Dubno

|

|

| Holocaust memorial near the car service station (former stadium), 2014 | Holocaust Memorial (the corner of the streets of Zabrama, D. Galytskoho and Tarasa Bulby), 2016 |

The city is first mentioned in the Ipatiev Codex in 1100. In 1492, at the site of the old fortification, Prince Konstantin Ostrozhsky was building a stone castle. In 1498, Konstantin Ostrozhsky received a letter from the Lithuanian Prince Alexander to grant the status of the city, and in 1507 the Polish king Sigismund I granted him Magdeburg law.

In 1772, after the first partition of Poland, the important trade center of Lviv retired to the power of the Habsburgs. In Dubno, they began to hold a large contract fair, which continued for a month. As a result of this, an economic and cultural upsurge began in the city. For the convenience of guests and merchants, Prince Mikhail Lyubomirsky built several two-story houses around the market square, the town hall and another palace in the castle, decorated with Italian architect Domenico Merlini.

In 1772, after the first partition of Poland, the important trade center of Lviv retired to the power of the Habsburgs. In Dubno, they began to hold a large contract fair, which continued for a month. As a result of this, an economic and cultural upsurge began in the city. For the convenience of guests and merchants, Prince Mikhail Lyubomirsky built several two-story houses around the market square, the town hall and another palace in the castle, decorated with Italian architect Domenico Merlini.

In 1795, after the third section of Poland, Dubno became part of the Russian Empire. In 1797, the Duben Contracts were transferred to Novograd-Volynsky, and then to Kyiv, where they laid the foundation for the famous "Contracts" on the hem.

In 1917, after the collapse of the Russian Empire, Dubno became part of the Ukrainian People's Republic.

On March 18, 1921, after the signing of the Riga Treaty, Dubno became part of the Polish state.

On September 17, 1939, Dubno, according to the agreement of Molotov-Ribbentrop, became part of the USSR.

In 1917, after the collapse of the Russian Empire, Dubno became part of the Ukrainian People's Republic.

On March 18, 1921, after the signing of the Riga Treaty, Dubno became part of the Polish state.

On September 17, 1939, Dubno, according to the agreement of Molotov-Ribbentrop, became part of the USSR.

The first information available about Jewish merchants from Dubno dates to 1532, the oldest Jewish tombstone in the city dates to 1581. Among the leaders of the community were the well-known rabbis Yesha‘yahu ha-Levi Horowitz (known as the Shlah; 1565–1630), his first cousin Shemu’el ha-Levi Horowitz (served as rabbi from 1625–1635), and Me’ir Ashkenazi (1590–1645).

On the eve of the Khmel’nyts’kyi uprising, about 350 Jews lived in Dubno in 58 homes, which were concentrated to the south of the market square. In 1648 and 1649, Cossacks attacked the town twice. Although a number of Jews managed to escape, there were many victims, among them Yehudah ha-Hasid, head of the local rabbinical court.

According to legend, the graves of the dead were near the eastern wall of the Great Sinagogue Dubno, and there was a custom to mourn them in this place on the day of the 9 Av.

Although in 1650 only 47 Jewish homes remained, by 1662 the Jewish population had reached 625. The Princes of Lubomirsky provided the Jews with special privileges in 1699 and 1713, and by the end of the eighteenth century Dubno was home to the largest Jewish community in Volhynia.

On the eve of the Khmel’nyts’kyi uprising, about 350 Jews lived in Dubno in 58 homes, which were concentrated to the south of the market square. In 1648 and 1649, Cossacks attacked the town twice. Although a number of Jews managed to escape, there were many victims, among them Yehudah ha-Hasid, head of the local rabbinical court.

According to legend, the graves of the dead were near the eastern wall of the Great Sinagogue Dubno, and there was a custom to mourn them in this place on the day of the 9 Av.

Although in 1650 only 47 Jewish homes remained, by 1662 the Jewish population had reached 625. The Princes of Lubomirsky provided the Jews with special privileges in 1699 and 1713, and by the end of the eighteenth century Dubno was home to the largest Jewish community in Volhynia.

|

|

|

| Khazan (Kantor) Reif and choir in the synagogue Groice Shul, Dubno, 1920s | Mikvah, 2011. Phot. Vladimir Levin | Jewish houses around the synagogue, 2012. Phot. Eugene Shnaider |

In Dubli, Jews were engaged in the production of hops. The building of the hops factory, belonging to the Jews, the Fishbens brothers, has been preserved. The last owner of factory was Jew Abraham Gersh Perel.

Another rich Jewish family, engaged in the production of hops, was the Elbert family. The Elbert mansion today is one of the architectural monuments of Dubno.

Another rich Jewish family, engaged in the production of hops, was the Elbert family. The Elbert mansion today is one of the architectural monuments of Dubno.

|

|

|

| Jewish children | The owner of the tavern | Jew - bricklayer |

|

|

|

| A break in the Talmud Tora | Pupils of Talmud Tora | Children near Talmud Tora |

One of the architectural monuments of Dubno is a former Contract House, which is also related to Jewish history.

Contract house on the Market square was built in the XIX century. to serve the famous Dubno Contracts. After the transfer of fairs to Zvyagel (Novograd-Volynsky), and then in Kyiv the house lost its function. At the beginning of the XX century it was acquired by a Jewish water carrier named Greenberg, who returned the day before from the army, where he took part in the Russian-Japanese war.

According to legend, Greenberg found a treasure in Manchuria, which he took with him the whole war in the drum. Returning to Dubno, he headed the watercarriers guild and acquired several houses, including the former House of contracts. The former water carrier spoke about the source of wealth only before his death in 1939.

According to the old-timers, every year on his birthday, Greenberg put several barrels of beer and a good snack for Dubno water carriers...

Contract house on the Market square was built in the XIX century. to serve the famous Dubno Contracts. After the transfer of fairs to Zvyagel (Novograd-Volynsky), and then in Kyiv the house lost its function. At the beginning of the XX century it was acquired by a Jewish water carrier named Greenberg, who returned the day before from the army, where he took part in the Russian-Japanese war.

According to legend, Greenberg found a treasure in Manchuria, which he took with him the whole war in the drum. Returning to Dubno, he headed the watercarriers guild and acquired several houses, including the former House of contracts. The former water carrier spoke about the source of wealth only before his death in 1939.

According to the old-timers, every year on his birthday, Greenberg put several barrels of beer and a good snack for Dubno water carriers...

They were born in Dubno:

- Yaakov Ben Wolf Krantz is one of the most popular preachers for Yiddish. Kranz maintained a connection with a number of outstanding rabbis of his time, including with the Vilnius Gaon. In his sermons, Krantz widely used ethical, homiletic, galachic and Kabbalistic works, setting them out in a simple and affordable form.

- Solomon Ben Joel Dubno is the interpreter of the Torah. He lived in the II half of the 18th century. He was the co-author of Moses Mendelssohn in the publication of the Torah in German.

In 1912, an ethnographic expedition under the leadership of Semen An-sky (Shlome-Zanvl Rappoport) visited Dubno. The photographer of the expedition Solomon Yudovin took several wonderful photos.

Rivne region

Sources:

- Benyamin Lukin, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Dubno. Translated by Michael Aronson;

- Sefer zikaron Dubno. Editor: Y.Adini, Tel Aviv, Dubno Organization in Israel, 1966. Translated by Yocheved Klausner, JewishGen, Inc;

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron;

- Yad Vashem. Dubno

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider;

- Juliusz Kłos (1916), Shimon Zaychik (1930s), Henryk Poddebski (1922), I.Tabarowski (1914). Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk;

- Eugene M. Avrutin, Valerii Dymshits, Alexander Lvov, Harriet Murav and Alla Sokolova. Photographing the Jewish Nation. Pictures from S.An-sky's Ethnographic Expeditions;

- Sefer zikaron Dubno;

- Serhiy LS, ЯдвигаВереск: Wikipedia. Dubno territorial community

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Dubno

- Romek Pawluk

- Sergey Kravtsov, Vladimir Levin: The Center for Jewish Art. Dubno

- Ukrainian architectural monuments. Dubno

- World Association Of Wolynian Jews in Israel. Kehilat Dubno

- Benyamin Lukin, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Dubno. Translated by Michael Aronson;

- Sefer zikaron Dubno. Editor: Y.Adini, Tel Aviv, Dubno Organization in Israel, 1966. Translated by Yocheved Klausner, JewishGen, Inc;

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron;

- Yad Vashem. Dubno

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider;

- Juliusz Kłos (1916), Shimon Zaychik (1930s), Henryk Poddebski (1922), I.Tabarowski (1914). Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk;

- Eugene M. Avrutin, Valerii Dymshits, Alexander Lvov, Harriet Murav and Alla Sokolova. Photographing the Jewish Nation. Pictures from S.An-sky's Ethnographic Expeditions;

- Sefer zikaron Dubno;

- Serhiy LS, ЯдвигаВереск: Wikipedia. Dubno territorial community

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Dubno

- Romek Pawluk

- Sergey Kravtsov, Vladimir Levin: The Center for Jewish Art. Dubno

- Ukrainian architectural monuments. Dubno

- World Association Of Wolynian Jews in Israel. Kehilat Dubno

|

|

|

| Synagogue in Dubno, 2012. Phot. Eugene Shnaider | Synagogue in Dubno, 2015. Phot. Eugene Shnaider | Synagogue in Dubno, 2015 |

At the beginning of the twentieth century, two modernized heders (Heder metukan), a Talmud Torah, a state Jewish school, and two private Jewish schools (one for men and one for women) were functioning.

Practically all the local industrial and commercial enterprises belonged to Jews.

The town suffered extensive damage during World War I, and anti-Jewish pogroms took place between 1917 and 1919. During the Civil War, Dubno often passed from hand to hand, which seriously affected the Jewish population of the city. Jewish pogroms repeatedly broke out, of which the most bloody were the pogrom arranged by units of the Russian army in December 1917, and the pogrom in the summer of 1919, when rebel gangs entered the city. During this pogrom, about 300 people were killed and wounded.

Practically all the local industrial and commercial enterprises belonged to Jews.

The town suffered extensive damage during World War I, and anti-Jewish pogroms took place between 1917 and 1919. During the Civil War, Dubno often passed from hand to hand, which seriously affected the Jewish population of the city. Jewish pogroms repeatedly broke out, of which the most bloody were the pogrom arranged by units of the Russian army in December 1917, and the pogrom in the summer of 1919, when rebel gangs entered the city. During this pogrom, about 300 people were killed and wounded.

In 1716, the Dubno Jewish community was persecuted, accused of concealing two women who had converted to Judaism. Nevertheless, the Jewish population expanded with the town’s growing importance as a center of trade.

In 1765, 1923 Jews lived in Dubno, they owned 170 houses.

In 1787, there were 2,325 Jews in Dubno.

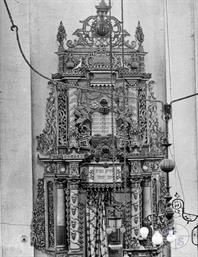

The Great Synagogue was completed in 1794, and from that year until 1819, three Jewish printing house operated in the town. In 1802, another printing house was opened.

From the 1820s Dubno was an important center of the Haskalah; among its leading figures were Ze’ev Volf Adelson and Avraham Ber Gottlober in the 1830s. The main opponents of the maskilim were the Misnagdim (opponents of the Hasidim), among whom Rabbi Hayim Mordekhai Margaliot (1815–1829) enjoyed special authority. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, several Hasidic prayer halls were established, the largest being that of Barukh ha-Levi Yuzefov.

In 1857, there were 15 synagogues and prayer houses in Dubno, and 22 heders.

In 1897 there were 7,108 Jews living in Dubno (about half the town’s population).

In 1765, 1923 Jews lived in Dubno, they owned 170 houses.

In 1787, there were 2,325 Jews in Dubno.

The Great Synagogue was completed in 1794, and from that year until 1819, three Jewish printing house operated in the town. In 1802, another printing house was opened.

From the 1820s Dubno was an important center of the Haskalah; among its leading figures were Ze’ev Volf Adelson and Avraham Ber Gottlober in the 1830s. The main opponents of the maskilim were the Misnagdim (opponents of the Hasidim), among whom Rabbi Hayim Mordekhai Margaliot (1815–1829) enjoyed special authority. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, several Hasidic prayer halls were established, the largest being that of Barukh ha-Levi Yuzefov.

In 1857, there were 15 synagogues and prayer houses in Dubno, and 22 heders.

In 1897 there were 7,108 Jews living in Dubno (about half the town’s population).

In the 1920s thanks to significant help from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Jewish economic life was revived. As before, most of the Jews were occupied in handicrafts, in the sale of agricultural products, and in small local enterprises.

Jews amounted to about 60 percent of the city population (5,315 in 1921 and 7,364 in 1931), but they generally did not have a majority vote in municipal government.

A Tarbut school, a gymnasium, schools with teaching in Hebrew and Yidish, a Talmud Torah, a Jewish cooperative bank, an orphanage, a kindergarten, a nursing house and a hospital all served the community.

All Zionist parties and youth movements were represented by energetic local organizations. However, with the annexation of western Volhynia to the USSR in September 1939, all Jewish public and political institutions were closed.

On the eve of the Nazi invasion, about 12,000 Jews lived in Dubno, including more than 4,000 refugees from Poland.

Jews amounted to about 60 percent of the city population (5,315 in 1921 and 7,364 in 1931), but they generally did not have a majority vote in municipal government.

A Tarbut school, a gymnasium, schools with teaching in Hebrew and Yidish, a Talmud Torah, a Jewish cooperative bank, an orphanage, a kindergarten, a nursing house and a hospital all served the community.

All Zionist parties and youth movements were represented by energetic local organizations. However, with the annexation of western Volhynia to the USSR in September 1939, all Jewish public and political institutions were closed.

On the eve of the Nazi invasion, about 12,000 Jews lived in Dubno, including more than 4,000 refugees from Poland.

Germans captured Dubno on June 25, 1941. The Jews were required to wear a Star of David armband (replaced with a yellow badge in October). Apparently at about the same time, several dozen Jews associated with the NKVD were shot to death on the Panienski Bridge in the town.

In murder operations on July 22 and August 22, 1941 German units, assisted by Ukrainian auxiliary police, killed over 1,000 Jewish men (and several women) at the Jewish cemetery. In early August a twelve-member Judenrat (Jewish council) was appointed, headed by Dr. Konrad Taubenfeld. The Judenrat was ordered to collect money and household goods as "contributions" for the Germans. In mid-August the Jews also had to hand over all their gold, silver, and other valuables. In December 1941 the Judenrat had to collect and deliver to the Germans all fur and woolen items.

A ghetto was officially established on April 2, 1942, the first day of Passover, in the old Jewish section of the town. On the same day a very high wooden fence topped with barbed wire was constructed between the buildings forming the outer border of the ghetto. Jews were sent to perform forced labor – on construction sites and rail-roads, and in factories and in workshops specializing in products needed by the Germans.

In mid-May 1942 the ghetto was divided into two sections. One part was for the skilled workers and craftsmen and their families, and the other for people without such skills. Skilled workers were given special certificates.

On May 26-27, 1942 the part of the ghetto inhabited by those without skills useful to the Germans was liquidated, with women, children, and elderly people being shot to death at the Surmicze airfield outside of town, while the men were shot to death at Szibiena Hura also outside of town. Approximately 4,000 Jews were murdered during these two days. Over the next four months, killings and the harassment of individuals increased. Many Jews prepared hiding places.

In August 1942 Jews from nearby villages were taken to the skilled worker's ghetto, the population of which rose to 4,500. There was hunger, starvation, and epidemics there. This ghetto was liquidated on October 5, 1942, when most of its inmates were shot to death at the Surmicze airfield.

After this murder operation the remaining 240 skilled workers were given "secure" certificates" and remained in the ghetto. Following the October 5 murder operation, in order to lure survivors into the open, the Germans posted notices all over the ghetto promising that no harm would come to those who would come out of hiding willingly, since they were needed for work. During the following two weeks about 150 Jews came out of hiding.

On October 24, 1942 in a final murder operation, the several hundred remaining Jews in the ghetto (except for 10 specialists) were killed at Szibiena Hura. According to one testimony, approximately 100 Jews who had been caught in hiding by the Germans after the final liquidation of the ghetto were shot to death on Bozhenko Street. Thus, by the end of October 1942, Dubno was officially declared "cleansed of Jews" (Judenrein).

After the liberation of the city, a small number of Jews returned from shelters and evacuation.

According to the all-Ukrainian census of the population of 2001, the Jews did not live in Dubno.

In murder operations on July 22 and August 22, 1941 German units, assisted by Ukrainian auxiliary police, killed over 1,000 Jewish men (and several women) at the Jewish cemetery. In early August a twelve-member Judenrat (Jewish council) was appointed, headed by Dr. Konrad Taubenfeld. The Judenrat was ordered to collect money and household goods as "contributions" for the Germans. In mid-August the Jews also had to hand over all their gold, silver, and other valuables. In December 1941 the Judenrat had to collect and deliver to the Germans all fur and woolen items.

A ghetto was officially established on April 2, 1942, the first day of Passover, in the old Jewish section of the town. On the same day a very high wooden fence topped with barbed wire was constructed between the buildings forming the outer border of the ghetto. Jews were sent to perform forced labor – on construction sites and rail-roads, and in factories and in workshops specializing in products needed by the Germans.

In mid-May 1942 the ghetto was divided into two sections. One part was for the skilled workers and craftsmen and their families, and the other for people without such skills. Skilled workers were given special certificates.

On May 26-27, 1942 the part of the ghetto inhabited by those without skills useful to the Germans was liquidated, with women, children, and elderly people being shot to death at the Surmicze airfield outside of town, while the men were shot to death at Szibiena Hura also outside of town. Approximately 4,000 Jews were murdered during these two days. Over the next four months, killings and the harassment of individuals increased. Many Jews prepared hiding places.

In August 1942 Jews from nearby villages were taken to the skilled worker's ghetto, the population of which rose to 4,500. There was hunger, starvation, and epidemics there. This ghetto was liquidated on October 5, 1942, when most of its inmates were shot to death at the Surmicze airfield.

After this murder operation the remaining 240 skilled workers were given "secure" certificates" and remained in the ghetto. Following the October 5 murder operation, in order to lure survivors into the open, the Germans posted notices all over the ghetto promising that no harm would come to those who would come out of hiding willingly, since they were needed for work. During the following two weeks about 150 Jews came out of hiding.

On October 24, 1942 in a final murder operation, the several hundred remaining Jews in the ghetto (except for 10 specialists) were killed at Szibiena Hura. According to one testimony, approximately 100 Jews who had been caught in hiding by the Germans after the final liquidation of the ghetto were shot to death on Bozhenko Street. Thus, by the end of October 1942, Dubno was officially declared "cleansed of Jews" (Judenrein).

After the liberation of the city, a small number of Jews returned from shelters and evacuation.

According to the all-Ukrainian census of the population of 2001, the Jews did not live in Dubno.

Rivne region - list of settlements and location of objects

Dubno, 2012, 2015, 2024

Dubno, 2012, 2015, 2024

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine