in the Vaad of Four Lands.

Jews lived in a special quarter - ghetto. In 1603, there were 73 Jewish houses in Ostroh, 50 of them were on Starozhydovskaya Street.

In the middle of the 16th century, a stone synagogue was built in Ostroh.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the rapid increase in the number of the Jewish population continued.

During the uprising of Khmelnitsky, the Jewish community of the city was destroyed. In 1648, 600 Jews were cut out, in February 1649 - 300. The large synagogue was turned into a stable, the houses of the Jews were destroyed, since the Cossacks and local residents were looking for treasures supposedly buried by Jews.

The Jewish community of Ostroh did not soon recover from the consequences of a terrible massacre. So, in 1660, there were only five houses belonging to the Jews in the city. But in 1666, a representative of Ostroh reappeared in the Vaad of Four Lands.

In 1678, the Diet of Poland decided to help the city “destroyed to the ground and trimmed with the ground”, confirming the privileges provided by the Polish kings to the inhabitants of Ostroh - both Christians and Jews.

In the mid -17th century, Haidamaks tried to arrange a pogrom in Ostroh, but the Jews protected by the Tatars living in the city. For a long time, Jews of Ostroh in memory of this day read the piyuts and prayers in the Main synagogue.

The city suffered in 1792, during its siege by Russian troops. The Polish troops retreated, but the Russians considered the synagogue, in which the Ostrog Jews were hiding, like a fortress with a Polish garrison, and fired at it from guns. According to legend, the nuclei, flying inside the building through the windows, miraculously froze in the air and did not explode. On the third day of the shelling, a brave man named Elizer managed to get out of the synagogue and showed the Russian troops a trad over the Viliya River (the Poles destroyed the bridge before the retreat), after which they left Ostroh alone.

In memory of the miracle in the wall of the synagogue, traces of nuclei were not hung up, and one core was hanged inside the building on the chain. According to one version, this chain was gold. In memory of the happy deliverance in Ostroh synagogues, a description of this event was read (Megilat Tamuz).

In 1765, 1777 Jews lived in Ostroh, who owned 415 houses,

in 1784 - 1123 (323 houses),

in 1787 - 1829 (282 houses).

The city suffered in 1792, during its siege by Russian troops. The Polish troops retreated, but the Russians considered the synagogue, in which the Ostrog Jews were hiding, like a fortress with a Polish garrison, and fired at it from guns. According to legend, the nuclei, flying inside the building through the windows, miraculously froze in the air and did not explode. On the third day of the shelling, a brave man named Elizer managed to get out of the synagogue and showed the Russian troops a trad over the Viliya River (the Poles destroyed the bridge before the retreat), after which they left Ostroh alone.

In memory of the miracle in the wall of the synagogue, traces of nuclei were not hung up, and one core was hanged inside the building on the chain. According to one version, this chain was gold. In memory of the happy deliverance in Ostroh synagogues, a description of this event was read (Megilat Tamuz).

In 1765, 1777 Jews lived in Ostroh, who owned 415 houses,

in 1784 - 1123 (323 houses),

in 1787 - 1829 (282 houses).

After the outbreak of the Soviet-German war, many representatives of Jewish youth were mobilized in the Red Army. A certain number of Jews managed to flee from Ostroh.

German troops occupied the city on July 3, 1941. The Jewish population of Ostroh at that time was 9.5 thousand people.

On August 4, 1941, three thousand Jews were killed in the forests near the city, during the next campaign on September 1, 2.5 thousand more people were taken to the forest near the city of Neteshin Khmelnitsky region.

In Ostroh, Judenrat was created, who was headed by A. Comedant.

In the ghetto was Jewish underground. Having received a message that the Germans are preparing the next action, 800 Jews fled to the forests. The action took place on October 15, 1942: about three thousand people were killed in the vicinity of the city - all the Jews remaining in Ostroh.

Most of the fled died at the hands of Ukrainian peasants or detachments of Ukrainian nationalists. Those who survived managed to create several partisan detachments - under the command of H.Kaplan, M.Traiberman and P.Eisenstein.

A small number of Jews returned to Ostroh after the liberation of the city on January 13, 1944 as part of a partisan form. Soon, almost all returning left for Poland, and from there to Eretz Israel and other countries. As of 2015, several Jews lived in the city.

German troops occupied the city on July 3, 1941. The Jewish population of Ostroh at that time was 9.5 thousand people.

On August 4, 1941, three thousand Jews were killed in the forests near the city, during the next campaign on September 1, 2.5 thousand more people were taken to the forest near the city of Neteshin Khmelnitsky region.

In Ostroh, Judenrat was created, who was headed by A. Comedant.

In the ghetto was Jewish underground. Having received a message that the Germans are preparing the next action, 800 Jews fled to the forests. The action took place on October 15, 1942: about three thousand people were killed in the vicinity of the city - all the Jews remaining in Ostroh.

Most of the fled died at the hands of Ukrainian peasants or detachments of Ukrainian nationalists. Those who survived managed to create several partisan detachments - under the command of H.Kaplan, M.Traiberman and P.Eisenstein.

A small number of Jews returned to Ostroh after the liberation of the city on January 13, 1944 as part of a partisan form. Soon, almost all returning left for Poland, and from there to Eretz Israel and other countries. As of 2015, several Jews lived in the city.

Sources:

- Sefer Ostrog. Published in Tel Aviv 1987. Translated by Yocheved Klausner, JewishGen, Inc.

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- The magazine "Seven Arts". Blog of Mikhail Nosonovsky. Incredible find in the Ostroh

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

- Shimon Zaychik (1930s), Henryk Poddebski (1922). Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk

- Eugene M. Avrutin, Valerii Dymshits, Alexander Lvov, Harriet Murav and Alla Sokolova. Photographing the Jewish Nation. Pictures from S.An-sky's Ethnographic Expeditions;

- Vob, Wikipedia. Holocaust memorial in Ostroh

- Posterrr, Wikipedia. Vul. Revkomivska 2

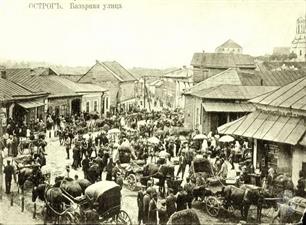

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Ostrog

- Ukrainer. Synagogue in Ostroh. Restoration of ruin

- Sefer Ostrog. Published in Tel Aviv 1987. Translated by Yocheved Klausner, JewishGen, Inc.

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- The magazine "Seven Arts". Blog of Mikhail Nosonovsky. Incredible find in the Ostroh

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

- Shimon Zaychik (1930s), Henryk Poddebski (1922). Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk

- Eugene M. Avrutin, Valerii Dymshits, Alexander Lvov, Harriet Murav and Alla Sokolova. Photographing the Jewish Nation. Pictures from S.An-sky's Ethnographic Expeditions;

- Vob, Wikipedia. Holocaust memorial in Ostroh

- Posterrr, Wikipedia. Vul. Revkomivska 2

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Ostrog

- Ukrainer. Synagogue in Ostroh. Restoration of ruin

In the city, the castle built by princes Ostrozhski is preserved, in which today the historical museum is located. There are many interesting exhibits, including associated with the Jewish past of Ostroh.

|

|

|

| Ostrozhsky castle, the postcard of the beginning of XX century | Tower of the castle | In the museum |

|

|

|

| Ceramic tiles with an inscription in Hebrew | Dishes with Hebrew inscriptions |

In 1912, Solomon Yudovin, participant of An-sky expedition, made the frostography of matseva and craftsman. This matseva has been preserved, it can be seen in a restored cemetery. Interestingly, it was identified only in 2020, by the researcher Alexandra Fischel.

Among the Great Torah Scholars who lived and worked in the town – apart from Rabbi Shmuel Eydels and Rabbi Meir Margaliot – were:

Rabbi Shlomo Lurie who lived in the XVI century, headed an important Yeshiva in Ostrog and served as an erudite Rabbi to all the Wohlin District. He moved to Lublin. His famous works included: “Hochmat Shlomo” and “Yam Shel Shlomo”.

Rabbi Yeshayahu Halevy Horovitz lived in the XVII century and served as rabbi of Ostrog. His book “Shnei Luchot Habrit” became famous throughout the world. He immigrated to Eretz Israel and lived in Jerusalem and Safed, was buried in Tiberias next to the tombs of Rabbi Yochanan Hasandlar and Rambam.

Rabbi David Segal, who wrote “Torei Zahav”, lived in the XVII century and served as President of Tribunal and Head of a Yeshiva in Ostrog. His book is a comment on Shulkhan Arukh by Rabbi Joseph Caro, who was among the survivors of the persecutions. He wrote special prayers in memory of the disaster.

Scholar Rabbi Yaacov son of Rabbi Chaim Rapoport, was President of Tribunal of Ostrog and the District.

Rabbi Shlomo Lurie who lived in the XVI century, headed an important Yeshiva in Ostrog and served as an erudite Rabbi to all the Wohlin District. He moved to Lublin. His famous works included: “Hochmat Shlomo” and “Yam Shel Shlomo”.

Rabbi Yeshayahu Halevy Horovitz lived in the XVII century and served as rabbi of Ostrog. His book “Shnei Luchot Habrit” became famous throughout the world. He immigrated to Eretz Israel and lived in Jerusalem and Safed, was buried in Tiberias next to the tombs of Rabbi Yochanan Hasandlar and Rambam.

Rabbi David Segal, who wrote “Torei Zahav”, lived in the XVII century and served as President of Tribunal and Head of a Yeshiva in Ostrog. His book is a comment on Shulkhan Arukh by Rabbi Joseph Caro, who was among the survivors of the persecutions. He wrote special prayers in memory of the disaster.

Scholar Rabbi Yaacov son of Rabbi Chaim Rapoport, was President of Tribunal of Ostrog and the District.

Since 1793, Ostroh was part of Russia.

In 1797, 133 Jewish merchants and 1624 Jews-Burghers lived in Ostroh and in the county;

in 1803 - 45 Jewish merchants, 2161 Jewish-Burghers;

in 1847 - 7300 Jews,

in 1897 - 9208 Jews.

At the end of the 19th century 3 synagogues and 19 prayer houses acted in Ostroh. In 1910, a state-owned primary Jewish school with a craft department, Talmud Tora, a private Jewish male school acted in the city.

In 1797, 133 Jewish merchants and 1624 Jews-Burghers lived in Ostroh and in the county;

in 1803 - 45 Jewish merchants, 2161 Jewish-Burghers;

in 1847 - 7300 Jews,

in 1897 - 9208 Jews.

At the end of the 19th century 3 synagogues and 19 prayer houses acted in Ostroh. In 1910, a state-owned primary Jewish school with a craft department, Talmud Tora, a private Jewish male school acted in the city.

In 1920–39 Ostroh - as part of Poland.

Public figures with a developed sense of public work were at that time Kalman Frenkeland Avigdor Kamerman who served as Deputy Mayor of Ostroh and saw to it that the Jews were not deprived by the town authorities.

Ostroh was the centre of Zionist and pioneering activities in Wohlin in the years preceding the Holocaust. Youth from all Zionist movements went to training; Jewish education developed, schools and “Tarbut” High school were founded, lectures took place on Zionist and literary subjects. The Zionist Women's Association also participated in the various activities for the building of Eretz Israel.

Notables headed the community, such as Avraham Aharon Finkelstein, Haim Galberson and Haim Davidson, who all assisted financially Rabbis and social institutions in the town. Among the town Rabbis were: Rabbi Yossef Wertheim, who moved to Horovishev and then immigrated to Eretz Israel and died in Jerusalem; he was known to be “sharp-witted and learned”, popular in Zionist circles and with the authorities; after him, as rabbi of the town, was Rabbi Mordechai Ginzburg.

The last religious judges before the Holocaust were Rabbi Ephraim Guberman, Rabbi Dov Kaplan and Rabbi Zeev Wolf Sefarad, son of the last master and teacher in the town, Rabbi Eliakim Gezel Gelman was Rabbi of the New Town. During those days, famous in the town was learned scholar, and a strong opponent to the Hassidic Movement – Rabbi Menachem Mendel Biber.

The notables who acted in the Ostroh Municipality were Shlomo Comandant, Bezalel Bramnik, Mordechai Yaacov Nordman, Grisha Band, Moshe Abelman and others. Chaim Davidson and Leibush Biber were the most prominent Zionist leaders in Ostroh.

The activities of the Zionist leaders were felt in all the areas of life.

Ostroh was also blessed with excellent teachers, having a strong public Zionist sense, such as Shmuel Sarir, about whom the late President of Israel Shazar used to speak a lot, Mordechai Kaplan, Yaacov Nordman, Moshe Tolpin, Tanchum Zebin, Josef Finkelstein and others.

People with a leadership ability appeared in all the Zionist youth movements in the town. Yankel Kaplan of Gordonia fell as an outstanding partisan behind Nazi lines.

There was also a Mishnah Society in the town, led by Rabbi Meir Zvi Finkel and Rabbi Pinchas Pelikop which had tens of notables who studied every single day of the year; at the “end” of their studies, they used to organize a feast at the home of the leader of the Society; I, as a child, used to enjoy those ceremonies at home and the fragrant dishes prepared by the cooks.

That was the golden age of the varied public activity in the town until the Holocaust which brought about the bitter end of the splendid community. After the city’s joining the Soviet Union in 1939, all Jewish institutions were closed. In the spring of 1940, many Jewish families were expelled from the city to remote areas of the Soviet Union.

Public figures with a developed sense of public work were at that time Kalman Frenkeland Avigdor Kamerman who served as Deputy Mayor of Ostroh and saw to it that the Jews were not deprived by the town authorities.

Ostroh was the centre of Zionist and pioneering activities in Wohlin in the years preceding the Holocaust. Youth from all Zionist movements went to training; Jewish education developed, schools and “Tarbut” High school were founded, lectures took place on Zionist and literary subjects. The Zionist Women's Association also participated in the various activities for the building of Eretz Israel.

Notables headed the community, such as Avraham Aharon Finkelstein, Haim Galberson and Haim Davidson, who all assisted financially Rabbis and social institutions in the town. Among the town Rabbis were: Rabbi Yossef Wertheim, who moved to Horovishev and then immigrated to Eretz Israel and died in Jerusalem; he was known to be “sharp-witted and learned”, popular in Zionist circles and with the authorities; after him, as rabbi of the town, was Rabbi Mordechai Ginzburg.

The last religious judges before the Holocaust were Rabbi Ephraim Guberman, Rabbi Dov Kaplan and Rabbi Zeev Wolf Sefarad, son of the last master and teacher in the town, Rabbi Eliakim Gezel Gelman was Rabbi of the New Town. During those days, famous in the town was learned scholar, and a strong opponent to the Hassidic Movement – Rabbi Menachem Mendel Biber.

The notables who acted in the Ostroh Municipality were Shlomo Comandant, Bezalel Bramnik, Mordechai Yaacov Nordman, Grisha Band, Moshe Abelman and others. Chaim Davidson and Leibush Biber were the most prominent Zionist leaders in Ostroh.

The activities of the Zionist leaders were felt in all the areas of life.

Ostroh was also blessed with excellent teachers, having a strong public Zionist sense, such as Shmuel Sarir, about whom the late President of Israel Shazar used to speak a lot, Mordechai Kaplan, Yaacov Nordman, Moshe Tolpin, Tanchum Zebin, Josef Finkelstein and others.

People with a leadership ability appeared in all the Zionist youth movements in the town. Yankel Kaplan of Gordonia fell as an outstanding partisan behind Nazi lines.

There was also a Mishnah Society in the town, led by Rabbi Meir Zvi Finkel and Rabbi Pinchas Pelikop which had tens of notables who studied every single day of the year; at the “end” of their studies, they used to organize a feast at the home of the leader of the Society; I, as a child, used to enjoy those ceremonies at home and the fragrant dishes prepared by the cooks.

That was the golden age of the varied public activity in the town until the Holocaust which brought about the bitter end of the splendid community. After the city’s joining the Soviet Union in 1939, all Jewish institutions were closed. In the spring of 1940, many Jewish families were expelled from the city to remote areas of the Soviet Union.

|

|

|

| Former house of the Jewish doctor Shnayfain, 2011. Heroiv Maydanu 2 Street | One of the most beautiful mansions in the center, 2012. Nezalezhnosti 45 Street | The old house, 2015 |

In the 16-18 centuries, Ostroh became a major center of Jewish scholarship. In the city functioned one of the most famous in Poland Yeshivs, which was headed by outstanding rabbis authorities.

According to Nathan Hannover, Ostroh was a "great city of scientists and writers."

From the 2nd half of the 18th century, the city became one of the largest centers of Hasidism. The rabbi of Ostroh was a student of Israel Baal Shem Tov, Rabbi Meir Margaliot (died in 1790). He was President of Tribunal in Ostroh and the District. He was a scholar and wrote “Meir Netivim”.

Jewish Ostroh is tightly linked to the names of great Torah Scholars and Talmud Commentators as the Maharal from Prague, Rabbi Shmuel Eydels, and the great Yeshiva he has headed for tens of years, and many others.

The people told many legends and stories about Rabbi Shmuel Eydels and the great Synagogue named after him, built long before his coming to Ostroh in 1615 only thanks to the love and esteem of the community members and the fact that he lived, acted and was buried in Ostroh cemetery was the Synagogue named after him. He was considered to be the Father and Patron of the town, he was modest and hospitable. It was engraved in the stones of his house: “Strangers will not stay outside – my door will be opened to guests”. He died in 1632, leaving many books. In 1933, Ostroh Jews commemorated the 300th anniversary of his death. Rabbis and notables from all over Poland and representatives of the authorities took part in the celebrations. On that day, Jews closed their shops so as to be alone with his memory.

Ostroh also attracted people by its external look as a beautiful town immersed in greenery. The building of the Great synagogue overlooked the general view of the town and gave it a Jewish character. The Princes' palaces and the numerous towers added a special charm, as a memory of a town which, during a certain period, served as a capital for hundreds of small towns surrounding it. The fields, rivers and forest enabled excursions and outings for young people and the whole population.

According to Nathan Hannover, Ostroh was a "great city of scientists and writers."

From the 2nd half of the 18th century, the city became one of the largest centers of Hasidism. The rabbi of Ostroh was a student of Israel Baal Shem Tov, Rabbi Meir Margaliot (died in 1790). He was President of Tribunal in Ostroh and the District. He was a scholar and wrote “Meir Netivim”.

Jewish Ostroh is tightly linked to the names of great Torah Scholars and Talmud Commentators as the Maharal from Prague, Rabbi Shmuel Eydels, and the great Yeshiva he has headed for tens of years, and many others.

The people told many legends and stories about Rabbi Shmuel Eydels and the great Synagogue named after him, built long before his coming to Ostroh in 1615 only thanks to the love and esteem of the community members and the fact that he lived, acted and was buried in Ostroh cemetery was the Synagogue named after him. He was considered to be the Father and Patron of the town, he was modest and hospitable. It was engraved in the stones of his house: “Strangers will not stay outside – my door will be opened to guests”. He died in 1632, leaving many books. In 1933, Ostroh Jews commemorated the 300th anniversary of his death. Rabbis and notables from all over Poland and representatives of the authorities took part in the celebrations. On that day, Jews closed their shops so as to be alone with his memory.

Ostroh also attracted people by its external look as a beautiful town immersed in greenery. The building of the Great synagogue overlooked the general view of the town and gave it a Jewish character. The Princes' palaces and the numerous towers added a special charm, as a memory of a town which, during a certain period, served as a capital for hundreds of small towns surrounding it. The fields, rivers and forest enabled excursions and outings for young people and the whole population.

|

|

|

| Synagogue iIn Ostroh, 2012. Photo by Eugene Shnaider | ||

|

|

|

| In 2012 inside it looked like this | Synagogue in the recovery process, 2019. Photo by Ukrainer |

|

|

|

|

| Synagogue interior, 1930s | Entrance to the synagogue, view from the inside | Bimah and Aron kodesh, 1930s | Top part of Aron kodesh |

The synagogue was probably erected in the 15th century, several times rebuilt. The view of synagogue captured in the photographs acquired after the reconstruction of 1912.

The building was injured during World War II, since 1960 it was used as a warehouse, then it was abandoned and practically destroyed.

In 2016, at the initiative of the deputy of the city council, Grigory Arshinov (and partly on his personal funds), the restoration of the synagogue building began.

The building was injured during World War II, since 1960 it was used as a warehouse, then it was abandoned and practically destroyed.

In 2016, at the initiative of the deputy of the city council, Grigory Arshinov (and partly on his personal funds), the restoration of the synagogue building began.

In 1921, the number of the Jewish population of the city amounted to 7991 people (with the total number of citizens - 12 795),

in 1939 - 10,500.

The Zionist Movement in the town started operating in 1909 and went on with its activities until the Holocaust. During the reign of the Czar, there were clandestine meetings, sometimes during Christmas, when the officials were tipsy.

Cultural work was carried out in various circles: circles for Zionism, for Jewish History, Geography, etc. The young people collected donations for the Odessa Committee of Hovevei Zion. A company was also set up for organization of trips to Eretz Israel. The Bund Party was also most influential in the Jewish street.

Since 1917, public Zionist work has been carried out openly. Lectures took place on Eretz Israel and there were contacts with institutions in Eretz Israel and in Warsaw. Balls and bazaars of the Keren Kayemet (Jewish National Fund) were organized. The climax of the Zionist Movement activity in Ostrog was in the 20's and 30's when the idea of immigration to Eretz Israel struck roots. Among the first persons who immigrated in the 20's was Yaacov Fishel Feldenkreis with his wife Dvora. In spite of is being a scholar, he fitted at the age of 45 in agricultural works in Petah Tikva, in orange groves and ploughing. He was also one of the holy heroes of the riots in the country.

in 1939 - 10,500.

The Zionist Movement in the town started operating in 1909 and went on with its activities until the Holocaust. During the reign of the Czar, there were clandestine meetings, sometimes during Christmas, when the officials were tipsy.

Cultural work was carried out in various circles: circles for Zionism, for Jewish History, Geography, etc. The young people collected donations for the Odessa Committee of Hovevei Zion. A company was also set up for organization of trips to Eretz Israel. The Bund Party was also most influential in the Jewish street.

Since 1917, public Zionist work has been carried out openly. Lectures took place on Eretz Israel and there were contacts with institutions in Eretz Israel and in Warsaw. Balls and bazaars of the Keren Kayemet (Jewish National Fund) were organized. The climax of the Zionist Movement activity in Ostrog was in the 20's and 30's when the idea of immigration to Eretz Israel struck roots. Among the first persons who immigrated in the 20's was Yaacov Fishel Feldenkreis with his wife Dvora. In spite of is being a scholar, he fitted at the age of 45 in agricultural works in Petah Tikva, in orange groves and ploughing. He was also one of the holy heroes of the riots in the country.

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine