Zbarazh

Ternopil region

Sources:

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. Translated by JewishGen, Inc.

- Федорів Тетяна. Нариси до історії євреїв Збаража. "Новий" єврейський цвинтар міста. Тернопіль: "Лібра Терра", 2019. - 116 с.: іл.

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia

Photo:

- Tetiana Fedoriv

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona, Zbaraż

- FB Group Збараж вчора і сьогодні, published by Vitaliy Gontaruk

- JewishGen, Zbaraż Jewish Cemetery, published by August Thiry

- JewishGen, Zbaraż Businesses and Shopkeepers, published by August Thiry

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. Translated by JewishGen, Inc.

- Федорів Тетяна. Нариси до історії євреїв Збаража. "Новий" єврейський цвинтар міста. Тернопіль: "Лібра Терра", 2019. - 116 с.: іл.

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia

Photo:

- Tetiana Fedoriv

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona, Zbaraż

- FB Group Збараж вчора і сьогодні, published by Vitaliy Gontaruk

- JewishGen, Zbaraż Jewish Cemetery, published by August Thiry

- JewishGen, Zbaraż Businesses and Shopkeepers, published by August Thiry

|

|

|

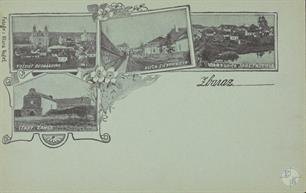

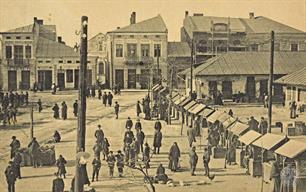

| Polish postcard with views of Zbarazh, beginning 20th century | Fragment of panorama of Zbarazh, beg. 20th The synagogue is visible in background | Market in Zbarazh, beginning 20th century |

Zbarazh, city (since 1939), district center in the Ternopol region (until 2019). (Ukraine). In the 16-18 centuries - part of the Commonwealth. In 19 - beginning 20th century - in province of Galicia in Austria-Hungary. In 1919–39 - as part of Poland, in 1939–91 - USSR.

In 1765 in Zbarazh lived 910 Jews,

in 1880 - 3768 (46.7%),

in 1890 - 3631 (41.3%),

in 1900 - 2896 (34.8%),

in 1910 - 329 (32.9%),

in 1921 - 2982 (35.5%),

in 1931 - 2870 Jews.

Jews lived in Zbarazh since end of15th century. In the 1st half 17th century the synagogue was built.

In the 2nd half 17th century Rabbi of Zbarazh was Moishe Segal, in the beginning 18th century - Schlome Charif, in the middle 18th century - Alter Teumim, then Moishe Rokeah, in the end 18th century - Meshulem-Fayvish Geler.

In 1858–93, the Rabbi court of Zbarazh headed Ieshiyahu Babad.

In the beginning 20th century in Zbarazh was the Hasidic courtyard of Yom-Tov Lipman Geler.

Since the end 19th century various of Zionist organisations operated in Zbarazh.

During the First World War, a Hebrew school was founded in the city, which most of the Jewish children attended. There were also many cheders in which small children learned. However, most of the children learned in Hebrew schools. Besides the schools, there were cultural institutions such as public libraries and a dramatic troupe under the management of Dr. Nissan Speizer. All of this was managed by the Yehudah Halevi Association. There were also kindergartens.

Since 1907 a school Chinuch worked with teaching in Hebrew. This school was highly influential. Most of the Jews in the city, from the assimilated to the ultra–Orthodox, sent their children there.

In addition, evening courses for adults were offered, and there was also a public library. The municipal association, which supported the Hebrew language, was also active in this framework.

In the years 1923–1924, courses were offered under the aegis of the Jewish Union for People's Schools and High Schools in Levov.

There also existed another two complementary schools, whose financial situation was extremely poor.

In 1922, the sports association, Hagibor, was established. It was particularly strong in soccer.

In 1765 in Zbarazh lived 910 Jews,

in 1880 - 3768 (46.7%),

in 1890 - 3631 (41.3%),

in 1900 - 2896 (34.8%),

in 1910 - 329 (32.9%),

in 1921 - 2982 (35.5%),

in 1931 - 2870 Jews.

Jews lived in Zbarazh since end of15th century. In the 1st half 17th century the synagogue was built.

In the 2nd half 17th century Rabbi of Zbarazh was Moishe Segal, in the beginning 18th century - Schlome Charif, in the middle 18th century - Alter Teumim, then Moishe Rokeah, in the end 18th century - Meshulem-Fayvish Geler.

In 1858–93, the Rabbi court of Zbarazh headed Ieshiyahu Babad.

In the beginning 20th century in Zbarazh was the Hasidic courtyard of Yom-Tov Lipman Geler.

Since the end 19th century various of Zionist organisations operated in Zbarazh.

During the First World War, a Hebrew school was founded in the city, which most of the Jewish children attended. There were also many cheders in which small children learned. However, most of the children learned in Hebrew schools. Besides the schools, there were cultural institutions such as public libraries and a dramatic troupe under the management of Dr. Nissan Speizer. All of this was managed by the Yehudah Halevi Association. There were also kindergartens.

Since 1907 a school Chinuch worked with teaching in Hebrew. This school was highly influential. Most of the Jews in the city, from the assimilated to the ultra–Orthodox, sent their children there.

In addition, evening courses for adults were offered, and there was also a public library. The municipal association, which supported the Hebrew language, was also active in this framework.

In the years 1923–1924, courses were offered under the aegis of the Jewish Union for People's Schools and High Schools in Levov.

There also existed another two complementary schools, whose financial situation was extremely poor.

In 1922, the sports association, Hagibor, was established. It was particularly strong in soccer.

After the beginning 2nd World War in Zbarazh arrived thousands of refugees from Western Poland Districts. At that time, there were more than 5,000 Jews in the city.

In autumn, 1939, the activities of the Jewish institutions, political parties and public organizations ceased. That was under the administration of the Soviets, who took control of the city as a result of an agreement between them and the Germans. Governmental institutions (and Polish governance in general) were dismantled and no longer existed. Only the synagogues were not damaged, and the faithful continued to pray there.

Wholesale commerce was liquidated and, after the entire economy of the city was nationalized, retailers gradually closed their stores. Many craftsmen were forced into cooperatives. At the end of June, 1940, many refugees in the city were taken to the Soviet Union.

In autumn, 1939, the activities of the Jewish institutions, political parties and public organizations ceased. That was under the administration of the Soviets, who took control of the city as a result of an agreement between them and the Germans. Governmental institutions (and Polish governance in general) were dismantled and no longer existed. Only the synagogues were not damaged, and the faithful continued to pray there.

Wholesale commerce was liquidated and, after the entire economy of the city was nationalized, retailers gradually closed their stores. Many craftsmen were forced into cooperatives. At the end of June, 1940, many refugees in the city were taken to the Soviet Union.

With the Russian conquest in 1914, followed by an interval when Poland and the Ukraine temporarily held power, and then in 1920 under Bolshevik rule, chaos reigned in the city, and Jewish stores were destroyed. However, besides that, the Jews did not suffer particularly from robbery and other acts of violence.

With the installation of the Polish government, those who had collaborated with the Soviets and the Ukrainians fled, and the Polish authorities imprisoned 25 men: Poles, Ukrainians and a number of Jews. Most of these were freed within short order, but three were sentenced to death and were shot in the fields outside the town.

With the abatement of fighting in 1920, the refugees who had fled during the hostilities began to return to the city. In order to help them, an assistance committee was established, one that was particularly active in 1924. Earlier, the six factories in the city had ceased operating. After they were reorganized in 1921, four of these factories were in operation, and the number of those employed was 43. Jewish employees at that time comprised 36.6 per cent of all employees in the city.

From 1928 and onward, a charity fund operated in Zbarazh. In 1929, this fund distributed loans in the sum of 1,1010 [sic] zloty. From 1930, the Union of Cooperatives for Jews in Poland approved credit in the amount of 10,000 zloty for the city's commercial bank.

In 1930, an additional Jewish bank was established in the city, Bank Credit Partners, a successful venture that helped many merchants and artisans.

The charity fund's agricultural activities during period from 1933 to 1937 testify to the financial state of the Jews of Zbarazh.

With the installation of the Polish government, those who had collaborated with the Soviets and the Ukrainians fled, and the Polish authorities imprisoned 25 men: Poles, Ukrainians and a number of Jews. Most of these were freed within short order, but three were sentenced to death and were shot in the fields outside the town.

With the abatement of fighting in 1920, the refugees who had fled during the hostilities began to return to the city. In order to help them, an assistance committee was established, one that was particularly active in 1924. Earlier, the six factories in the city had ceased operating. After they were reorganized in 1921, four of these factories were in operation, and the number of those employed was 43. Jewish employees at that time comprised 36.6 per cent of all employees in the city.

From 1928 and onward, a charity fund operated in Zbarazh. In 1929, this fund distributed loans in the sum of 1,1010 [sic] zloty. From 1930, the Union of Cooperatives for Jews in Poland approved credit in the amount of 10,000 zloty for the city's commercial bank.

In 1930, an additional Jewish bank was established in the city, Bank Credit Partners, a successful venture that helped many merchants and artisans.

The charity fund's agricultural activities during period from 1933 to 1937 testify to the financial state of the Jews of Zbarazh.

In the municipal and communal arena, whenever city elections drew closer, the Jews of Zbarazh would experience ups and downs.

In 1927, a Jewish bloc called Ichud was established, which included all of the Zionist parties–merchants, artisans, the Mizrachi and even the ultra–Orthodox. Because of the pressure of the local authorities, which issued slanderous fabrications and threats, that year the three national parties lost power and the conservative powers–the National Democrats and the Ukrainian anti–Semites–gained in strength.

In 1931, the situation changed for the better, and a Jew was elected mayor of the city.

But in 1933, the situation again worsened. In the elections to the municipal council, there wasn't even one Jew among the 16 elected. In the elections of 1939, four Jews were elected to the municipal council, in addition to seven Poles and one Ukrainian; however, no Jew was elected to the municipality administration.

Nevertheless, a number of Jews worked in key posts in the municipality.

In the elections to the community council in 1934, as a result of an agreement among all of the parties, the results were as follows: General Zionists–two mandates, Hitachdut–two mandates, Mizrachi–one mandate, Revisionists–two mandates, and Yad Charutzim–one mandate. In the first meeting, Dr. Zindel Segal–a very popular man, a physician–was elected chairman. But the community council did not last long, apparently because of internal difficulties. In June, 1934, it was dissolved by the authorities and a commissary was appointed.

In 1927, a Jewish bloc called Ichud was established, which included all of the Zionist parties–merchants, artisans, the Mizrachi and even the ultra–Orthodox. Because of the pressure of the local authorities, which issued slanderous fabrications and threats, that year the three national parties lost power and the conservative powers–the National Democrats and the Ukrainian anti–Semites–gained in strength.

In 1931, the situation changed for the better, and a Jew was elected mayor of the city.

But in 1933, the situation again worsened. In the elections to the municipal council, there wasn't even one Jew among the 16 elected. In the elections of 1939, four Jews were elected to the municipal council, in addition to seven Poles and one Ukrainian; however, no Jew was elected to the municipality administration.

Nevertheless, a number of Jews worked in key posts in the municipality.

In the elections to the community council in 1934, as a result of an agreement among all of the parties, the results were as follows: General Zionists–two mandates, Hitachdut–two mandates, Mizrachi–one mandate, Revisionists–two mandates, and Yad Charutzim–one mandate. In the first meeting, Dr. Zindel Segal–a very popular man, a physician–was elected chairman. But the community council did not last long, apparently because of internal difficulties. In June, 1934, it was dissolved by the authorities and a commissary was appointed.

After the German invasion on June 22, 1941, a large group of Jews from the city fled eastward. The Germans entered the city on July 6, 1941. Two days earlier, after the Soviets had left the city, riots had taken place during which a number of Jews had been murdered by the local Ukrainians. The pretext for the riots was the discovery of the bodies of political prisoners who had been killed by the Soviets before their retreat.

Immediately after the Germans entered the city, they murdered a number of Jews in the streets, among them some of the leading citizens of the city: Meir Hindes and his wife, Aharon Klar, Joseph Segal, Israel Sommerstein, and others. The Jews of the city could not even give them the final honor of burial in the cemetery due to the fear of German reprisals, and so they buried them in the large synagogue's courtyard. In the middle of July, 1941, the Germans demanded the establishment of a Judenrat. They turned to past community leaders. However, Zusia Hammer, who had been chairman of the community's committee before the war, refused to accept a position in the Judenrat, citing his poor state of health.

Within a short period of time, Greenfeld, a refugee from western Poland, became head of the Judenrat. From the very beginning, he obeyed the Germans' orders, ignored the interests of the community and acted to its detriment.

On September 6, 1941, Jewish men were summoned to present themselves in the square facing the municipal building. Those who gathered there were surrounded by Ukrainian police and SS units that had come from Tarnopol. A selection was made of 74 men–principally maskilim and almost all of the intelligentsia. They were taken to the Lubianki forest, where they were killed and thrown into pits that they themselves had been forced to dig.

In the winter of 1941–1942 and in the spring of 1942, Jewish men were taken from Zbarazh to work camps in the vicinity: Zborov, Kaminka–Stromilova, Borki–Vilki, Halubotzki–Vilki [Lubotzky–Vilki?], Podvolotziskeh [Pidvolochysk?], Maksimovkah, Roznoshenske and Lubianki.

In June, 1942, 600 old and sick people were taken from the city in the direction of Tarnopol and killed. In August 31 and on September 1, 1942, a mass “action” took place, in which a few hundred Jews were sent to be liquidated in the Belzetz camp.

In autumn, 1942, a ghetto was set up in Zbarazh, to which Jews were brought from the nearby communities of Skalat, Hrymayliv (Grzymalow), Podvolotziskeh [Pidvolochysk?] and Nobi–s'olo.

Although the ghetto was not sealed off, the ability to leave it was restricted, and obtaining food was difficult.

The Jews of the city began to prepare hiding places in the ghetto in anticipation of future “actions.” They also looked for places to hide in the nearby forests, in “bunkers” and with Christian acquaintances.

By the beginning of October, 1942, few Jews made an appearance in the city.

On October 20–22, 1942, there was another “action,” in the course of which more than 1,000 people were rounded up. Many of them were sent to be liquidated in Belzetz, and a group of men was transferred to the Yanovsky camp in Levov.

The process of the destruction of the Jewish community continued on November 8 and 9, 1942. Again, about 1,000 thousand men were taken to Belzetz. Some young people jumped from the moving train, of whom a few succeeded in returning to the ghetto in Zbarazh.

The winter of 1942–1943 saw a worsening of the situation for the survivors in the city. Hunger and illness caused many deaths.

On the other hand, information about German losses on the front encouraged the Jews of the city to bolster their efforts to save themselves. Bunkers were built in the nearby forests, but getting food for an extended period was difficult. Also, the hostile attitudes of the local population made such shelters dangerous. These residents constantly hunted down people hiding in the forests and in pits. Thus, the possibility of being saved in that way was difficult and circumscribed.

Immediately after the Germans entered the city, they murdered a number of Jews in the streets, among them some of the leading citizens of the city: Meir Hindes and his wife, Aharon Klar, Joseph Segal, Israel Sommerstein, and others. The Jews of the city could not even give them the final honor of burial in the cemetery due to the fear of German reprisals, and so they buried them in the large synagogue's courtyard. In the middle of July, 1941, the Germans demanded the establishment of a Judenrat. They turned to past community leaders. However, Zusia Hammer, who had been chairman of the community's committee before the war, refused to accept a position in the Judenrat, citing his poor state of health.

Within a short period of time, Greenfeld, a refugee from western Poland, became head of the Judenrat. From the very beginning, he obeyed the Germans' orders, ignored the interests of the community and acted to its detriment.

On September 6, 1941, Jewish men were summoned to present themselves in the square facing the municipal building. Those who gathered there were surrounded by Ukrainian police and SS units that had come from Tarnopol. A selection was made of 74 men–principally maskilim and almost all of the intelligentsia. They were taken to the Lubianki forest, where they were killed and thrown into pits that they themselves had been forced to dig.

In the winter of 1941–1942 and in the spring of 1942, Jewish men were taken from Zbarazh to work camps in the vicinity: Zborov, Kaminka–Stromilova, Borki–Vilki, Halubotzki–Vilki [Lubotzky–Vilki?], Podvolotziskeh [Pidvolochysk?], Maksimovkah, Roznoshenske and Lubianki.

In June, 1942, 600 old and sick people were taken from the city in the direction of Tarnopol and killed. In August 31 and on September 1, 1942, a mass “action” took place, in which a few hundred Jews were sent to be liquidated in the Belzetz camp.

In autumn, 1942, a ghetto was set up in Zbarazh, to which Jews were brought from the nearby communities of Skalat, Hrymayliv (Grzymalow), Podvolotziskeh [Pidvolochysk?] and Nobi–s'olo.

Although the ghetto was not sealed off, the ability to leave it was restricted, and obtaining food was difficult.

The Jews of the city began to prepare hiding places in the ghetto in anticipation of future “actions.” They also looked for places to hide in the nearby forests, in “bunkers” and with Christian acquaintances.

By the beginning of October, 1942, few Jews made an appearance in the city.

On October 20–22, 1942, there was another “action,” in the course of which more than 1,000 people were rounded up. Many of them were sent to be liquidated in Belzetz, and a group of men was transferred to the Yanovsky camp in Levov.

The process of the destruction of the Jewish community continued on November 8 and 9, 1942. Again, about 1,000 thousand men were taken to Belzetz. Some young people jumped from the moving train, of whom a few succeeded in returning to the ghetto in Zbarazh.

The winter of 1942–1943 saw a worsening of the situation for the survivors in the city. Hunger and illness caused many deaths.

On the other hand, information about German losses on the front encouraged the Jews of the city to bolster their efforts to save themselves. Bunkers were built in the nearby forests, but getting food for an extended period was difficult. Also, the hostile attitudes of the local population made such shelters dangerous. These residents constantly hunted down people hiding in the forests and in pits. Thus, the possibility of being saved in that way was difficult and circumscribed.

On April 7, 1943, more than 1,000 Jews of the city and the surrounding vicinity who were in the ghetto were taken to be killed at a site close to the city.

On June 8, 1943, the ghetto was entirely destroyed. The last of the Jews of the city were killed in mass graves next to the city. Zbarazh was proclaimed judenrein. Only small groups of Jews still survived in the surrounding forests, and a handful of Jews hid with gentiles.

Among the gentiles who hid a few of the Jews of Zbarazh, the following should be noted: Joseph Ibshkivitz (in the past, school administrator, died in Auschwitz) and the previous head of the city, Szober. They helped their Jewish acquaintances find refuge in the village of Kartovatzah, and tended to their needs.

But the vast majority of the local residents denounced the hiding Jews and turned them over to the Germans–a phenomenon that continued until the last days of Nazi rule.

In February, 1944, retreating Wehrmacht soldiers came upon Jews of the city hiding in the surrounding villages and murdered them.

On March 6, 1944, the Soviets liberated the city. Among the Jews of the city, only a few individuals were saved. Those who survived left the city for Warsaw, from which they went to the land of Israel and to other countries, such as the United States, Australia, Argentina and Canada.

On June 8, 1943, the ghetto was entirely destroyed. The last of the Jews of the city were killed in mass graves next to the city. Zbarazh was proclaimed judenrein. Only small groups of Jews still survived in the surrounding forests, and a handful of Jews hid with gentiles.

Among the gentiles who hid a few of the Jews of Zbarazh, the following should be noted: Joseph Ibshkivitz (in the past, school administrator, died in Auschwitz) and the previous head of the city, Szober. They helped their Jewish acquaintances find refuge in the village of Kartovatzah, and tended to their needs.

But the vast majority of the local residents denounced the hiding Jews and turned them over to the Germans–a phenomenon that continued until the last days of Nazi rule.

In February, 1944, retreating Wehrmacht soldiers came upon Jews of the city hiding in the surrounding villages and murdered them.

On March 6, 1944, the Soviets liberated the city. Among the Jews of the city, only a few individuals were saved. Those who survived left the city for Warsaw, from which they went to the land of Israel and to other countries, such as the United States, Australia, Argentina and Canada.

|

|

|

| Synagogue in Zbarazh, 2015 | Synagogue after the World War 2 | Bas-reliefs in the interior of synagogue |

|

|

|

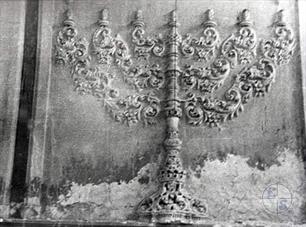

| Griffins | Menorah |

|

|

|

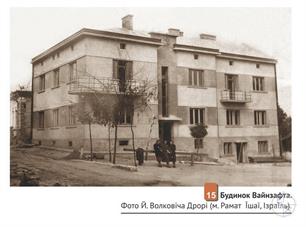

| Former house of Weinzaft. Shevchenka street | Former laundry of Raizenbaum. Hrushevskoho street, 17 | Former bakery of Sender, 2017. Franko square |

|

|

|

| Old Jewish cemetery. Photos taken by Belgian soldiers in 1916 | Old cemetery was destroyed after World War 2 by Soviet authorities | Tombstone from Old cemetery in New Jewish cemetery |

Despite these problems, lively national and public activity took place in Zbarazh.

In 1917, a Hashomer Hatzair branch was founded in Zbarazh, with a membership of hundreds of youths from all strata of the city.

In 1920–21, the first group made aliyah. Hashomer Hatzair experienced a brief hiatus, following which it returned to intensified activity. It organized all of the poor of the city. In 1928, a robust division of Gordoniyah (a popular youth pioneer federation) was active, and continued its activities until 1939.

In 1919, a Union of Zionist Women was operating, and in that year a Yardanyah Union of Jewish students was founded. In 1930, a branch of Hashomer Hadati began activities in the city, as did as a number of other organizations, such as the Hebrew Youth (whose name was later changed to Zionist Youth), Akiva and Beitar. In 1934, a vigorous branch of Poalei Tzion was founded, with 70 members.

In 1935, a branch of Achavah was established, with 40 members. In 1939, a branch of Hashachar, a radical Zionist youth movement, functioned in Zbarazh. In the elections for the Zionist Congress in 1935, the General Zionists received 234 votes, Mizrachi 279 votes, and Hitachdut Poalei Tzion 516 votes.

In 1917, a Hashomer Hatzair branch was founded in Zbarazh, with a membership of hundreds of youths from all strata of the city.

In 1920–21, the first group made aliyah. Hashomer Hatzair experienced a brief hiatus, following which it returned to intensified activity. It organized all of the poor of the city. In 1928, a robust division of Gordoniyah (a popular youth pioneer federation) was active, and continued its activities until 1939.

In 1919, a Union of Zionist Women was operating, and in that year a Yardanyah Union of Jewish students was founded. In 1930, a branch of Hashomer Hadati began activities in the city, as did as a number of other organizations, such as the Hebrew Youth (whose name was later changed to Zionist Youth), Akiva and Beitar. In 1934, a vigorous branch of Poalei Tzion was founded, with 70 members.

In 1935, a branch of Achavah was established, with 40 members. In 1939, a branch of Hashachar, a radical Zionist youth movement, functioned in Zbarazh. In the elections for the Zionist Congress in 1935, the General Zionists received 234 votes, Mizrachi 279 votes, and Hitachdut Poalei Tzion 516 votes.

In 1933–1934, the entire amount of loans was 6,235 zloty. In 1935–36, 89 loans were extended for a sum total of 7,380 zloty, and in 1936–1937, loans were given to 93 professionals, 126 small merchants, 6 farmers and 45 others.

In 1934, the situation deteriorated, when the city and government imposed heavy taxes on residents, including the Jews. This placed an additional burden upon the Jews' ability to provide assistance for the needy.

In 1935, a children's shelter functioned alongside the local WIZO. The Merchants' Union committee established a special fund to assist its members. In 1939, the Cooperative Bank entered into financial difficulties, which affected its functions and had an impact on those who required its services.

In 1934, the situation deteriorated, when the city and government imposed heavy taxes on residents, including the Jews. This placed an additional burden upon the Jews' ability to provide assistance for the needy.

In 1935, a children's shelter functioned alongside the local WIZO. The Merchants' Union committee established a special fund to assist its members. In 1939, the Cooperative Bank entered into financial difficulties, which affected its functions and had an impact on those who required its services.

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate