Rava-Ruska

Lviv district, Lviv region

Year - Total Population - Jews

1880 - 6,468 - 3,878

1890 - 7,475 - 4,406

1900 - 8,927 - 5,098

1910 - 10,775 - 6,112

1921 - 8,970 - 5,048

1931 - 11,146 - 5,688

1880 - 6,468 - 3,878

1890 - 7,475 - 4,406

1900 - 8,927 - 5,098

1910 - 10,775 - 6,112

1921 - 8,970 - 5,048

1931 - 11,146 - 5,688

Sources:

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II, page 498-503, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. Translated by Shlomo Sneh, JewishGen, Inc.

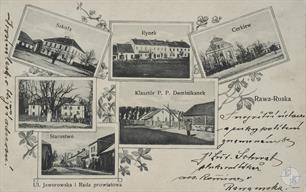

Photo:

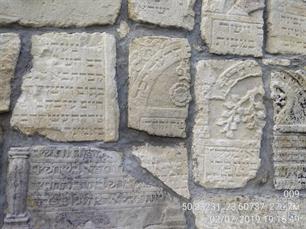

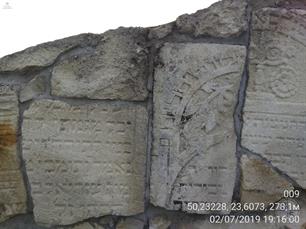

- Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Rava-Ruska New Jewish Cemetery

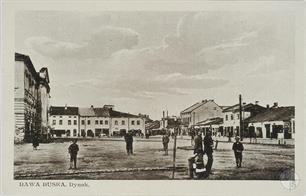

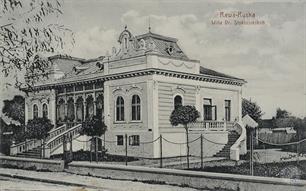

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Rawa-Ruska

- Tomek Wisniewski, Bagnowka. Rawa Ruska

- Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II, page 498-503, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. Translated by Shlomo Sneh, JewishGen, Inc.

Photo:

- Jewish Cemeteries Initiative. Rava-Ruska New Jewish Cemetery

- Biblioteka Narodowa Polona. Rawa-Ruska

- Tomek Wisniewski, Bagnowka. Rawa Ruska

Jewish Settlement, from the beginning of settlement until 1919

Rava-Ruska (ukr. Rava-Ruska, Рава-Руська) was established in 1664 as a private city, owned by the nobility. In 1698 the Polish king and the Russian Czar Peter the Great conferred there, and decided to wage war on Sweden. In 1716 the countries warring over the domination of Poland came to an agreement at Rava Ruska, and King August II continued to reign.

Large fires broke out in 1862 and 1894, and hundreds of buildings burned down. The city was greatly damaged during the Russian occupation (1914-1915).

It appears that the first Jews arrived in Rava-Ruska when it was established. During the years 1629-1643 there were 25 Jewish houses in Rava-Ruska.

In the era of the Polish Kingdom the Jews of Rava-Ruska made their living through trade, distilled liquor, sales, and some artisanship.

The rights of the Jews were limited in the eighteenth century as a result of the conflicts between Jews and other townspeople. The Jews were prohibited from employing Christian servants, and Christians were not permitted to eat at Jewish tables.

The district governor did not activate the prohibition against making and selling bromfn (a kind of strong alcoholic drink) in Rava- Ruska at the start of the Austrian regime. Heavy taxes were levied on the Jews of Rava-Ruska, as on the rest of Galician Jews. Mainly they suffered from the tax on candles.

The city and its Jewish and non-Jewish population developed and grew during the second half of the nineteenth century, especially at the end of the century, since the train from Lvov to Warsaw passed through Rava-Ruska.

The Great Fire of 1884 destroyed 234 of 243 Jewish houses.

The main source of income for the Jews in this era was trade, especially in eggs, which were exported. This business employed merchants, sorters, carpenters (those who made boxes), and those who produced lime for egg storage. Jews also dealt in other agricultural products, which they exported abroad. Some of the Jews continued to run their saloons, engage in retail trade, and peddle. The Jews worked in all aspects of artisanship, and were especially noted as furriers and hatters. Some Jews made their living as construction workers. Eight of the 100 construction workers in Rava-Ruska were Jews.

Jews owned some factories that also employed other members of the community. Among the factories was one for artistic stone tableware. This factory was established in the middle of the nineteenth century. Its products were sold all over the empire, but stopped production when people bought ceramic tableware. Another factory produced oil, which was renowned all over Galicia, and was owned by Hershel Monk. The products of the factory were very highly esteemed, and were also strictly kosher. Jews worked at home making hog bristle brushes, and three workshops had 40 apprentices, all of them Jews. The broom and straw basket industry in Rava-Ruska also employed a number of contractors. One of them had 22 workers; 12 had salaries, and the rest were apprentices.

In the second half of the nineteenth century there were a few Jewish estate owners, and many Jewish tenants. At the beginning of the twentieth century there was one Jewish lawyer and one Jewish doctor. Toward the beginning of the First World War, the number of Jewish professionals grew. In about 1910 a Jewish bank was started, which in 1913 distributed loans to: 269 merchants, 127 artisans, 6 farmers, 8 professionals, and 36 others. At the end of the nineteenth century Rava-Ruska Jews began to emigrate abroad. In 1910 an organization of Rava-Ruska emigrants was established in New York, called Merchaot Hevrat Bnai Levi Yitzhak- Anshei Rava Ruska.

Until the eighteenth century the Rava-Ruska community was under the control of the Julke community, which chose its rabbis. The first rabbi of Rava-Ruska known to us is Rabbi Naftali Hertz, son of Moshe, from Brody. He lived in Rava-Ruska from 1735 to 1742, and afterwards moved to Julke. Rabbi Yechiel Mordechai Altschuler succeeded him. Together with his father, David, who lived in Prague they wrote popular commentary on the prophets and biblical texts, Metzudat David and Metzudat Zion.

Rabbi Yitzhak Shimon, son of Rabbi Moshe, was the rabbi of Rava-Ruska during the years 1785-1790. The first rabbi independent of the Julke community was Rabbi Menachem Mendel during the years 1790-1810. Rabbi Natan Dov Halevi Stern, son of Rabbi Joseph Yuzba, succeeded him. In the second half of the nineteenth century there were two famous scholars in Rava-Ruska. There was Rabbi Shlomo Kluger, famous as the Magid of Brody, and Rabbi Zacharia, one of the disciples of the Seer of Lublin. Rabbi Levi Itzhak Shor, author of Ateret Tiferet, published by his grandson in 1912, was the Rava-Ruska rabbi in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. The organization of Rava-Ruska emigrants in New York is named after him. Rabbi Levi Itzhak died in 1877. Rabbi Dov Berish HaKohen Rappaport succeeded him, a Zanz Hassid and friend of the Belz Admor. Rabbi Dov Berish was famous because of his book Merchaot Derech HaMelech about the Rambam. When he died in 1907 his sickly grandson, Rabbi Joseph Haim, succeeded him, and he actually functioned until the First World War.

The majority of Rava-Ruska Jews had been Hassidim since the beginning of the nineteenth century. When the Belz court was established, almost all of them came under its wing. However, there were a few Maskilim in Rava- Ruska. Two of them were very well known. One was Yitzhak Herter, the Maskil and writer, known from the era of the Haskala. He was a physician in Rava-Ruska for a few years, and saved many of its inhabitants during the 1831 plague. Rabbi Avram Goldberg, a citizen of the city, and one of its wealthy men, was a disciple and friend of Rabbi Nachman Krochmal (RENAK). Their attitude to Hassidim was completely negative. In 1848, two years before his death, Avram Goldberg published a book in Lvov called Masar Tzafon Im Maase Rokeach. The book ends with a sentence that mocks the Belz dynasty.

There was no continuity to the ideas of Avram Goldberg until the twentieth century, for the Belz Hasidim dominated the community of Rava Ruska.

There were many synagogues in Rava-Ruska, named according to their location, such as the Synagogue on the Sands.

Rava-Ruska (ukr. Rava-Ruska, Рава-Руська) was established in 1664 as a private city, owned by the nobility. In 1698 the Polish king and the Russian Czar Peter the Great conferred there, and decided to wage war on Sweden. In 1716 the countries warring over the domination of Poland came to an agreement at Rava Ruska, and King August II continued to reign.

Large fires broke out in 1862 and 1894, and hundreds of buildings burned down. The city was greatly damaged during the Russian occupation (1914-1915).

It appears that the first Jews arrived in Rava-Ruska when it was established. During the years 1629-1643 there were 25 Jewish houses in Rava-Ruska.

In the era of the Polish Kingdom the Jews of Rava-Ruska made their living through trade, distilled liquor, sales, and some artisanship.

The rights of the Jews were limited in the eighteenth century as a result of the conflicts between Jews and other townspeople. The Jews were prohibited from employing Christian servants, and Christians were not permitted to eat at Jewish tables.

The district governor did not activate the prohibition against making and selling bromfn (a kind of strong alcoholic drink) in Rava- Ruska at the start of the Austrian regime. Heavy taxes were levied on the Jews of Rava-Ruska, as on the rest of Galician Jews. Mainly they suffered from the tax on candles.

The city and its Jewish and non-Jewish population developed and grew during the second half of the nineteenth century, especially at the end of the century, since the train from Lvov to Warsaw passed through Rava-Ruska.

The Great Fire of 1884 destroyed 234 of 243 Jewish houses.

The main source of income for the Jews in this era was trade, especially in eggs, which were exported. This business employed merchants, sorters, carpenters (those who made boxes), and those who produced lime for egg storage. Jews also dealt in other agricultural products, which they exported abroad. Some of the Jews continued to run their saloons, engage in retail trade, and peddle. The Jews worked in all aspects of artisanship, and were especially noted as furriers and hatters. Some Jews made their living as construction workers. Eight of the 100 construction workers in Rava-Ruska were Jews.

Jews owned some factories that also employed other members of the community. Among the factories was one for artistic stone tableware. This factory was established in the middle of the nineteenth century. Its products were sold all over the empire, but stopped production when people bought ceramic tableware. Another factory produced oil, which was renowned all over Galicia, and was owned by Hershel Monk. The products of the factory were very highly esteemed, and were also strictly kosher. Jews worked at home making hog bristle brushes, and three workshops had 40 apprentices, all of them Jews. The broom and straw basket industry in Rava-Ruska also employed a number of contractors. One of them had 22 workers; 12 had salaries, and the rest were apprentices.

In the second half of the nineteenth century there were a few Jewish estate owners, and many Jewish tenants. At the beginning of the twentieth century there was one Jewish lawyer and one Jewish doctor. Toward the beginning of the First World War, the number of Jewish professionals grew. In about 1910 a Jewish bank was started, which in 1913 distributed loans to: 269 merchants, 127 artisans, 6 farmers, 8 professionals, and 36 others. At the end of the nineteenth century Rava-Ruska Jews began to emigrate abroad. In 1910 an organization of Rava-Ruska emigrants was established in New York, called Merchaot Hevrat Bnai Levi Yitzhak- Anshei Rava Ruska.

Until the eighteenth century the Rava-Ruska community was under the control of the Julke community, which chose its rabbis. The first rabbi of Rava-Ruska known to us is Rabbi Naftali Hertz, son of Moshe, from Brody. He lived in Rava-Ruska from 1735 to 1742, and afterwards moved to Julke. Rabbi Yechiel Mordechai Altschuler succeeded him. Together with his father, David, who lived in Prague they wrote popular commentary on the prophets and biblical texts, Metzudat David and Metzudat Zion.

Rabbi Yitzhak Shimon, son of Rabbi Moshe, was the rabbi of Rava-Ruska during the years 1785-1790. The first rabbi independent of the Julke community was Rabbi Menachem Mendel during the years 1790-1810. Rabbi Natan Dov Halevi Stern, son of Rabbi Joseph Yuzba, succeeded him. In the second half of the nineteenth century there were two famous scholars in Rava-Ruska. There was Rabbi Shlomo Kluger, famous as the Magid of Brody, and Rabbi Zacharia, one of the disciples of the Seer of Lublin. Rabbi Levi Itzhak Shor, author of Ateret Tiferet, published by his grandson in 1912, was the Rava-Ruska rabbi in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. The organization of Rava-Ruska emigrants in New York is named after him. Rabbi Levi Itzhak died in 1877. Rabbi Dov Berish HaKohen Rappaport succeeded him, a Zanz Hassid and friend of the Belz Admor. Rabbi Dov Berish was famous because of his book Merchaot Derech HaMelech about the Rambam. When he died in 1907 his sickly grandson, Rabbi Joseph Haim, succeeded him, and he actually functioned until the First World War.

The majority of Rava-Ruska Jews had been Hassidim since the beginning of the nineteenth century. When the Belz court was established, almost all of them came under its wing. However, there were a few Maskilim in Rava- Ruska. Two of them were very well known. One was Yitzhak Herter, the Maskil and writer, known from the era of the Haskala. He was a physician in Rava-Ruska for a few years, and saved many of its inhabitants during the 1831 plague. Rabbi Avram Goldberg, a citizen of the city, and one of its wealthy men, was a disciple and friend of Rabbi Nachman Krochmal (RENAK). Their attitude to Hassidim was completely negative. In 1848, two years before his death, Avram Goldberg published a book in Lvov called Masar Tzafon Im Maase Rokeach. The book ends with a sentence that mocks the Belz dynasty.

There was no continuity to the ideas of Avram Goldberg until the twentieth century, for the Belz Hasidim dominated the community of Rava Ruska.

There were many synagogues in Rava-Ruska, named according to their location, such as the Synagogue on the Sands.

Between the Two World Wars

The number of Jews in Rava-Ruska diminished by about a thousand at the end of the First World War. Incomplete data shows the following occupations for the Jews of Rava-Ruska in 1921: 80 saloonkeepers, 400 small businessmen, 300 grain traders, 300 wholesale traders, 100 peddling in the villages, 400 artisans, and 55 employed as porters and carters. In 1919 four soup kitchens that served free lunches were established with the support of the Polish authorities, and the Joint. Two were for Jews. Seventy percent of the Jewish population (including 1,800 children) was given food by the Joint, and 1,300 received clothing.

The part of the Jewish Quarter in which the poor people lived caught on fire in the summer of 1923. 278 Jews, 90 of them under the age of 14, remained without a place to live. Another big fire broke out in 1932. Sixty-two families, only one of them Christian, lost all their property in it.

The number of Jews in Rava-Ruska diminished by about a thousand at the end of the First World War. Incomplete data shows the following occupations for the Jews of Rava-Ruska in 1921: 80 saloonkeepers, 400 small businessmen, 300 grain traders, 300 wholesale traders, 100 peddling in the villages, 400 artisans, and 55 employed as porters and carters. In 1919 four soup kitchens that served free lunches were established with the support of the Polish authorities, and the Joint. Two were for Jews. Seventy percent of the Jewish population (including 1,800 children) was given food by the Joint, and 1,300 received clothing.

The part of the Jewish Quarter in which the poor people lived caught on fire in the summer of 1923. 278 Jews, 90 of them under the age of 14, remained without a place to live. Another big fire broke out in 1932. Sixty-two families, only one of them Christian, lost all their property in it.

In the first city elections of 1928 there was one list, a 3-group bloc. According to agreements, Jews got 22 representatives; Poles got 20, and Ukrainians 6.

The Jewish list consisted of 3 Belzers, 4 assimilationists, 5 Yad Haruzim representatives, 3 Agudat Yisroel members, 3 Hitachdut members, and 4 from a united list of General Zionists and the Mizrachi.

In the 1933 elections, in which the total number of Jewish city council members was 24, the Belzers gained 6 seats, and Bund one. Later one member of the Bund moved to Hitachdut.

Until 1928 Belz Hassidim and sympathizers dominated the Kehilla. But in the 1928 elections the Zionist numbers strengthened, and gained 7 of the 12 seats. The Belz Hassidim persisted, and bribed one of the Zionist representatives into becoming a member of their faction. He could not stand the repercussions of his actions, and tried to commit suicide. He resigned, and another Zionist replaced him. The Zionists now controlled the Kehilla, and their leader, Dr. Yosef Mendel, was elected head. He held this function until the beginning of the Second World War.

Rabbi Yizhak Nachum Twersky, son-in-law of the Belzer Admor, was nominated in 1927 as Rabbi of Rava-Ruska. In this period these Admors held their courts in Rava-Ruska: Rabbi Yerachmiel Moshe Rappaport, Rabbi Arieh Leibish, son of Rabbi Yoshua Rokach of Belz, who had previously lived in Magierov, and Rabbi Shalom Rokach, ex-rabbi of Nemirov.

At this time the majority of Jewish children studied in Jewish government public schools, called Shabasofska. A complementary Hebrew school, established in Rava- Ruska in 1922, suffered greatly from the opposition of Belz Hassidim. They declared that anyone sending his children to this school would not be called up to the Torah, and would be prohibited from standing on the pulpit when saying kaddish. Despite this boycott the school was established, and about 60 children attended. In 1931 a kindergarten attached to this school was established, including about 40 tots. Agudat Yisroel established a complementary Jewish girls' school, Beis Yakov.

Each party active in Rava- Ruska established a drama club. HaTikva, the cultural union of the General Zionists, founded the first one. There also were drama clubs that belonged to Hitachdut, the Revisionists, and the Bund. Even Agudat Yisroel in Rava- Ruska had a dramatic circle of its own. As there was no Jewish public building in Rava- Ruska, the orphanage became a theater and center for other pursuits.

The biggest Jewish library was owned by the Bund. Its activities included general education programs, which helped many poor community members to better themselves. A Jewish sports union, Hapoel, was established in Rava-Ruska in the early 1930's.

In 1922 some new recruits rioted in the streets. One Jewish woman was killed, and some Jews were injured. The police restored order, and many of the rioters were jailed. In the mid 1930's sometimes robbers, and others with clearly anti-Semitic motives, attacked many Jewish villagers around Rava-Ruska. Four out of six members of a Jewish family were murdered in a nearby village in 1935. A Jew who testified against a Christian who stole from him was murdered that year. Near the city an estate with a Jewish owner was burned in 1936. On Yom Kippur of 1938 six houses of Jews were burned in a village near Rava-Ruska, and the families remained without shelter.

The Jewish list consisted of 3 Belzers, 4 assimilationists, 5 Yad Haruzim representatives, 3 Agudat Yisroel members, 3 Hitachdut members, and 4 from a united list of General Zionists and the Mizrachi.

In the 1933 elections, in which the total number of Jewish city council members was 24, the Belzers gained 6 seats, and Bund one. Later one member of the Bund moved to Hitachdut.

Until 1928 Belz Hassidim and sympathizers dominated the Kehilla. But in the 1928 elections the Zionist numbers strengthened, and gained 7 of the 12 seats. The Belz Hassidim persisted, and bribed one of the Zionist representatives into becoming a member of their faction. He could not stand the repercussions of his actions, and tried to commit suicide. He resigned, and another Zionist replaced him. The Zionists now controlled the Kehilla, and their leader, Dr. Yosef Mendel, was elected head. He held this function until the beginning of the Second World War.

Rabbi Yizhak Nachum Twersky, son-in-law of the Belzer Admor, was nominated in 1927 as Rabbi of Rava-Ruska. In this period these Admors held their courts in Rava-Ruska: Rabbi Yerachmiel Moshe Rappaport, Rabbi Arieh Leibish, son of Rabbi Yoshua Rokach of Belz, who had previously lived in Magierov, and Rabbi Shalom Rokach, ex-rabbi of Nemirov.

At this time the majority of Jewish children studied in Jewish government public schools, called Shabasofska. A complementary Hebrew school, established in Rava- Ruska in 1922, suffered greatly from the opposition of Belz Hassidim. They declared that anyone sending his children to this school would not be called up to the Torah, and would be prohibited from standing on the pulpit when saying kaddish. Despite this boycott the school was established, and about 60 children attended. In 1931 a kindergarten attached to this school was established, including about 40 tots. Agudat Yisroel established a complementary Jewish girls' school, Beis Yakov.

Each party active in Rava- Ruska established a drama club. HaTikva, the cultural union of the General Zionists, founded the first one. There also were drama clubs that belonged to Hitachdut, the Revisionists, and the Bund. Even Agudat Yisroel in Rava- Ruska had a dramatic circle of its own. As there was no Jewish public building in Rava- Ruska, the orphanage became a theater and center for other pursuits.

The biggest Jewish library was owned by the Bund. Its activities included general education programs, which helped many poor community members to better themselves. A Jewish sports union, Hapoel, was established in Rava-Ruska in the early 1930's.

In 1922 some new recruits rioted in the streets. One Jewish woman was killed, and some Jews were injured. The police restored order, and many of the rioters were jailed. In the mid 1930's sometimes robbers, and others with clearly anti-Semitic motives, attacked many Jewish villagers around Rava-Ruska. Four out of six members of a Jewish family were murdered in a nearby village in 1935. A Jew who testified against a Christian who stole from him was murdered that year. Near the city an estate with a Jewish owner was burned in 1936. On Yom Kippur of 1938 six houses of Jews were burned in a village near Rava-Ruska, and the families remained without shelter.

The Second World War

Jewish war refugees who made their way towards the Romanian border arrived in Rava-Ruska at the start of the war in 1939. Some of them remained in the city, and were helped by the local Jewish community. On September 10, 1939, the Germans occupied Rava-Ruska. Decrees were published immediately about wearing Jewish stars, limitations on movements, and forced labor. One local Jew was killed for being on the street during the hours of curfew. German soldiers also broke into synagogues, and desecrated Torah scrolls. The Germans left the city after the agreement with the Soviets. Red Army units entered on Sept. 24, 1939. The arrival was generally received with a feeling of relief because it ended the German occupation, but very quickly there were changes that affected a large part of the Jewish population. Jewish organizations were disbanded, community institutions, and many synagogues closed because of the imposition of high taxes. According to the nationalization policy, many enterprises owned by Jews were nationalized.

Quite a few Jewish youths became members of the Soviet –organized militia, but their numbers diminished in 1940. Some Jewish families were imprisoned in March 1940 on economic grounds, and were deported into the interior of the Soviet Union. Many Jewish refugees from Western Poland who found a haven in Rava-Ruska were imprisoned and deported in May and June of 1940.

Routes out of the city between Germany and the Soviet Union were quickly closed at the beginning of the war, because of its proximity to the border, and Jewish attempts to flee eastward failed.

On June 28, 1941 the Germans occupied Rava-Ruska. At the beginning of July 1941 the Ukrainian militia captured about 100 Jews, according to a list the prepared immediately. All were executed by shooting in the nearby Wolkowitza forest. Many of those murdered were the intelligentsia.

In July 1941 the Germans ordered the establishment of a Judenrat. Schweitzer, a Jew from Germany, was put at the head. At the beginning the dominant figure was Yosef Mendel, the leading personality of the Kehilla. He had great influence on the members of the council, which did its best to lighten the suffering of Rava-Ruska Jews. When his opposition to German policy aroused antagonism, he was jailed, and disappeared. There was permanent tension between Schweitzer, the head of the Judenrat, and Mendel, because Schweitzer tended to obey all German orders. The Judenrat was ordered to take a census of the Jewish population, to supply compulsory labor, and give the Germans valuables. By August 1941 the Judenrat had to pay 5,000 rubles.

Aside from fulfilling German demands, the Judenrat gave material aid and medical help to the needy. It established a soup kitchen that distributed 100 bowls of watery soup a day to the hungry, and also organized a Jewish hospital. A staff of physicians and nurses gave devoted help, although limited by lack of means, to many. In one of the Aktions of 1942, Schweitzer was taken for extermination. His successors were Vatenberg, a pharmacist, and Herman Lippel. The suffering of the Rava- Ruska Kehilla increased in the autumn of 1941 and during the winter of 1942. The Germans demanded greater numbers of Jews for compulsory work. An additional contribution of two kilos of gold was levied at the end of 1941. The Jews also were ordered to relinquish all the fur clothing they owned. Hunger and disease caused many deaths. On January 17, 1942, the Germans ordered 250 Jews to a work camp in the area. The Jews tried to evade going to the camp, but the Germans prevailed, and the Judenrat was compelled to fulfill the quota.

The first mass Aktion was on March 20, 1942. German and Ukrainian police units arrived in the town, and began kidnapping Jews in the streets and from houses. Some of those kidnapped were taken out of the groups that were taken for forced labor. About 1,500 were sent to the Belzec extermination camp. Some were murdered in the city, and others in the forest nearby. The day after the Aktion, the Germans ordered the destruction of the old Jewish cemetery in the center of the town. Jews were ordered to take out grave stones, plow the area, and pave a road using the broken grave stones.

The Jews were concentrated in a special quarter in the spring of 1942. There they suffered from overcrowding, and a typhoid epidemic broke out.

Another Aktion began on July 29, 1942, and it continued for a few days.

Many were murdered in the town during the Aktion. Jews from surrounding towns were also brought to Rava-Ruska, and sent with the locals to extermination camps. About 800 from Niemirow were sent to Belzec with more than 1,200 Jews from Rava-Ruska. Germans and theirs aides made special efforts in this Aktion to discover hiding places in the Jewish quarter. Some of those they found were murdered on the spot. About 30 people were murdered after they refused to enter the train carriages. About 60 of those expelled from Rava-Ruska in this Aktion jumped from the train that took them to Belzec, and returned to the city injured and fatigued. Many were killed when they tried to jump.

Every day during the summer months of 1942 trains passed through Rava-Ruska taking Jews from Eastern Galicia to the extermination camp of Belzec. One estimate is that 500 of those who jumped from the trains arrived in Rava-Ruska. They received help from the remnants of the local community before they continued their return to their home towns. The local Judenrat also helped those who fled, some injured. The Jews of Rava- Ruska were in danger of receiving severe collective punishment, because of this activity.

In truth the Jews of Rava-Ruska had already surmised that something terrible was happening at the Belzec camp, which was not far away, although they did not know the precise facts.

About 250 Jews from Potylich, and others from Niemirow, Magierow, and Uhnow were expelled to Rava-Ruska at the beginning of September 1942. The ghetto was closed at the beginning of December 1942, and from this time the Jews could not leave.

All old and infirm of the ghetto were concentrated on December 7, 1942. Many of them died in the train carriages on the way to Belzec, and others were murdered in a forest near the town. The liquidation of the ghetto began on December 9, 1942.

German and Ukrainian police put the remnants of the community on trucks. They took them to Shidietsky Forest, shot them, and threw the bodies into two pits that had been prepared ahead of time. Only about 300 Jews, who gathered and arranged the Jewish property remaining after the last Aktion, lived in the ghetto by the end of December 1942. The number of these Jews dwindled until there were 60, because the Germans transported the rest to the labor camps in the area. A labor camp was also established in Rava-Ruska near the Rata River. Some dozens of the last Jews of Rava- Ruska and the vicinity were concentrated there, among them the last Jews of Mosty Velikye.

The Germans were informed that about 250 Jews had succeeded in hiding in the ghetto area or with Christian friends. To find them, the Germans announced that everyone, even children, who would leave his hiding place, would be transported to a labor camp, and be unharmed. Because of the difficult conditions in hiding places, and a feeling that people could not hide in them for a long time, some dozen Jews decided to emerge and enter the local labor camp. But in June 1943 the Germans murdered the majority of the people in the camp, especially women and children.

Only a few succeeded in finding hiding places with Christian friends, or in bunkers in the nearby forest, until the liberation of the town by the Soviets on July 20, 1944.

Jewish life in Rava-Ruska was never reestablished after the war.

Jewish war refugees who made their way towards the Romanian border arrived in Rava-Ruska at the start of the war in 1939. Some of them remained in the city, and were helped by the local Jewish community. On September 10, 1939, the Germans occupied Rava-Ruska. Decrees were published immediately about wearing Jewish stars, limitations on movements, and forced labor. One local Jew was killed for being on the street during the hours of curfew. German soldiers also broke into synagogues, and desecrated Torah scrolls. The Germans left the city after the agreement with the Soviets. Red Army units entered on Sept. 24, 1939. The arrival was generally received with a feeling of relief because it ended the German occupation, but very quickly there were changes that affected a large part of the Jewish population. Jewish organizations were disbanded, community institutions, and many synagogues closed because of the imposition of high taxes. According to the nationalization policy, many enterprises owned by Jews were nationalized.

Quite a few Jewish youths became members of the Soviet –organized militia, but their numbers diminished in 1940. Some Jewish families were imprisoned in March 1940 on economic grounds, and were deported into the interior of the Soviet Union. Many Jewish refugees from Western Poland who found a haven in Rava-Ruska were imprisoned and deported in May and June of 1940.

Routes out of the city between Germany and the Soviet Union were quickly closed at the beginning of the war, because of its proximity to the border, and Jewish attempts to flee eastward failed.

On June 28, 1941 the Germans occupied Rava-Ruska. At the beginning of July 1941 the Ukrainian militia captured about 100 Jews, according to a list the prepared immediately. All were executed by shooting in the nearby Wolkowitza forest. Many of those murdered were the intelligentsia.

In July 1941 the Germans ordered the establishment of a Judenrat. Schweitzer, a Jew from Germany, was put at the head. At the beginning the dominant figure was Yosef Mendel, the leading personality of the Kehilla. He had great influence on the members of the council, which did its best to lighten the suffering of Rava-Ruska Jews. When his opposition to German policy aroused antagonism, he was jailed, and disappeared. There was permanent tension between Schweitzer, the head of the Judenrat, and Mendel, because Schweitzer tended to obey all German orders. The Judenrat was ordered to take a census of the Jewish population, to supply compulsory labor, and give the Germans valuables. By August 1941 the Judenrat had to pay 5,000 rubles.

Aside from fulfilling German demands, the Judenrat gave material aid and medical help to the needy. It established a soup kitchen that distributed 100 bowls of watery soup a day to the hungry, and also organized a Jewish hospital. A staff of physicians and nurses gave devoted help, although limited by lack of means, to many. In one of the Aktions of 1942, Schweitzer was taken for extermination. His successors were Vatenberg, a pharmacist, and Herman Lippel. The suffering of the Rava- Ruska Kehilla increased in the autumn of 1941 and during the winter of 1942. The Germans demanded greater numbers of Jews for compulsory work. An additional contribution of two kilos of gold was levied at the end of 1941. The Jews also were ordered to relinquish all the fur clothing they owned. Hunger and disease caused many deaths. On January 17, 1942, the Germans ordered 250 Jews to a work camp in the area. The Jews tried to evade going to the camp, but the Germans prevailed, and the Judenrat was compelled to fulfill the quota.

The first mass Aktion was on March 20, 1942. German and Ukrainian police units arrived in the town, and began kidnapping Jews in the streets and from houses. Some of those kidnapped were taken out of the groups that were taken for forced labor. About 1,500 were sent to the Belzec extermination camp. Some were murdered in the city, and others in the forest nearby. The day after the Aktion, the Germans ordered the destruction of the old Jewish cemetery in the center of the town. Jews were ordered to take out grave stones, plow the area, and pave a road using the broken grave stones.

The Jews were concentrated in a special quarter in the spring of 1942. There they suffered from overcrowding, and a typhoid epidemic broke out.

Another Aktion began on July 29, 1942, and it continued for a few days.

Many were murdered in the town during the Aktion. Jews from surrounding towns were also brought to Rava-Ruska, and sent with the locals to extermination camps. About 800 from Niemirow were sent to Belzec with more than 1,200 Jews from Rava-Ruska. Germans and theirs aides made special efforts in this Aktion to discover hiding places in the Jewish quarter. Some of those they found were murdered on the spot. About 30 people were murdered after they refused to enter the train carriages. About 60 of those expelled from Rava-Ruska in this Aktion jumped from the train that took them to Belzec, and returned to the city injured and fatigued. Many were killed when they tried to jump.

Every day during the summer months of 1942 trains passed through Rava-Ruska taking Jews from Eastern Galicia to the extermination camp of Belzec. One estimate is that 500 of those who jumped from the trains arrived in Rava-Ruska. They received help from the remnants of the local community before they continued their return to their home towns. The local Judenrat also helped those who fled, some injured. The Jews of Rava- Ruska were in danger of receiving severe collective punishment, because of this activity.

In truth the Jews of Rava-Ruska had already surmised that something terrible was happening at the Belzec camp, which was not far away, although they did not know the precise facts.

About 250 Jews from Potylich, and others from Niemirow, Magierow, and Uhnow were expelled to Rava-Ruska at the beginning of September 1942. The ghetto was closed at the beginning of December 1942, and from this time the Jews could not leave.

All old and infirm of the ghetto were concentrated on December 7, 1942. Many of them died in the train carriages on the way to Belzec, and others were murdered in a forest near the town. The liquidation of the ghetto began on December 9, 1942.

German and Ukrainian police put the remnants of the community on trucks. They took them to Shidietsky Forest, shot them, and threw the bodies into two pits that had been prepared ahead of time. Only about 300 Jews, who gathered and arranged the Jewish property remaining after the last Aktion, lived in the ghetto by the end of December 1942. The number of these Jews dwindled until there were 60, because the Germans transported the rest to the labor camps in the area. A labor camp was also established in Rava-Ruska near the Rata River. Some dozens of the last Jews of Rava- Ruska and the vicinity were concentrated there, among them the last Jews of Mosty Velikye.

The Germans were informed that about 250 Jews had succeeded in hiding in the ghetto area or with Christian friends. To find them, the Germans announced that everyone, even children, who would leave his hiding place, would be transported to a labor camp, and be unharmed. Because of the difficult conditions in hiding places, and a feeling that people could not hide in them for a long time, some dozen Jews decided to emerge and enter the local labor camp. But in June 1943 the Germans murdered the majority of the people in the camp, especially women and children.

Only a few succeeded in finding hiding places with Christian friends, or in bunkers in the nearby forest, until the liberation of the town by the Soviets on July 20, 1944.

Jewish life in Rava-Ruska was never reestablished after the war.

|

|

| Jewish neighborhood. On the right - 3-floors Great Synagogue, on the left - Aizerner kloyz | Destroyed kloyz |

The Jews of Rava-Ruska never succeeded in electing a Jewish mayor, during all the years they were a majority of its citizens. This was in contrast to elsewhere in Galicia.

As in many other Galician communities, Herz Homberg opened a school for Jewish children in 1788. The school was closed, like others of the sort, in 1806. In 1892 a Jewish school was opened in Rava-Ruska, established by Baron Hirsch. It had 200 pupils in 1898. In 1900 the school gained government accreditation. In 1902 the school moved to its own building, and existed until the First World War. The school also gave courses for adults, with about 60 pupils.

In 1908 a group of Jewish workers established a branch of the Jewish Socialist Party – Z.P.S. The first Zionist organization, Hatikva, was established in 1910, but the community's official leaders persecuted it. The Belzer Hassidim were not opposed to any method of ill-treating Zionists, and they denounced them to the authorities.

The city is close to the Russian border, and for this reason the Jews of Rava- Ruska did not succeed in fleeing into Austria during the First World War. When the armies of Austria recaptured the city in the summer of 1915, epidemics erupted: first cholera, and then typhoid. Many residents died of these plagues, Jews among them, because of overcrowding in apartments, and lack of hospitals and physicians.

After Austria's surrender in November 1918, Rava-Ruska was within the borders of the Western Ukrainian Republic for a short time. The Polish army besieged the city, and there also were battles in the town. At the end of 1918 the Polish captured Rava-Ruska, and the front passed some kilometers away. The Polish soldiers, especially those of General Haller, tortured the Jews, and pulled off or snipped their beards. The distinguished Margaliot family, one of the most distinguished in the city, was accused of shooting some Polish soldiers, who claimed that they had been shot and injured by them. The accused were moved to Lublin, and had a court martial, but were found innocent when it was revealed that the accusation was a libel. During the battle with Ukrainians, one Jewish baker hid an injured Polish officer. The baker was awarded a medal in 1927 from the Polish government.

As in many other Galician communities, Herz Homberg opened a school for Jewish children in 1788. The school was closed, like others of the sort, in 1806. In 1892 a Jewish school was opened in Rava-Ruska, established by Baron Hirsch. It had 200 pupils in 1898. In 1900 the school gained government accreditation. In 1902 the school moved to its own building, and existed until the First World War. The school also gave courses for adults, with about 60 pupils.

In 1908 a group of Jewish workers established a branch of the Jewish Socialist Party – Z.P.S. The first Zionist organization, Hatikva, was established in 1910, but the community's official leaders persecuted it. The Belzer Hassidim were not opposed to any method of ill-treating Zionists, and they denounced them to the authorities.

The city is close to the Russian border, and for this reason the Jews of Rava- Ruska did not succeed in fleeing into Austria during the First World War. When the armies of Austria recaptured the city in the summer of 1915, epidemics erupted: first cholera, and then typhoid. Many residents died of these plagues, Jews among them, because of overcrowding in apartments, and lack of hospitals and physicians.

After Austria's surrender in November 1918, Rava-Ruska was within the borders of the Western Ukrainian Republic for a short time. The Polish army besieged the city, and there also were battles in the town. At the end of 1918 the Polish captured Rava-Ruska, and the front passed some kilometers away. The Polish soldiers, especially those of General Haller, tortured the Jews, and pulled off or snipped their beards. The distinguished Margaliot family, one of the most distinguished in the city, was accused of shooting some Polish soldiers, who claimed that they had been shot and injured by them. The accused were moved to Lublin, and had a court martial, but were found innocent when it was revealed that the accusation was a libel. During the battle with Ukrainians, one Jewish baker hid an injured Polish officer. The baker was awarded a medal in 1927 from the Polish government.

Jews developed the production of furs between the two world wars. This branch included fur coats, both inexpensive fur coats for farmers and luxury products, which were sold all over Poland. Small contractors supplied raw materials, and sold the finished products, which were made at home. There was also a furriers' cooperative (apparently people who worked at home). The Jewish fur makers organized Yad Harutzim in this period, and businessmen started the Union of Merchants and Factory Owners. The merchants renewed the bank that had been established by the JCA, and named it the Cooperative Bank. Of the 232 shareholders of the bank were 154 small merchants, 41artisans, 16 industrialists and major merchants, 5 professionals, 4 farmers, plus 12 others. In 1937 the shareholders were 35 farmers, 171 big merchants and industrialists, 54 artisans, 4 clerks, and 34 others. In same year the bank circulated about 2.5 million zlotys. There was also a Free Loan Fund that annually distributed about 60 loans, or about 5,000 zlotys.

The majority of Rava-Ruska Jews was Belz Hassidim and their sympathizers until the First World War. At the end of the war the Socialists, Zionists, and supporters of Agudat Yisroel appeared. The most important movement that challenged the Belz domination of the community was Zionism and its factions. Dr. Yosef Mendel, who was born in Lvov and settled in Rava-Ruska in 1917, was a major influence for change.

He was one of the initiators of the Jewish cooperative bank, and also represented his city in the central body of the cooperative in Lvov and Warsaw. In 1924 the Hitachadut and the Mizrachi were established. Dr. Shimon Federbush, a member of the Polish Sejm, and the Chief Rabbi of Finland during the years 1931-1940, was among those who established Mizrachi. The Revisionist Party was established in 1928. The first Zionist youth organization in Rava-Ruska was HaShomer, which was active for a short time at the end of the First World War. HaNoar Zioni-Achva was established in 1925, then Betar and Akiva in 1930. Gordonia, established in 1925, had the strongest youth organization in Rava-Ruska. Hashomer Hazair was established in 1937. In the early 1930's there were Hanoar Zioni training farms in Rava-Ruska. Although there was strong opposition by the Belz Hassidim, a branch of Agudat Yisroel, and with it Agudat Yisroel youth, male and female, was organized in Rava-Ruska in 1927 or 1928. Some members of this organization went to training farms, and made aliyah to Palestine. The Bund, and the children's organization SKIF was connected to the ZPS. Some members of the Bund affiliated with the illegal Communist Party.

Belz Hassidim also functioned in Rava-Ruska as a regular party. The few assimilationists in the city supported them.

The majority of Rava-Ruska Jews was Belz Hassidim and their sympathizers until the First World War. At the end of the war the Socialists, Zionists, and supporters of Agudat Yisroel appeared. The most important movement that challenged the Belz domination of the community was Zionism and its factions. Dr. Yosef Mendel, who was born in Lvov and settled in Rava-Ruska in 1917, was a major influence for change.

He was one of the initiators of the Jewish cooperative bank, and also represented his city in the central body of the cooperative in Lvov and Warsaw. In 1924 the Hitachadut and the Mizrachi were established. Dr. Shimon Federbush, a member of the Polish Sejm, and the Chief Rabbi of Finland during the years 1931-1940, was among those who established Mizrachi. The Revisionist Party was established in 1928. The first Zionist youth organization in Rava-Ruska was HaShomer, which was active for a short time at the end of the First World War. HaNoar Zioni-Achva was established in 1925, then Betar and Akiva in 1930. Gordonia, established in 1925, had the strongest youth organization in Rava-Ruska. Hashomer Hazair was established in 1937. In the early 1930's there were Hanoar Zioni training farms in Rava-Ruska. Although there was strong opposition by the Belz Hassidim, a branch of Agudat Yisroel, and with it Agudat Yisroel youth, male and female, was organized in Rava-Ruska in 1927 or 1928. Some members of this organization went to training farms, and made aliyah to Palestine. The Bund, and the children's organization SKIF was connected to the ZPS. Some members of the Bund affiliated with the illegal Communist Party.

Belz Hassidim also functioned in Rava-Ruska as a regular party. The few assimilationists in the city supported them.

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine