Storozhynets

Storozhynets was first mentioned in the letter of the Moldovan ruler Roman II dated February 18, 1448 as a guard post on Siret, which probably gave the name to the city. Archaeological research conducted in the middle of the 20th century indicates that the settlement existed here already in the XIV century, since the emergence of the Moldavian principality. The second time Storozhynets was mentioned in 1476 as the property of the Moldavian feudal lord Todorah Sorocanu. According to the literacy of the Moldovan ruler Stephen III the Great, dated 1490, at the end of the XV century Storozhynets was part of the Suceava region and had its own church parish.

In 1880, 1601 Jew lived in Storozhynets (33%),

in 1890 - 1993 (35.3%),

in 1910 - 4832,

in 1924 - 2600 (26%),

In 1930 - 2480 Jews.

In 1880, 1601 Jew lived in Storozhynets (33%),

in 1890 - 1993 (35.3%),

in 1910 - 4832,

in 1924 - 2600 (26%),

In 1930 - 2480 Jews.

Chernivtsi district, Chernivtsi region

The period of Jewish immigration can only be approximated. According to the date on a wooden Mazewa (tombstone), whose letters are in relief, we can conclude that around the year 1800 there were already Jews living in Storozynetz. From that time the family name Blukop (later Blaukopf) was handed down. It is known that Moses Blaukopf (1777 - 1864) was an accountant with the Jewish company Barber & Co., which was the general collector of all state revenues for the whole Bukowina. He emigrated in 1847 to Eretz Israel, where he died in Safed.

One of his descendants was Fishel Blaukopf, whose son Izchak Josef Blaukopf, born in Storozynetz on January 14, 1858, was working as CEO at the office of the Deputy Mayor of Czernowitz, Dr. Alois Ritter (Knight) von Tabora, between the years 1877 and 1898. Later, he was an official of the Municipal Council until 1928. He was also the editor of the Czernowitz Municipal Council's newspaper, founded by Josef Wiedmann. Shortly before his death (1939), he composed a family chronicle, containing some very rare historical and cultural descriptions.

In 1828 the Jew Markus Anhauch, a merchant from Lvov, settled in Storozynetz. His son, Salomon Anhauch, was the first Jew in Storozynetz to be granted, by imperial decree of the December 2, 1865, the right to possess unlimited agricultural properties and urban-Christian real estate.

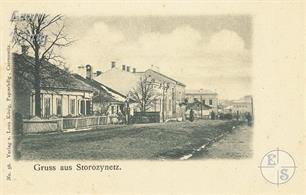

Since the Jews of Storozynetz preferred to have their houses, stores and workshops in the center of the locality, the latter was called the “Jewish Shtetl”. That they reached prosperity was to the explicit merit of the Jewish mayor, Dr. Isidor Katz.

Not just the commerce, but also the crafts and the intellectual professions were in Jewish hands. Tailors, cobblers, carpenters, and harness-makers were 99% Jewish. The three tanneries belonged to Jews, and mills, sawmills, and alcohol breweries were rented by Jews. Like in every “Jewish Shtetl”, here were also Jewish owners of wagons, carriers and cargo-porters. The Jews had the best relations with the other inhabitants until the occupation of the Bukovina by Roumania.

As to the Jews of the Storozynetz district, their situation was the same as in the town of Storozynetz. There were no villages where Jews were not lessees of farms or of public houses. Many agricultural properties were rented and managed by Jews. The lumber trade, which was blooming in this district, was also in Jewish hands. In the rural localities the Jews also had good relationships with the other inhabitants. Entirely Roumanian or Ruthenian communities often elected Jews as their mayors, e.g. in Moldauisch-Banilla, Czudyn, Cziresch and Korczeschti. In almost all communities, Jews were the community secretaries.

The man, to whom - as above mentioned - the powerful situation of the Jews is to be credited, was Dr. Isidor Katz, who settled around 1890 as a lawyer in Storozynetz, designated at this time as a “market community”. The community-manager was the Jewish pharmacist Philipp Fuellenbaum. The locality, already inhabited by many Jews, suffered most of all from poor sanitary conditions. The Jewish apartments consisted almost everywhere of small, single-level houses of one room, or rarely of two rooms and a kitchen, where huge families lived through the day and slept at night. Although the Jewish housewife was anyway attentive to maintaining her home very clean, dust from the streets and dirt were a real obstacle to this goal. Because of that, epidemics occurred very often and the death rate in this part of Storozynetz, where the Jews lived as in a Ghetto, was quite high.

The pharmacist Fuellenbaum left for Czernowitz and Dr. Katz was then elected Mayor. After he took over the community management, he hired the medical Dr. Sussmann Kupferberg as community Medical Doctor. The latter's first assignment was to improve the sanitary conditions in common places, courtyards and especially the buildings in the Jewish sector of the locality. Roads and paths were cleaned by community employees, and particular attention was directed to sanitary objects (private and common latrines). The lighting of the streets was expanded and, to provide more security to the inhabitants, a community police force was assembled.

The whole aspect of the “market community” got, thanks to these measures, a favorable change. The managers of the different government offices located in Storozynetz fully supported the efforts of Dr. Isidor Katz. An energetic influx of Jewish merchants, craftsmen, medical doctors and lawyers, as well as government employees, among them Jews as well, increased the number of the inhabitants.

One of his descendants was Fishel Blaukopf, whose son Izchak Josef Blaukopf, born in Storozynetz on January 14, 1858, was working as CEO at the office of the Deputy Mayor of Czernowitz, Dr. Alois Ritter (Knight) von Tabora, between the years 1877 and 1898. Later, he was an official of the Municipal Council until 1928. He was also the editor of the Czernowitz Municipal Council's newspaper, founded by Josef Wiedmann. Shortly before his death (1939), he composed a family chronicle, containing some very rare historical and cultural descriptions.

In 1828 the Jew Markus Anhauch, a merchant from Lvov, settled in Storozynetz. His son, Salomon Anhauch, was the first Jew in Storozynetz to be granted, by imperial decree of the December 2, 1865, the right to possess unlimited agricultural properties and urban-Christian real estate.

Since the Jews of Storozynetz preferred to have their houses, stores and workshops in the center of the locality, the latter was called the “Jewish Shtetl”. That they reached prosperity was to the explicit merit of the Jewish mayor, Dr. Isidor Katz.

Not just the commerce, but also the crafts and the intellectual professions were in Jewish hands. Tailors, cobblers, carpenters, and harness-makers were 99% Jewish. The three tanneries belonged to Jews, and mills, sawmills, and alcohol breweries were rented by Jews. Like in every “Jewish Shtetl”, here were also Jewish owners of wagons, carriers and cargo-porters. The Jews had the best relations with the other inhabitants until the occupation of the Bukovina by Roumania.

As to the Jews of the Storozynetz district, their situation was the same as in the town of Storozynetz. There were no villages where Jews were not lessees of farms or of public houses. Many agricultural properties were rented and managed by Jews. The lumber trade, which was blooming in this district, was also in Jewish hands. In the rural localities the Jews also had good relationships with the other inhabitants. Entirely Roumanian or Ruthenian communities often elected Jews as their mayors, e.g. in Moldauisch-Banilla, Czudyn, Cziresch and Korczeschti. In almost all communities, Jews were the community secretaries.

The man, to whom - as above mentioned - the powerful situation of the Jews is to be credited, was Dr. Isidor Katz, who settled around 1890 as a lawyer in Storozynetz, designated at this time as a “market community”. The community-manager was the Jewish pharmacist Philipp Fuellenbaum. The locality, already inhabited by many Jews, suffered most of all from poor sanitary conditions. The Jewish apartments consisted almost everywhere of small, single-level houses of one room, or rarely of two rooms and a kitchen, where huge families lived through the day and slept at night. Although the Jewish housewife was anyway attentive to maintaining her home very clean, dust from the streets and dirt were a real obstacle to this goal. Because of that, epidemics occurred very often and the death rate in this part of Storozynetz, where the Jews lived as in a Ghetto, was quite high.

The pharmacist Fuellenbaum left for Czernowitz and Dr. Katz was then elected Mayor. After he took over the community management, he hired the medical Dr. Sussmann Kupferberg as community Medical Doctor. The latter's first assignment was to improve the sanitary conditions in common places, courtyards and especially the buildings in the Jewish sector of the locality. Roads and paths were cleaned by community employees, and particular attention was directed to sanitary objects (private and common latrines). The lighting of the streets was expanded and, to provide more security to the inhabitants, a community police force was assembled.

The whole aspect of the “market community” got, thanks to these measures, a favorable change. The managers of the different government offices located in Storozynetz fully supported the efforts of Dr. Isidor Katz. An energetic influx of Jewish merchants, craftsmen, medical doctors and lawyers, as well as government employees, among them Jews as well, increased the number of the inhabitants.

In 1898, with the occasion of the jubilee celebration of the 50 years of rule of the Emperor Franz Joseph, the market community Storozynetz was elevated to the rank of a City. Through this imperial act, the activity of Dr. Katz was fully rewarded. Thus, he began to implement his plans for the further development of the city. Under his more then 20 years of leadership, the city installed a common water supply, sewer system, and electrical lighting. Furthermore, during his mayorship, the communal slaughterhouse, the steam bath, the boy- and girl-schools, and the “Rathaus” (City Hall) were built.

Storozynetz was the residence of a district administration, a district court, a railroad district management, a revenue tax office, a district hospital, and other governmental services. Jews functioned as judges and in higher positions in other offices. The lower office staff in all services consisted of almost 80% Jews.

Before the new “Kultusgemeindegesetz” (law on Jewish communities) of 1890, the management of these communities consisted of a four-person board of directors and a 12 person Community Council. Before 1914, Dr. Isidor Katz served for decades simultaneously as the president of the “Kultusgemeinde”. To the board of directors and the Community Council belonged: Moritz Maurueber (Vice President), Berl Sternschuss, Israel Schneider, Aron (Urzi) Froelich, Maier Schneider, Motio Preminger, Berl Menczer, Jakob Locker, Adolph Lippa, Salomon Rosner, Aron Schattner, David Tuerk, Jacob Drimmer, Moses Krau and Eisig Hermann.

There were 520 taxpayers in the Community and the revenues-expenditures reached 20,000 Crowns annually. The Secretary of the Community was Moritz Brunstein.

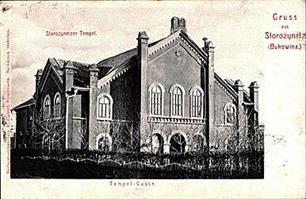

The “Kultusgemeinde” supported a Rabbi and a Dayan (Judge), for the exercise of the religious activities. Until 1914 Simcha Guensberg served as Rabbi. The construction of the big Synagogue, the Temple, was funded by volunteer donations. The Jewish rural renter Motio Weich contributed to the acquisition of the lot and also to the construction of the Temple with a significant donation.

In the Temple, services were conducted only on Friday evenings, on Saturdays and on High Holidays. For the everyday services, there were smaller prayerhouses, adjacent to the Temple: a Viznitzer, a Sadagurer and a Radautzer “Klaus” (prayerhouse). Furthermore there were a Craftsmen prayerhouse and two private prayerhouses, the property of the Rabbinical Dynasties Hager and Tabak. The last addition was the “Klaus” of the Rabbi from Czudyn, who moved to Storozynetz.

For the education of children there functioned many “Chedarim”, and for the advanced students - a “Talmud-Torah” school.

In 1871, 34 Jewish boys and 17 girls already attended the governmental public school, in 1875 - 63 boys and 39 girls, and in 1880 - 64 boys, 10% of all boys of the town and 91 girls (28.8%).

Chaim Glasner conducted the religious instruction in the public schools. There was a huge success with the founding in 1909 by Rabbi Jung (from the Hungarian village of Brod) of a Private Gymnasium with public rights, which was also attended by Christians. At this institution nearly all the teachers were Jewish.

The “Kinderheim” (orphanage) is also worthy of mention; its installation is also to the merit of Dr. Katz. The expenses of erection and maintenance of this institution were largely provided by the town savings bank, whose president was the Jewish landowner, Samuel Ohrenstein, and its executive director, Dr. Isidor Katz.

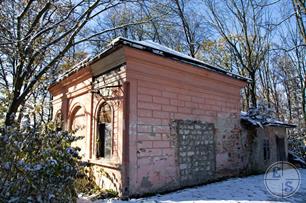

Finally, a word about the Jewish Cemetery: its maintenance and fencing was also the result of Dr. Katz's concerns. As he took over the management of the “Kultusgemeinde”, the graveyard was in a neglected situation. Many tombstones sank as a result of the weather conditions or even fell down, overgrown by grass and underbrush; the area became a pasture for beasts. A cemetery caretaker was hired, a fence built and the place got a decent appearance.

In 1904, a fire destroyed a huge part of the Jewish neighborhood.

At the beginning of the Zionist movement, a “Zionist” association was founded; its first chairman was a young lawyer-to-be Dr. Jacob Kommer. He was the one who brought to the Jews of the town the knowledge of the aims and endeavors of the movement. The lawyer DR. S. Luttinger, who managed to attract a huge part of the Jews to the “ZION” -association, succeeded him. The opposition of the most Chasidic circles didn't do much harm. Lecture-evenings had been organized, with lecturers from the Czernowitz Jewish academic associations “Hasmonaeah”, “Zephirah” and “Emunah”. Worthy of mention are: the brothers Dr. Mendel & Chaim Kinnsbrunner, Dr. Max Diamant, the brothers Dr. Marcus & Kalman Shapira, and Dr. Josef Sturm. The orator Loebl Taubes, renowned in orthodox circles, often made speeches.

Besides the “Zion”-association there functioned in Storozynetz the Jewish-Political group under Berl Sternschuss, and other associations; their assignments were exclusively for charity. The “Jewish Women's Aid Association” is worthy of mention in the first place, under the leadership of Mrs. Rosa Werth, a sister of the renowned industrialist Max Ritter (Knight) von Anhauch and of the Sanitation Councilor, Dr. David Anhauch. Almost all Jewish women from the city and surroundings were members of this association. It supported poor and sick women, providing them with medical assistance, prescription drugs, and weekly financial allocations. The association worried most of all about women at home with children and about young orphans.

Storozynetz was the residence of a district administration, a district court, a railroad district management, a revenue tax office, a district hospital, and other governmental services. Jews functioned as judges and in higher positions in other offices. The lower office staff in all services consisted of almost 80% Jews.

Before the new “Kultusgemeindegesetz” (law on Jewish communities) of 1890, the management of these communities consisted of a four-person board of directors and a 12 person Community Council. Before 1914, Dr. Isidor Katz served for decades simultaneously as the president of the “Kultusgemeinde”. To the board of directors and the Community Council belonged: Moritz Maurueber (Vice President), Berl Sternschuss, Israel Schneider, Aron (Urzi) Froelich, Maier Schneider, Motio Preminger, Berl Menczer, Jakob Locker, Adolph Lippa, Salomon Rosner, Aron Schattner, David Tuerk, Jacob Drimmer, Moses Krau and Eisig Hermann.

There were 520 taxpayers in the Community and the revenues-expenditures reached 20,000 Crowns annually. The Secretary of the Community was Moritz Brunstein.

The “Kultusgemeinde” supported a Rabbi and a Dayan (Judge), for the exercise of the religious activities. Until 1914 Simcha Guensberg served as Rabbi. The construction of the big Synagogue, the Temple, was funded by volunteer donations. The Jewish rural renter Motio Weich contributed to the acquisition of the lot and also to the construction of the Temple with a significant donation.

In the Temple, services were conducted only on Friday evenings, on Saturdays and on High Holidays. For the everyday services, there were smaller prayerhouses, adjacent to the Temple: a Viznitzer, a Sadagurer and a Radautzer “Klaus” (prayerhouse). Furthermore there were a Craftsmen prayerhouse and two private prayerhouses, the property of the Rabbinical Dynasties Hager and Tabak. The last addition was the “Klaus” of the Rabbi from Czudyn, who moved to Storozynetz.

For the education of children there functioned many “Chedarim”, and for the advanced students - a “Talmud-Torah” school.

In 1871, 34 Jewish boys and 17 girls already attended the governmental public school, in 1875 - 63 boys and 39 girls, and in 1880 - 64 boys, 10% of all boys of the town and 91 girls (28.8%).

Chaim Glasner conducted the religious instruction in the public schools. There was a huge success with the founding in 1909 by Rabbi Jung (from the Hungarian village of Brod) of a Private Gymnasium with public rights, which was also attended by Christians. At this institution nearly all the teachers were Jewish.

The “Kinderheim” (orphanage) is also worthy of mention; its installation is also to the merit of Dr. Katz. The expenses of erection and maintenance of this institution were largely provided by the town savings bank, whose president was the Jewish landowner, Samuel Ohrenstein, and its executive director, Dr. Isidor Katz.

Finally, a word about the Jewish Cemetery: its maintenance and fencing was also the result of Dr. Katz's concerns. As he took over the management of the “Kultusgemeinde”, the graveyard was in a neglected situation. Many tombstones sank as a result of the weather conditions or even fell down, overgrown by grass and underbrush; the area became a pasture for beasts. A cemetery caretaker was hired, a fence built and the place got a decent appearance.

In 1904, a fire destroyed a huge part of the Jewish neighborhood.

At the beginning of the Zionist movement, a “Zionist” association was founded; its first chairman was a young lawyer-to-be Dr. Jacob Kommer. He was the one who brought to the Jews of the town the knowledge of the aims and endeavors of the movement. The lawyer DR. S. Luttinger, who managed to attract a huge part of the Jews to the “ZION” -association, succeeded him. The opposition of the most Chasidic circles didn't do much harm. Lecture-evenings had been organized, with lecturers from the Czernowitz Jewish academic associations “Hasmonaeah”, “Zephirah” and “Emunah”. Worthy of mention are: the brothers Dr. Mendel & Chaim Kinnsbrunner, Dr. Max Diamant, the brothers Dr. Marcus & Kalman Shapira, and Dr. Josef Sturm. The orator Loebl Taubes, renowned in orthodox circles, often made speeches.

Besides the “Zion”-association there functioned in Storozynetz the Jewish-Political group under Berl Sternschuss, and other associations; their assignments were exclusively for charity. The “Jewish Women's Aid Association” is worthy of mention in the first place, under the leadership of Mrs. Rosa Werth, a sister of the renowned industrialist Max Ritter (Knight) von Anhauch and of the Sanitation Councilor, Dr. David Anhauch. Almost all Jewish women from the city and surroundings were members of this association. It supported poor and sick women, providing them with medical assistance, prescription drugs, and weekly financial allocations. The association worried most of all about women at home with children and about young orphans.

The Jewish craftsmen of all professions were united in the “Jewish Craftsmen Association”. Further, there were also a “Gemilath-Chessed” (benevolent loans without interest) association and a “Bikur-Cholim” (visiting of the sick) association; its President was Isidor Werth.

On the initiative of Dr. Katz, the Jewish Gymnasium and the Hospital were erected. Leading personalities of that period were: Shloime Drimmer, grand landowner Steiner, the medical doctors D. Seinfeld, Markus, and Joseph Menczer; the pharmacists Bruno Spielmann and Beral; the lawyers Dr. Mechel Schraenzel, Dr. Bardich, Dr. Berler, Dr. Beras, Dr. Burg, Dr. Halpern, Dr. Menczer, Schaerf, Strominger, and others; Rabbi Guensberg, born in Zadova, district Storozynetz and his son Rabbi Jacob Guensberg, a significant Rambam (Maimonides) researcher, now working in Jerusalem; Mrs. Beer, a renowned benefactress, and many others.

At the outbreak of W.W.I (1914), many well-to-do Jewish families fled to the western part of the Monarchy. Immediately after the entry of Russian troops, looting took place in the dwellings of the Jews who fled, as well as of the Jews who remained behind. A part of the local population, especially Ruthenians (Ukrainans), associated themselves with the looters and did most of the work. In the City and District many Jews were killed, and others found themselves exposed to the arbitrariness of the Russian soldiers and officers.

Although the eventual liberation of the City from Russian occupation by the Austro-Hungarian troops brought the Jewish population some relief, it had much to endure even now because of apartment requisitions.

Storozynetz was thrice occupied during the war and thrice liberated. The well-to-do Jews who survived the previous occupation, used the intermission to flee into the center of the Monarchy. Just the poor and the sick remained in the City.

In April 1918 a partial return of the Jews into the City and District Storozynetz began. Among the first to return was the mayor Dr. Isidor Katz. The Jewish “Shtetl Storozynetz” presented a desolate picture. Most of the houses were destroyed and uninhabitable, and those less damaged stood without doors and windows. The numbers of the poor and sick Jews who didn't flee from the Russians shrank to a small group. The temple was transformed into a stable and the other prayerhouses served as warehouses and depots for the Russian armies. The cemetery fence was used by a part of the population as fuel, and the Cemetery itself - as pasture for the cattle.

Not one Jewish store was to be found. The “shtetl” was unrecognizable. Despite his already feeble health, Dr. Katz began to assail the “Landesregierung” (Bukowina Provincial Government) with petitions, asking for significant help for those of the population of Storozynetz most harmed by the war. The success of these petitions and personal interventions came soon. The Landesregierung established a special office for the reconstruction of the City and District, which began its activity immediately. Although the reconstruction advanced slowly, due to shortages in materials and workmen, nevertheless the city's appearance changed visibly. Stores and shops opened their doors and a vivid trade began.

The Jewish community, numbering approximately 500 families, began the reconstruction of the Temple, the graveyard and the “Mikvah” (ritual bath). Thanks to a significant donation from the heirs of the recently deceased Jewish grand landowner Samuel Ohrenstein, the Temple and the Cemetery were soon restored. The reconstruction of the Prayerhouses and of the ritual bath was accomplished later. But, life in this community, slowly pulsating once again, suffered a new and unexpected blow with the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the annexation of Bukovina to Roumania.

On the initiative of Dr. Katz, the Jewish Gymnasium and the Hospital were erected. Leading personalities of that period were: Shloime Drimmer, grand landowner Steiner, the medical doctors D. Seinfeld, Markus, and Joseph Menczer; the pharmacists Bruno Spielmann and Beral; the lawyers Dr. Mechel Schraenzel, Dr. Bardich, Dr. Berler, Dr. Beras, Dr. Burg, Dr. Halpern, Dr. Menczer, Schaerf, Strominger, and others; Rabbi Guensberg, born in Zadova, district Storozynetz and his son Rabbi Jacob Guensberg, a significant Rambam (Maimonides) researcher, now working in Jerusalem; Mrs. Beer, a renowned benefactress, and many others.

At the outbreak of W.W.I (1914), many well-to-do Jewish families fled to the western part of the Monarchy. Immediately after the entry of Russian troops, looting took place in the dwellings of the Jews who fled, as well as of the Jews who remained behind. A part of the local population, especially Ruthenians (Ukrainans), associated themselves with the looters and did most of the work. In the City and District many Jews were killed, and others found themselves exposed to the arbitrariness of the Russian soldiers and officers.

Although the eventual liberation of the City from Russian occupation by the Austro-Hungarian troops brought the Jewish population some relief, it had much to endure even now because of apartment requisitions.

Storozynetz was thrice occupied during the war and thrice liberated. The well-to-do Jews who survived the previous occupation, used the intermission to flee into the center of the Monarchy. Just the poor and the sick remained in the City.

In April 1918 a partial return of the Jews into the City and District Storozynetz began. Among the first to return was the mayor Dr. Isidor Katz. The Jewish “Shtetl Storozynetz” presented a desolate picture. Most of the houses were destroyed and uninhabitable, and those less damaged stood without doors and windows. The numbers of the poor and sick Jews who didn't flee from the Russians shrank to a small group. The temple was transformed into a stable and the other prayerhouses served as warehouses and depots for the Russian armies. The cemetery fence was used by a part of the population as fuel, and the Cemetery itself - as pasture for the cattle.

Not one Jewish store was to be found. The “shtetl” was unrecognizable. Despite his already feeble health, Dr. Katz began to assail the “Landesregierung” (Bukowina Provincial Government) with petitions, asking for significant help for those of the population of Storozynetz most harmed by the war. The success of these petitions and personal interventions came soon. The Landesregierung established a special office for the reconstruction of the City and District, which began its activity immediately. Although the reconstruction advanced slowly, due to shortages in materials and workmen, nevertheless the city's appearance changed visibly. Stores and shops opened their doors and a vivid trade began.

The Jewish community, numbering approximately 500 families, began the reconstruction of the Temple, the graveyard and the “Mikvah” (ritual bath). Thanks to a significant donation from the heirs of the recently deceased Jewish grand landowner Samuel Ohrenstein, the Temple and the Cemetery were soon restored. The reconstruction of the Prayerhouses and of the ritual bath was accomplished later. But, life in this community, slowly pulsating once again, suffered a new and unexpected blow with the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the annexation of Bukovina to Roumania.

|

|

|

| On the road leading to Chernivtsi | ||

|

|

|

| On this street there are many nice houses | Bobik has two-story apartments |

In the short period of time between the collapse of the Monarchy and the entry of the Roumanian troops, some of the disbanded Austro-Hungarian army units went about looting Jewish apartments and stores. The Jews became again, like under the Russian occupation, powerless and helpless. Some Jewish Reserve-Officers, occasionally on leave with their families, succeeded in putting an end to the looting. Fortunately, no one was killed.

The entry of the Roumanian troops was without incident. Martial law was proclaimed, and security and defense assured to all inhabitants. The Jewish Self-Defense, organized before the entry, was disbanded, and Jews were called upon to open their stores. In some communities, where just single Jewish families lived, there were lootings.

As was said, the Jews began to attend to their professions once again, but were concerned about further developments under Roumanian rule. The measures taken by the now established local authorities in this “Yiddish Shtetl” proved that their concerns were justified. Instead of the elected mayor, who for decades had been a Jew, a Roumanian was appointed. The Community Council, where Jews also constituted the majority for decades, became almost entirely Roumanian. The Jews, Poles and Germans were granted just a few mandates.

Jewish office-holders were fired from their places and replaced by Roumanians. Everywhere the actions taken to eliminate Jewish influence were remarkable. Complaints of the Czernowitz “Jewish National Council” to the ruling authorities were ineffective, because in Czernowitz “Roumanisation” was also underway. The authority of the Jews was limited just to the management of the “Kultusgemeinde” and its institutions; moreover the manager of the “Kultusgemeinde” was now appointed by the Roumanian supervising authority.

Besides the Kultusgemeinde, the Zionist associations functioned normally. Their activities weren't limited by the authorities. Lectures were held; Chalutzim prepared for emigration to Eretz Israel; and private Hebrew schools were established. Jewish life was still active in the city.

The last elected mayor and manager of the Kultusgemeinde, Dr. Isidor Katz, former elected representative to the “Bukowiner Landtag”, followed these events only from his sickbed. He didn't live to see the decline of the “Yiddish Shtetl”. His mortal remains were buried during one of the last days of November, 1919, in an honorary grave, dedicated by the Kultusgemeinde, with almost the entire Jewish population of the City and District Storozynetz in attendance.

With the initiative of the newly appointed minister for Bukowina, Jancu von Flondor, whose grand land holdings included a significant part of the City and the District Storozynetz, and who was a deputy in the Bukowiner Landtag under Austria and was renowned as a notorious anti-Semite, the Roumanisation of the city began at a speedy pace. Roumanian stores, shops and workshops appeared over night.

The Jewish merchants and craftsmen saw themselves engaged in a competition in which they were at a distinct disadvantage. While the Jews were obliged to pay high income taxes, The Roumanians got tax-discounts and even tax-exemptions.

The Authorities found volunteer Roumanisation assistants among the Roumanian clergy and teachers. In sermons and speeches, the Roumanians and other Christians were implored not to buy from Jews and to boycott their stores. The apogee of the boycott was reached under the government of Goga-Cuza (10.37-02.38), when the Roumanian peasantry feared entry into a Jewish store. Often the boycott was followed by excesses against the Jewish population. The boycott was successful: instead of the once well-to-do Jews, we now had a needy and poor community.

This was the picture of the “Yiddish Shtetl” Storozynetz around the year 1940.

The entry of the Roumanian troops was without incident. Martial law was proclaimed, and security and defense assured to all inhabitants. The Jewish Self-Defense, organized before the entry, was disbanded, and Jews were called upon to open their stores. In some communities, where just single Jewish families lived, there were lootings.

As was said, the Jews began to attend to their professions once again, but were concerned about further developments under Roumanian rule. The measures taken by the now established local authorities in this “Yiddish Shtetl” proved that their concerns were justified. Instead of the elected mayor, who for decades had been a Jew, a Roumanian was appointed. The Community Council, where Jews also constituted the majority for decades, became almost entirely Roumanian. The Jews, Poles and Germans were granted just a few mandates.

Jewish office-holders were fired from their places and replaced by Roumanians. Everywhere the actions taken to eliminate Jewish influence were remarkable. Complaints of the Czernowitz “Jewish National Council” to the ruling authorities were ineffective, because in Czernowitz “Roumanisation” was also underway. The authority of the Jews was limited just to the management of the “Kultusgemeinde” and its institutions; moreover the manager of the “Kultusgemeinde” was now appointed by the Roumanian supervising authority.

Besides the Kultusgemeinde, the Zionist associations functioned normally. Their activities weren't limited by the authorities. Lectures were held; Chalutzim prepared for emigration to Eretz Israel; and private Hebrew schools were established. Jewish life was still active in the city.

The last elected mayor and manager of the Kultusgemeinde, Dr. Isidor Katz, former elected representative to the “Bukowiner Landtag”, followed these events only from his sickbed. He didn't live to see the decline of the “Yiddish Shtetl”. His mortal remains were buried during one of the last days of November, 1919, in an honorary grave, dedicated by the Kultusgemeinde, with almost the entire Jewish population of the City and District Storozynetz in attendance.

With the initiative of the newly appointed minister for Bukowina, Jancu von Flondor, whose grand land holdings included a significant part of the City and the District Storozynetz, and who was a deputy in the Bukowiner Landtag under Austria and was renowned as a notorious anti-Semite, the Roumanisation of the city began at a speedy pace. Roumanian stores, shops and workshops appeared over night.

The Jewish merchants and craftsmen saw themselves engaged in a competition in which they were at a distinct disadvantage. While the Jews were obliged to pay high income taxes, The Roumanians got tax-discounts and even tax-exemptions.

The Authorities found volunteer Roumanisation assistants among the Roumanian clergy and teachers. In sermons and speeches, the Roumanians and other Christians were implored not to buy from Jews and to boycott their stores. The apogee of the boycott was reached under the government of Goga-Cuza (10.37-02.38), when the Roumanian peasantry feared entry into a Jewish store. Often the boycott was followed by excesses against the Jewish population. The boycott was successful: instead of the once well-to-do Jews, we now had a needy and poor community.

This was the picture of the “Yiddish Shtetl” Storozynetz around the year 1940.

|

|

|

| Jewish cemetery, 2016 | Beit Kadishim - Farewell House | |

|

|

|

| Common grave | ||

|

|

|

| The family crypt of Orenshtayn | ||

|

|

|

| Mayor of the city Isidor Katz |

The occupation of the city by the Soviet Army in May, 1940, brought new “Tzurec” (sorrows) to the Jews. The laws of the Soviet Union were introduced immediately following the occupation. Whereas private commerce was prohibited there, so it was prohibited in the new province as well. All the private stores were closed and the merchandise confiscated (“nationalized”). This measure harmed exclusively the Jewish merchants, because the Roumanian storeowners fled from the Soviets together with the retreating Roumanian Army, taking their stocks along with them.

Overnight, the Jewish merchants became beggars. After the confiscation of the warestocks began the registration of the population, which caused new sufferings to the Jews, especially to the Jewish merchants. A great number of them were declared “exploiters” and “parasites” and deported to Siberia on 13 June 1941. The same destiny came to Jews who were known to be Zionists, Revisionists or Bundists, most of them denounced by Jewish Communists.

The few who remained, among them intellectuals, too, were compelled to earn their keep through unskilled labor. Whereas the “Kultusgemeinde” was prohibited, there was no organization to worry about the religious needs of the Jewish population. The temple was closed, and services were held secretly in one of the small prayerhouses. All Jewish activities ceased to function.

This was the situation of the few Jews, who remained in the city, when the Russians, after one year of occupation, left Storozynetz in July, 1941, as a consequence of Hitler's Germany declaring war on the Soviet-Union. The entry of the German-Roumanian armies sealed the destiny of the City's and District's Jews. On their advance, the troops reached the locality Czudyn, not far from Storozynetz, and shot almost all the Jewish inhabitants, whose number amounted to approximately 600. Just 4 Jews managed to escape.

The same destiny reached the Jews from Mold. Banila and Zadowa, two rural communities belonging to the district Storozynetz. Whereas the Storozynetz District numbered more than 40 rural communities, and in each community lived several Jewish families, it was impossible to determine the number of casualties in each locality. It is nevertheless certain that no community inhabited by Jews was spared. Whoever could escape through bribery or by chance, ended up later in the death camps of Transnistria.

Plenty of dead victims were mourned in the city, among them the last leaders of the Kultusgemeinde, appointed by the Roumanian Authorities, Salomon Drimmer and Simon Schaefler. If somebody was met during the advance of the troops and recognized as a Jew, he was shot on the spot. Given that the Jews didn't leave their apartments because of fear, the corpses were left just where they were shot. Only after the intervention of the otherwise not too Jew-friendly land owner Sherban Flondor - a son of the above mentioned former minister for Bukowina, Jancu Flondor - were the corpses gathered by the communal catafalque and buried in a common grave at the Jewish graveyard. At this burial, Jews were prohibited from taking part.

All other Jews who remained alive, with exception of three medical doctors, Dr. Seinfeld, Dr. Klinghofer and Dr. Rauchwerger, as well as the pharmacist Stappler, the tinsmith Boruch, and a specialist in alcohol distillation Steiner, later killed by Russian gangs, were compelled to go to Transnistria; some by foot, some in vehicles, but always under the vigilant eye of soldiers and gendarmes, armed with batons and whips. They left their houses, furniture, clothing and wash to their murderers. The City and District Storozynetz were now almost “Judenrein” (without any Jews). On their way to the death camps of Transnistria, they passed the road from which a path led to the Jewish Cemetery. It is there that they directed their gaze and took leave of the dead and Kedoshim (martyrs) who rested there.

Only a few survived the stay in the Transnistrian camps, the others who perished there decayed in the Ukrainian steppes.

Shortly before his departure from the Soviet Union in April, 1945, the writer of these lines went back to his hometown Storozynetz to visit the graves of his parents, grandparents and relatives, who rest there in the Jewish Cemetery. The graveyard presented a terrible picture. Most tombstones were destroyed or overthrown by missiles. The city itself was unrecognizable, it looked like a pile of rubble. Most of the houses were destroyed and uninhabited. Just ten Jewish families still lived there; Jews who survived the hell in Storozynetz or in the Transnistria death camps. These families were soon to find their way to Israel, the eternal homeland of the Jewish people.

Overnight, the Jewish merchants became beggars. After the confiscation of the warestocks began the registration of the population, which caused new sufferings to the Jews, especially to the Jewish merchants. A great number of them were declared “exploiters” and “parasites” and deported to Siberia on 13 June 1941. The same destiny came to Jews who were known to be Zionists, Revisionists or Bundists, most of them denounced by Jewish Communists.

The few who remained, among them intellectuals, too, were compelled to earn their keep through unskilled labor. Whereas the “Kultusgemeinde” was prohibited, there was no organization to worry about the religious needs of the Jewish population. The temple was closed, and services were held secretly in one of the small prayerhouses. All Jewish activities ceased to function.

This was the situation of the few Jews, who remained in the city, when the Russians, after one year of occupation, left Storozynetz in July, 1941, as a consequence of Hitler's Germany declaring war on the Soviet-Union. The entry of the German-Roumanian armies sealed the destiny of the City's and District's Jews. On their advance, the troops reached the locality Czudyn, not far from Storozynetz, and shot almost all the Jewish inhabitants, whose number amounted to approximately 600. Just 4 Jews managed to escape.

The same destiny reached the Jews from Mold. Banila and Zadowa, two rural communities belonging to the district Storozynetz. Whereas the Storozynetz District numbered more than 40 rural communities, and in each community lived several Jewish families, it was impossible to determine the number of casualties in each locality. It is nevertheless certain that no community inhabited by Jews was spared. Whoever could escape through bribery or by chance, ended up later in the death camps of Transnistria.

Plenty of dead victims were mourned in the city, among them the last leaders of the Kultusgemeinde, appointed by the Roumanian Authorities, Salomon Drimmer and Simon Schaefler. If somebody was met during the advance of the troops and recognized as a Jew, he was shot on the spot. Given that the Jews didn't leave their apartments because of fear, the corpses were left just where they were shot. Only after the intervention of the otherwise not too Jew-friendly land owner Sherban Flondor - a son of the above mentioned former minister for Bukowina, Jancu Flondor - were the corpses gathered by the communal catafalque and buried in a common grave at the Jewish graveyard. At this burial, Jews were prohibited from taking part.

All other Jews who remained alive, with exception of three medical doctors, Dr. Seinfeld, Dr. Klinghofer and Dr. Rauchwerger, as well as the pharmacist Stappler, the tinsmith Boruch, and a specialist in alcohol distillation Steiner, later killed by Russian gangs, were compelled to go to Transnistria; some by foot, some in vehicles, but always under the vigilant eye of soldiers and gendarmes, armed with batons and whips. They left their houses, furniture, clothing and wash to their murderers. The City and District Storozynetz were now almost “Judenrein” (without any Jews). On their way to the death camps of Transnistria, they passed the road from which a path led to the Jewish Cemetery. It is there that they directed their gaze and took leave of the dead and Kedoshim (martyrs) who rested there.

Only a few survived the stay in the Transnistrian camps, the others who perished there decayed in the Ukrainian steppes.

Shortly before his departure from the Soviet Union in April, 1945, the writer of these lines went back to his hometown Storozynetz to visit the graves of his parents, grandparents and relatives, who rest there in the Jewish Cemetery. The graveyard presented a terrible picture. Most tombstones were destroyed or overthrown by missiles. The city itself was unrecognizable, it looked like a pile of rubble. Most of the houses were destroyed and uninhabited. Just ten Jewish families still lived there; Jews who survived the hell in Storozynetz or in the Transnistria death camps. These families were soon to find their way to Israel, the eternal homeland of the Jewish people.

Sources:

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia

- Adolphe Rosenwald. Storozhinets / Geschichte der Juden in der Bukowina (History of the Jews in the Bukowina), vol. II. Edited by Hugo Gold. Tel Aviv: Olamenu, 1962. Translated from German by Isak Shteyn, JewishGen, Inc

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

- Postcard collection of Eduard Turkevych

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia

- Adolphe Rosenwald. Storozhinets / Geschichte der Juden in der Bukowina (History of the Jews in the Bukowina), vol. II. Edited by Hugo Gold. Tel Aviv: Olamenu, 1962. Translated from German by Isak Shteyn, JewishGen, Inc

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

- Postcard collection of Eduard Turkevych

Chernivtsi region - list of settlements and location of objects

Storozhynets, 2014, 2016

Storozhynets, 2014, 2016

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine