Stryy

Lviv region

Sources:

- Jewish encyclopedia World ORT

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Virtual Shtetl. Stryi

Photo:

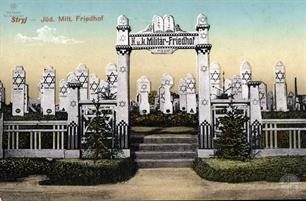

- Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Stryy New Jewish Cemetery, Stryy Old Jewish Cemetery

- Vladimir Levin, Boris Khaimovich, Eva Maria Kraiss: Center for Jewish art. Stryi (Стрий)

- Сергій Хом'як. Большая синагога в Стрые

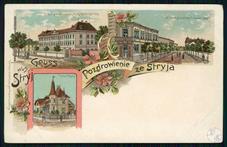

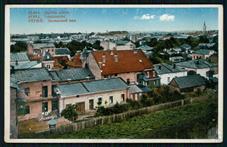

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Stryj

- Juedisches Muzeum Berlin

- Wikipedia. Стрийська громада

- Jewish encyclopedia World ORT

- Jewish encyclopedia of Brockhaus & Efron

- Virtual Shtetl. Stryi

Photo:

- Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Stryy New Jewish Cemetery, Stryy Old Jewish Cemetery

- Vladimir Levin, Boris Khaimovich, Eva Maria Kraiss: Center for Jewish art. Stryi (Стрий)

- Сергій Хом'як. Большая синагога в Стрые

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Stryj

- Juedisches Muzeum Berlin

- Wikipedia. Стрийська громада

Stryy, or Stryi (Ukrainian: Стрий) is a city in Lviv region.

Stryy was mentioned for the first time in 1385. Already then its territory was incorporated in the Kingdom of Poland after the decline of Ruthenian Kingdom.

In 1431 it was given the Magdeburg Rights, and it was located in the Ruthenian Voivodeship, which from the 14th century until 1772 was a part of Poland. The city was governed by the local magistrate headed by a burgomaster.

Stryy was mentioned for the first time in 1385. Already then its territory was incorporated in the Kingdom of Poland after the decline of Ruthenian Kingdom.

In 1431 it was given the Magdeburg Rights, and it was located in the Ruthenian Voivodeship, which from the 14th century until 1772 was a part of Poland. The city was governed by the local magistrate headed by a burgomaster.

Jews began to settle in Stryi at the beginning of the 16th century. The locality was situated on the trade route between Poland and Hungary. In 1576, King Stefan Batory issued the official permit for Jews to settle in the area, guaranteeing them the same rights as those protecting Christians. Throughout the next century, the Town Council tried to undermine this decision, but all subsequent Polish kings confirmed the privileges, admonishing Christian merchants not to engage in any hostile activities.

The Jewish community in Stryi was established not later than the end of the 16th century. It initially belonged to the Przemyśl District of the Council of Four Lands.

In 1634, it was granted permission to build a synagogue and a set up a cemetery.

In the middle of the 17th century, King Jan Kazimierz, finally yielding to the Town Council, issued a decree banning Jews from settling in Stryi. Nonetheless, the royal district governor by the name of Koniecpolski not only did not enforce it, but actively sought to increase the Jewish population of the town.

In the years 1652-1670, Jews bought 11 houses in Stryi, and in 1660 they built a synagogue.

In 1662, there were 70 Jews living in the town (5% of the population).

The Jewish community in Stryi was established not later than the end of the 16th century. It initially belonged to the Przemyśl District of the Council of Four Lands.

In 1634, it was granted permission to build a synagogue and a set up a cemetery.

In the middle of the 17th century, King Jan Kazimierz, finally yielding to the Town Council, issued a decree banning Jews from settling in Stryi. Nonetheless, the royal district governor by the name of Koniecpolski not only did not enforce it, but actively sought to increase the Jewish population of the town.

In the years 1652-1670, Jews bought 11 houses in Stryi, and in 1660 they built a synagogue.

In 1662, there were 70 Jews living in the town (5% of the population).

|

|

|

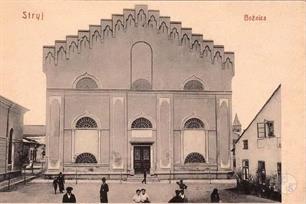

| Stryy synagogue on the postcard of beginning XX century. | Left - another synagogue | Synagogue in Stryy, 1997 |

|

|

|

| Synagogue in Stryy, 2021 | Adress - street Mikhnovskoho, 5 |

|

|

|

| Synagogue of Meer Shulim, 1997 | Synagogue of Meer Shulim, 2011 | Synagogue of Meer Shulim located immediately near the Old synagogue |

In 1663, the successor of Koniecpolski and the future king, Jan Sobieski, announced that Jews would retain all the rights granted in the past. He also banned the Town Council from settling matters concerning municipal taxes without the participation of two representatives of the Jewish community.

In 1670, in an attempt to resolve the long-lasting conflict, the authorities sent a special commission to Stryi. It concluded that all privileges of Jews, including those of 1634, would remain valid, but that the Jewish population should pay taxes at the equal level as the rest of the population.

In 1676, Sobieski ordered that trade fair days be held in Stryi not only on Saturdays but also on Tuesdays.

In 1689, Jews were given permission to build another wooden synagogue.

In 1696, the Town Council and the Jewish community finally entered an agreement: there was to be only one trading day per week – Friday.

In 1697, Catholic priests from Stryi accused Jews of stealing objects of worship from the church. The investigation lasted until 1708, but the claims turned out to be unfounded.

In 1670, in an attempt to resolve the long-lasting conflict, the authorities sent a special commission to Stryi. It concluded that all privileges of Jews, including those of 1634, would remain valid, but that the Jewish population should pay taxes at the equal level as the rest of the population.

In 1676, Sobieski ordered that trade fair days be held in Stryi not only on Saturdays but also on Tuesdays.

In 1689, Jews were given permission to build another wooden synagogue.

In 1696, the Town Council and the Jewish community finally entered an agreement: there was to be only one trading day per week – Friday.

In 1697, Catholic priests from Stryi accused Jews of stealing objects of worship from the church. The investigation lasted until 1708, but the claims turned out to be unfounded.

In the 1820s, various restrictions were imposed on Jews involved in wine trade and the lease of homesteads. This resulted in the significant increase in the number of Jewish craftsmen, tailors, bakers, woodworkers, gunmetal and tin platers, and fur dealers.

In the 1870s, Jewish entrepreneurs founded a foundry, a wood processing yard, a soap factory and a matchmaking plant.

A Jewish hospital was opened in the town in 1873.

In 1891, the “Adamat Israel” Zionist Society was formed, and in 1893 – the first Jewish trade union.

In 1910, the Jewish population of Stryi had 12,023 members.

The two lower secondary schools in the town were attended by 447 Jewish children (37.8% of the pupils. In the first school - in 1910, 217 Jews of 710 of the total number of students, in the second school - 230 of 472). About 10 Jewish teachers worked there, among them are Dr. Binenstok, the author of "Das Judentum in Heines Dichtungen".

In 1910, a Jewish boarding school was opened for 30 students.

In the 1870s, Jewish entrepreneurs founded a foundry, a wood processing yard, a soap factory and a matchmaking plant.

A Jewish hospital was opened in the town in 1873.

In 1891, the “Adamat Israel” Zionist Society was formed, and in 1893 – the first Jewish trade union.

In 1910, the Jewish population of Stryi had 12,023 members.

The two lower secondary schools in the town were attended by 447 Jewish children (37.8% of the pupils. In the first school - in 1910, 217 Jews of 710 of the total number of students, in the second school - 230 of 472). About 10 Jewish teachers worked there, among them are Dr. Binenstok, the author of "Das Judentum in Heines Dichtungen".

In 1910, a Jewish boarding school was opened for 30 students.

|

|

|

| Former Jewish school on str. Shevchenko, 70 | Jewish houses on Mikhnovskoho and Hoholya streets, 2015 | Jewish houses on Nebesnoyi Sotni street, 2015 |

|

|

|

| House of Jewish droctor Fichner, 1916 | Villa of Jew Lauterbakh, 1916 | This villa has been preserved and is located at 85/1 Shevchenko Street |

During World War I, Stryi temporarily came under Russian occupation (1914-1915). This period was marked by the harassment and persecution of Jews. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian state, Jewish organisations created a self-defence unit of 40 people. There was a Jewish National Assembly in Stryi, headed by E. Byk and M. Binensztok; the Jidysze Fołkssztyme newspaper was being published.

In the years 1919-1939, Stryi belonged to Poland.

In 1921, there were 10,988 Jews living in the town (about 40% of the total population); in 1931 – 10,869, in 1939 – about 12,000.

At the beginning of the 1920s, several mayors of the town were Jews.

In the interwar period, branches of all Zionist parties and the Agudath were active in Stryi. There was a vocational school funded by the Joint, as well as two other Jewish schools (also of the Tarbut network).

In September 1939, the town was occupied by the Red Army and incorporated into the Soviet Union. New authorities abolished Jewish organisations, and arrested and deported many prominent members of the Jewish community.

In 1941, the security services of the USSR murdered or incarcerated several local Jewish communist officials.

In the years 1919-1939, Stryi belonged to Poland.

In 1921, there were 10,988 Jews living in the town (about 40% of the total population); in 1931 – 10,869, in 1939 – about 12,000.

At the beginning of the 1920s, several mayors of the town were Jews.

In the interwar period, branches of all Zionist parties and the Agudath were active in Stryi. There was a vocational school funded by the Joint, as well as two other Jewish schools (also of the Tarbut network).

In September 1939, the town was occupied by the Red Army and incorporated into the Soviet Union. New authorities abolished Jewish organisations, and arrested and deported many prominent members of the Jewish community.

In 1941, the security services of the USSR murdered or incarcerated several local Jewish communist officials.

On 2 July 1941, German troops entered Stryi. Soon afterwards, the Ukrainians from OUN-UPA murdered several Jews. The occupation authorities established the Judenrat in the town.

The first mass executions of Jews took place in the forest near Stryi in November 1941. About 1,200 people were murdered that day. The next massacre was carried out in May 1942. In the years 1941-1942, hundreds of young Jews were deported to forced labour camps; many of them died there from exhaustion.

On 1 September 1942, Germans took several thousand people from Stryi to the death camp in Bełżec, followed by another 2,000 on 17-18 September of the same year.

On 1 December 1942, the remaining Jews from Stryi were placed in the ghetto.

In February 1943, Germans shot about 2,000 inhabitants of the Jewish district.

In May 1943, ca. 1,000 were killed at the municipal cemetery.

The ghetto was liquidated in June 1943. Homes were burned so that there would be no possibility of hiding. Those imprisoned in labour camps were killed one month later.

In August 1943, the German authorities announced that Stryi was Judenrein (“cleansed of Jews”; however, many Jews were found and shot over the following months). Only a few survived until August 1944, when the town was taken over by the Red Army.

After the war, the Jewish community was not revived.

The first mass executions of Jews took place in the forest near Stryi in November 1941. About 1,200 people were murdered that day. The next massacre was carried out in May 1942. In the years 1941-1942, hundreds of young Jews were deported to forced labour camps; many of them died there from exhaustion.

On 1 September 1942, Germans took several thousand people from Stryi to the death camp in Bełżec, followed by another 2,000 on 17-18 September of the same year.

On 1 December 1942, the remaining Jews from Stryi were placed in the ghetto.

In February 1943, Germans shot about 2,000 inhabitants of the Jewish district.

In May 1943, ca. 1,000 were killed at the municipal cemetery.

The ghetto was liquidated in June 1943. Homes were burned so that there would be no possibility of hiding. Those imprisoned in labour camps were killed one month later.

In August 1943, the German authorities announced that Stryi was Judenrein (“cleansed of Jews”; however, many Jews were found and shot over the following months). Only a few survived until August 1944, when the town was taken over by the Red Army.

After the war, the Jewish community was not revived.

A lot of old architecture has been preserved in the city.

In 1765, 1,727 Jews lived in the community encompassing Stryi and its surroundings.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the main source of their income was trade, both wholesale (imports of horses and wines from Hungary, exports of bulls, cereals and salt) and retail. In some cases, commercial transactions were conducted on a really large scale.

In the years 1701-1704, Samuel Chaimowicz sold up to 18,000 barrels of salt per year. Other sources of income of the community were: brewing, leasing of farms and mills, financial activity (taking out loans with commercial tariffs as collaterals). The number of craftsmen (jewellers, blacksmiths, and tailors) was relatively small.

In 1772, after the First Partition of Poland, Stryi found itself under the Austrian rule.

In 1795, 444 Jewish families lived in the town and its nine suburbs.

From the end of the 18th century, Jews were strongly influenced by Hasidism. This was despite the fact that Arie Lejb Heller (1745-1813?), the rabbi of the town in the years 1788-1813 and the founder of a large yeshiva, was an outright opponent of the Hasidim.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the main source of their income was trade, both wholesale (imports of horses and wines from Hungary, exports of bulls, cereals and salt) and retail. In some cases, commercial transactions were conducted on a really large scale.

In the years 1701-1704, Samuel Chaimowicz sold up to 18,000 barrels of salt per year. Other sources of income of the community were: brewing, leasing of farms and mills, financial activity (taking out loans with commercial tariffs as collaterals). The number of craftsmen (jewellers, blacksmiths, and tailors) was relatively small.

In 1772, after the First Partition of Poland, Stryi found itself under the Austrian rule.

In 1795, 444 Jewish families lived in the town and its nine suburbs.

From the end of the 18th century, Jews were strongly influenced by Hasidism. This was despite the fact that Arie Lejb Heller (1745-1813?), the rabbi of the town in the years 1788-1813 and the founder of a large yeshiva, was an outright opponent of the Hasidim.

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate