Zastavna

The oldest written mention of Zastavna dates back to 1589. The first settlers came to Zastavna from the north in the XII century.

In the Galicia-Volyn chronicle, the road from Vasilev, the then large trade center on the Dniester, to Chernivtsi, is mentioned. In the most successful for crossing the river Sovitsu there was an "outpost" - something like a checkpoint, where the duty was taken from merchants. This river, which in those days was full of water, has turned into our days in a small stream.

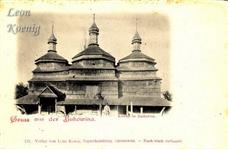

In the 19 - beginning 20 c. Zastavna - in the province of Bukovina as part of Austria-Hungary. In 1918-40 years. - as part of Romania, since 1940 - the Ukrainian SSR.

In 1774 there were 17 Jews living in Zastavna,

in 1776 - 33,

in 1808 - 100 Jewish families,

in 1910, there were 418 Jews,

in the 1930's. - 629 Jews (12.3%).

The first Jews, immigrants from Galicia, settled in Zastavna in the early 18th century. In 1810, all Jews engaged in trade were evicted from the city. Only two families, engaged in agriculture, were allowed to stay.

After the liberalization of the "Jewish policy" of the Austrian authorities in the 2-nd part of 19th century Jews again began to settle in Zastavna. In 1870 a cemetery was founded, on which the Jews of all the surrounding villages were buried. There were 3 synagogues, mikvah, Talmud-torah. There was a rabbi and a shokhet.

In 1891, the Zastavny community, whose council consisted of 13 people, included Jews from 29 small settlements in the Nistru region.

In the Galicia-Volyn chronicle, the road from Vasilev, the then large trade center on the Dniester, to Chernivtsi, is mentioned. In the most successful for crossing the river Sovitsu there was an "outpost" - something like a checkpoint, where the duty was taken from merchants. This river, which in those days was full of water, has turned into our days in a small stream.

In the 19 - beginning 20 c. Zastavna - in the province of Bukovina as part of Austria-Hungary. In 1918-40 years. - as part of Romania, since 1940 - the Ukrainian SSR.

In 1774 there were 17 Jews living in Zastavna,

in 1776 - 33,

in 1808 - 100 Jewish families,

in 1910, there were 418 Jews,

in the 1930's. - 629 Jews (12.3%).

The first Jews, immigrants from Galicia, settled in Zastavna in the early 18th century. In 1810, all Jews engaged in trade were evicted from the city. Only two families, engaged in agriculture, were allowed to stay.

After the liberalization of the "Jewish policy" of the Austrian authorities in the 2-nd part of 19th century Jews again began to settle in Zastavna. In 1870 a cemetery was founded, on which the Jews of all the surrounding villages were buried. There were 3 synagogues, mikvah, Talmud-torah. There was a rabbi and a shokhet.

In 1891, the Zastavny community, whose council consisted of 13 people, included Jews from 29 small settlements in the Nistru region.

The rapid rise and the economic blossoming of the municipality of Zastawna in Northern Bukovina was undeniably due to its Jewish inhabitants. Twenty-nine surrounding villages in which Jews lived and worked belonged to the Jewish community of Zastawna. Numerically, they were in the minority, the majority of the inhabitants being Ruthene, who were almost without exception occupied in farming, but thanks to their economic position, the Jews were very important.

Almost all the large estates were in Jewish hands. The large sugar factory belonged to Marcu and Dr. Max Fischer, the alcohol factory and motor mill, incidentally, the only large industrial concern similarly belonged to Jews. Among the most notable of the estate owners was Hersch Weissglas who had been distinguished with the title, “Advisor to the Kaiser,” and his son Siegmund Weissglas, who was the first president of the Regional Zionist organization in Chernivtsi. To them belonged the estates Zastawna, Lenlioutz, Willawcze Bila, Odaja, Scherschiziowce, Sloboda Zloty, Plitinitza, Stinka and Zidiwaka Dolina, which later came into the possession of the niece Nora Gutherz.

Other estate owners were Mordko Korn, who owned the estates Szypenitz, Alt und Neu Werenczanka, Perzelowka and Draczinetz; Marcu and Dr. Max Fischer, the owners of six estates; Kisiel Socal: Emanuel Baumann; Janku Fisher; Bernhard Korn; Leon Korn; the scholarly rabbi's son Babad; Simche Bartfeld; Aron Hager and Mendl Jekeles.

In addition to the Jews who owned large estates, there were many whose profession was large scale farming, among others, the author of this essay. When one considers that based on Austrian law, the land owners had many prerogatives, it is easy to understand the superior political position of the Jews in the Zastawna district. For a long time, the Talmud scholar, and Zionist, Berl Waldmann, whose son, Dr. Moses Waldmann, a childhood friend of the author of this report was press chief at the first Zionist congress in Basel. served as estate area administrator.

Siegmund Weissglass was the first and only Jewish mayor of Zastawna. In most cities in which a Ruthene was at the top of the city administration, the deputy was a Jew. In Zastawna, for many years, the deputy mayor was druggist Emil Schecht, in Zwiniacze, it was the alcohol distiller, Elias Gottesmann who was known to the Ruthene farmers as “Wajko Elio” (little uncle Elias), in Kadobestie, the land owner and Propinationspaechter Abraham Sternberg, the father of the Revisionist leader, Dr. Benzion Sternberg. In Wassileu, Mendl Teitler who had been awarded the silver service cross with a crown; in Pohorloutz, the land owner Hersch Weisinger; in Okna, the Propinationspaechter Itzig Gaertner; in Kissileu, the land owner and Propinationspaechter Ksak Bickel, the father of the New York journalist, Dr. Shlomo Bickel. Almost 75% of state employees were Jewish.

To name some: Government Commissioner Robert Schletter who functioned as a district captain, a unique position for a Jew at that time, the Presidential Secretary Sigfried Weintraub, Regional Court Counsel Dr. Leo Rosen, also the only Jewish court director, the Presidential Secretary Siegmund Stenzler, Inspector of the Court Office Tamler, Land Register Administrator Zwerling, Court Officials Bibring and Lapajowker, Court Clerks Wender, Kirschner, Singer and Halpern, Officers of the Court Leo Warmflasch and Finkelthal, Surveyor Schottenfeld, Evidence Registration Inspector Josef Stadler, Surveyor Sponder, Police Commander Salo Rosenberg, who became postmaster in Boroutz, Tax Administrator Gredinger, the Tax Official Jaslowitz, Adjuncts Lublin, Lilian and Eisenfraft as well as Postmaster Augenblick.

The war hero, Hersch Frischling (Chrupki) who won the Great Gold War Medal in the Bosnian campaign, was highly respected in the town.

Almost all the large estates were in Jewish hands. The large sugar factory belonged to Marcu and Dr. Max Fischer, the alcohol factory and motor mill, incidentally, the only large industrial concern similarly belonged to Jews. Among the most notable of the estate owners was Hersch Weissglas who had been distinguished with the title, “Advisor to the Kaiser,” and his son Siegmund Weissglas, who was the first president of the Regional Zionist organization in Chernivtsi. To them belonged the estates Zastawna, Lenlioutz, Willawcze Bila, Odaja, Scherschiziowce, Sloboda Zloty, Plitinitza, Stinka and Zidiwaka Dolina, which later came into the possession of the niece Nora Gutherz.

Other estate owners were Mordko Korn, who owned the estates Szypenitz, Alt und Neu Werenczanka, Perzelowka and Draczinetz; Marcu and Dr. Max Fischer, the owners of six estates; Kisiel Socal: Emanuel Baumann; Janku Fisher; Bernhard Korn; Leon Korn; the scholarly rabbi's son Babad; Simche Bartfeld; Aron Hager and Mendl Jekeles.

In addition to the Jews who owned large estates, there were many whose profession was large scale farming, among others, the author of this essay. When one considers that based on Austrian law, the land owners had many prerogatives, it is easy to understand the superior political position of the Jews in the Zastawna district. For a long time, the Talmud scholar, and Zionist, Berl Waldmann, whose son, Dr. Moses Waldmann, a childhood friend of the author of this report was press chief at the first Zionist congress in Basel. served as estate area administrator.

Siegmund Weissglass was the first and only Jewish mayor of Zastawna. In most cities in which a Ruthene was at the top of the city administration, the deputy was a Jew. In Zastawna, for many years, the deputy mayor was druggist Emil Schecht, in Zwiniacze, it was the alcohol distiller, Elias Gottesmann who was known to the Ruthene farmers as “Wajko Elio” (little uncle Elias), in Kadobestie, the land owner and Propinationspaechter Abraham Sternberg, the father of the Revisionist leader, Dr. Benzion Sternberg. In Wassileu, Mendl Teitler who had been awarded the silver service cross with a crown; in Pohorloutz, the land owner Hersch Weisinger; in Okna, the Propinationspaechter Itzig Gaertner; in Kissileu, the land owner and Propinationspaechter Ksak Bickel, the father of the New York journalist, Dr. Shlomo Bickel. Almost 75% of state employees were Jewish.

To name some: Government Commissioner Robert Schletter who functioned as a district captain, a unique position for a Jew at that time, the Presidential Secretary Sigfried Weintraub, Regional Court Counsel Dr. Leo Rosen, also the only Jewish court director, the Presidential Secretary Siegmund Stenzler, Inspector of the Court Office Tamler, Land Register Administrator Zwerling, Court Officials Bibring and Lapajowker, Court Clerks Wender, Kirschner, Singer and Halpern, Officers of the Court Leo Warmflasch and Finkelthal, Surveyor Schottenfeld, Evidence Registration Inspector Josef Stadler, Surveyor Sponder, Police Commander Salo Rosenberg, who became postmaster in Boroutz, Tax Administrator Gredinger, the Tax Official Jaslowitz, Adjuncts Lublin, Lilian and Eisenfraft as well as Postmaster Augenblick.

The war hero, Hersch Frischling (Chrupki) who won the Great Gold War Medal in the Bosnian campaign, was highly respected in the town.

The community was the most important influence in the political life of the Jews of the district. For the election of the community president, the position of the Zionist Association, led by the pharmacist, Emil Schecht was influential. The Zionist Siegmund Weissglas, who Herzel repeatedly mentioned flatteringly in his diary, running against the estate owner, of Doroschoutz, Nathan Goldenberg, was elected president His private secretary was Jakob Stenzler. There was a “Frauenhilfsverein” (ladies aid organization) in the town, lead alternately by the ladies Rosa Safrin, Bronela Neumann, Mina Stenzler, Pepi Schecht, Rosa Diwer and Anna Silberbusch which concerned itself with the construction and maintenance of a ritual bath. Mrs. Mina Stenzler died in Israel at the age of 103.

There was also a competently run WIZO organization. The members were: Dora Stenzler, Selma Schecht, Cecilia Schuster, Malcia Tamler, Ottilie Segall, Bitia Mauler, Marie Diwer, the Jaegendorf sisters, Pepi and Toni Neufeld, Fanny Warmflasch, Majka Grossmann and Nethi Diwer.

In 1905, the Zionist organization sent its members, Dr. Kinsbrunner and Herzberg from Chernivtsi as well as Jakob Stenzler from Zastawna to the nearby Galician city of Zaleszczyki in order to campaign for the Reichsrath candidacy of Dr. N. Birnbaum. His opponent was the Polish Graf Mojsey, who was supported by “Anti-Zionists” under the leadership of Mayor Dr. Isidor Blutreich. The Zionist delegates couldn't do anything against the open election fraud and cheating carried on by the Polish Schliachta. They were arrested and had to be satisfied with the fact that they were soon released from jail.

After the outbreak of the war in 1914, a large part of the population fled to Vienna. Many of the refugees were later sent by the Vienna relief organizations to Bruenn. In 1917, when the enemy was driven out of Bukovina, many returned to their earlier homes and the rest returned after the fall of the monarchy, although, the occupation of the land by Romania during the period that they were away, did not make for a joyous homecoming.

At the beginning of the Romanian administration, the community retained a certain autonomy within the framework of its statutes. Community presidents at that time were the pharmacist, E. Schecht and Dr. Tamler, who along with Jakob Stenzler, the court official and the respected Zionist Leon Warmflasch the community secretary were all instrumental in building the temple. The following president, Jakob Stenzler was elected to four, four years terms, almost unanimously. He enjoyed the active support of the Zionist pharmacist Schecht, Dr. Emil Diwer, the following president of the Zionist Association and Natan and Wolf Jaegendorf. Thus, the community remained under Zionist leadership. Yearly contributions for the K.H. and the K.K.L. were a constant item in the budget of the community. The community's new statute which the president, J. Stenzler had developed with the changed situation in mind, was approved thanks to the Minister Dr. Theophil Saucine-Saveanu who was a friend of the Jews.

There was also a competently run WIZO organization. The members were: Dora Stenzler, Selma Schecht, Cecilia Schuster, Malcia Tamler, Ottilie Segall, Bitia Mauler, Marie Diwer, the Jaegendorf sisters, Pepi and Toni Neufeld, Fanny Warmflasch, Majka Grossmann and Nethi Diwer.

In 1905, the Zionist organization sent its members, Dr. Kinsbrunner and Herzberg from Chernivtsi as well as Jakob Stenzler from Zastawna to the nearby Galician city of Zaleszczyki in order to campaign for the Reichsrath candidacy of Dr. N. Birnbaum. His opponent was the Polish Graf Mojsey, who was supported by “Anti-Zionists” under the leadership of Mayor Dr. Isidor Blutreich. The Zionist delegates couldn't do anything against the open election fraud and cheating carried on by the Polish Schliachta. They were arrested and had to be satisfied with the fact that they were soon released from jail.

After the outbreak of the war in 1914, a large part of the population fled to Vienna. Many of the refugees were later sent by the Vienna relief organizations to Bruenn. In 1917, when the enemy was driven out of Bukovina, many returned to their earlier homes and the rest returned after the fall of the monarchy, although, the occupation of the land by Romania during the period that they were away, did not make for a joyous homecoming.

At the beginning of the Romanian administration, the community retained a certain autonomy within the framework of its statutes. Community presidents at that time were the pharmacist, E. Schecht and Dr. Tamler, who along with Jakob Stenzler, the court official and the respected Zionist Leon Warmflasch the community secretary were all instrumental in building the temple. The following president, Jakob Stenzler was elected to four, four years terms, almost unanimously. He enjoyed the active support of the Zionist pharmacist Schecht, Dr. Emil Diwer, the following president of the Zionist Association and Natan and Wolf Jaegendorf. Thus, the community remained under Zionist leadership. Yearly contributions for the K.H. and the K.K.L. were a constant item in the budget of the community. The community's new statute which the president, J. Stenzler had developed with the changed situation in mind, was approved thanks to the Minister Dr. Theophil Saucine-Saveanu who was a friend of the Jews.

A Hebrew school was founded by Emil Schecht, Dr. Tamler, Jakob Stenzler, Abraham Grossmann, David Segal, Leon Picker, Wolf Tennenblatt, Naziu Warmflasch and Siegmund Hacker and especially Nathan and Wolf Jaegendorf. The teachers were Professors Chaim Grossmann and Jampolski.

After Wolf Jaegendorf left the community, the administration was in the hands of his successor, Abraham Grossmann. The community subsidized the Talmud Torah Association created through the efforts of Wolf Jaegendorf, Benjamin Stenzler and Abraham Grossmann and also the Jabotinsky Association, under the chairmanship of its founder, David Schuster. The former led a model farm on which hundreds of youths completed the Hachschara in order to emigrate to Eretz Israel after a successful education (The Russians sent him to Siberia in 1941, from where he returned after 20 years). The community rabbi, Berl Schapira and especially Jakob Gottesmann was well liked because of his scholarship and his unassuming nature.

In June 1941, German and Rumanian troops entered the Zastavna. The Jews of the town and the surrounding villages were imprisoned in the ghetto.

In October 1941, all Jews were sent to Transnistria and distributed there in the camps and ghettos of various cities (Obodovka, Bershad, Tulchin, Yampol). Most of them died, about 10% of Jews are left alive.

After 1945, about 40 Jews returned to Zastavna; but after a while almost all went to Rumunia, and from there - to Israel. Three synagogues were given under grain barns, a cinema opened in the Great Synagogue building.

In the 1960s. in Zastavna lived several Jews who moved from the eastern regions of Ukraine. Today (2016) there are no Jews here.

The Jewish cemetery was demolished, a restaurant was placed on its territory. Behind the building of the restaurant a small area was selected, where the preserved matzevs were buried, and a monument was erected from above. There is no direct access there, but the owner of the restaurant held us and showed us everything.

When we were looking for a cemetery, the local resident showed us the way. According to her, the territory of the cemetery was given to new owners with observance of all necessary rituals, the priest came and consecrated. All according Feng Shui...

After Wolf Jaegendorf left the community, the administration was in the hands of his successor, Abraham Grossmann. The community subsidized the Talmud Torah Association created through the efforts of Wolf Jaegendorf, Benjamin Stenzler and Abraham Grossmann and also the Jabotinsky Association, under the chairmanship of its founder, David Schuster. The former led a model farm on which hundreds of youths completed the Hachschara in order to emigrate to Eretz Israel after a successful education (The Russians sent him to Siberia in 1941, from where he returned after 20 years). The community rabbi, Berl Schapira and especially Jakob Gottesmann was well liked because of his scholarship and his unassuming nature.

In June 1941, German and Rumanian troops entered the Zastavna. The Jews of the town and the surrounding villages were imprisoned in the ghetto.

In October 1941, all Jews were sent to Transnistria and distributed there in the camps and ghettos of various cities (Obodovka, Bershad, Tulchin, Yampol). Most of them died, about 10% of Jews are left alive.

After 1945, about 40 Jews returned to Zastavna; but after a while almost all went to Rumunia, and from there - to Israel. Three synagogues were given under grain barns, a cinema opened in the Great Synagogue building.

In the 1960s. in Zastavna lived several Jews who moved from the eastern regions of Ukraine. Today (2016) there are no Jews here.

The Jewish cemetery was demolished, a restaurant was placed on its territory. Behind the building of the restaurant a small area was selected, where the preserved matzevs were buried, and a monument was erected from above. There is no direct access there, but the owner of the restaurant held us and showed us everything.

When we were looking for a cemetery, the local resident showed us the way. According to her, the territory of the cemetery was given to new owners with observance of all necessary rituals, the priest came and consecrated. All according Feng Shui...

Sources:

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia. Translated from Russian by Eugene Snaider

- Jakob Stenzler. Zastawna / Geschichte der Juden in der Bukowina (History of the Jews in the Bukowina), vol. II. Edited by Hugo Gold. Tel Aviv: Olamenu, 1962. Translated from German by Jerome Silverbush z”l, JewishGen, Inc

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

- Postcard collection of Eduard Turkevych

- David Shay, Wikipedia. Zastavna memorial at Holon Cemetery

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia. Translated from Russian by Eugene Snaider

- Jakob Stenzler. Zastawna / Geschichte der Juden in der Bukowina (History of the Jews in the Bukowina), vol. II. Edited by Hugo Gold. Tel Aviv: Olamenu, 1962. Translated from German by Jerome Silverbush z”l, JewishGen, Inc

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

- Postcard collection of Eduard Turkevych

- David Shay, Wikipedia. Zastavna memorial at Holon Cemetery

Chernivtsi district, Chernivtsi region

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine