Novoselytsia

The oldest written mention of Novoselytsia dates back to 1456.

Until 1918, Novoselitsya had a triple junction of the borders of the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Rumunia.

Until 2020 the city of Novoselytsia was district center in Chernivtsi region.

In 1800, 99 Jews (10.7%) lived in Novoselytsia,

in 1847 - 81 Jewish family,

in 1850 - approx. 250 Jews (10.8%),

in 1897 - 3898 (66.2%),

in 1930 - 4154 Jews (86.1%).

Until 1918, Novoselitsya had a triple junction of the borders of the Russian Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Rumunia.

Until 2020 the city of Novoselytsia was district center in Chernivtsi region.

In 1800, 99 Jews (10.7%) lived in Novoselytsia,

in 1847 - 81 Jewish family,

in 1850 - approx. 250 Jews (10.8%),

in 1897 - 3898 (66.2%),

in 1930 - 4154 Jews (86.1%).

|

|

|

|

| Post office | Hotel | Bank | |

|

|

|

|

| Modern street with preserved old houses | |||

|

|

|

|

| A few old villas that are no longer there |

Chernivtsi district, Chernivtsi region

|

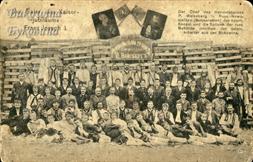

| Joint Russian-Austrian celebration of the birthday of Emperor Franz Josef, 1908. And advertising of Pinhas Weisberg in the center |

|

|

|

|

| Great synagogue in Novoselytsia, 2016 | Synagogue frescoes were discovered under layers of plaster | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lenin - a classic biblical story) In Soviet times there was a club here | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The settlement of Novoselitsa began in the 18th century during the Turkish rule of Moldova. The town served as a transit station for cattle and sheep herds. The Jewish community was centered mainly in the western section of town near the Austrian border. The border had been established after Bucovina was annexed in 1774. This area was named Contra Mass and the Russians, after the annexation of Bessarabia in 1812, called it Novoselitsa (new settlement). The Jewish community institutions were also located there: the old house of study, Hekdesh and the bathhouse. The deceased were brought to burial in the Jewish cemetery of Clishkauts, about 20 km away.

During the rule of the Moldovan prince Struza (1790-1820), i.e. before annexation by Russia, the Jewish community developed. The estate owner invited Jews from across the border, from Ukraine, Poland and Bucovina, to settle there. The Jews were given certain privileges according to the accepted practice towards all settlers in Bessarabia at the time. The new community in Novoselitsa centered near the cattle market. The two communities, the old and the new, were separated by a large marsh. There was also a spiritual separation between the two groups and they only united for self defence against attacks.

There was a local legend among the Jews. They were discriminated against by the non-Jews, especially by the Church that stood on the road leading to the “Small Prut River”. One day, the funeral procession of the local Rabbi passed there and the non-Jews watching began to throw stones. A commotion ensued and suddenly the deceased woke up, the funeral procession stopped…the deceased who arose recited a few biblical verses…the church fell, sank in the ground and disappeared…the Christians erected a memorial chapel in that place. The Jews referred to it as the “Small cursed church”.

During the Russian conquest (1812-1918) the border between Russia and Austria went through the town and divided it into two sections. One was the Russian-Bessarabian and the other the Bucovina-Austrian. The town became a transit point for people and merchandise from Russia to central Europe. All agricultural products from northern and central Bessarabia intended for export had to pass through Novoselitsa. Commerce was thriving and the economic situation was improving. All import and export was in the hands of Jews and the community was growing. The marshland became an area of new homes, stores and warehouses.

The Jewish population did well. The town developed due to their success and became a well-known commercial center. The lumber yards were located on the banks of the Prut River. The logs had been brought there on rafts from Austria. A local Jew called Pinhas Weisberg, originally from Ukraine, established a sawmill and employed hundreds of laborers and clerks. He also built a suburb named after him. It had a tiny theater where there were performances in Yiddish and in Russian. (During the Russian revolution the theater was burned and Weisberg was arrested and deported to Siberia).

In 1870, a distillery, a steam mill, two tanneries owned by Moishe Adelman and Ancel Goldenberg, the creamery of merchant Mordko Kleitman, the soap factory of Sura Shapiro, worked in the town.

The Jews of Novoselitsa in Bessarabia and their neighbors on the Bucovina side were on good terms. Although there was a border between them they had strong economic ties. There was much contraband and those involved controlled the police and border guards. During the large immigration from Russia to America Novoselitsa served as an organized transit station for illegal immigrants. The famous “Pekl machers” (organizers) brought immigrants from all over Russia there, and they helped thousands of Jews to cross the Russia-Austria border on their way to America. Even many of the local young people were drawn to this movement and immigrated to South American countries.

During the rule of the Moldovan prince Struza (1790-1820), i.e. before annexation by Russia, the Jewish community developed. The estate owner invited Jews from across the border, from Ukraine, Poland and Bucovina, to settle there. The Jews were given certain privileges according to the accepted practice towards all settlers in Bessarabia at the time. The new community in Novoselitsa centered near the cattle market. The two communities, the old and the new, were separated by a large marsh. There was also a spiritual separation between the two groups and they only united for self defence against attacks.

There was a local legend among the Jews. They were discriminated against by the non-Jews, especially by the Church that stood on the road leading to the “Small Prut River”. One day, the funeral procession of the local Rabbi passed there and the non-Jews watching began to throw stones. A commotion ensued and suddenly the deceased woke up, the funeral procession stopped…the deceased who arose recited a few biblical verses…the church fell, sank in the ground and disappeared…the Christians erected a memorial chapel in that place. The Jews referred to it as the “Small cursed church”.

During the Russian conquest (1812-1918) the border between Russia and Austria went through the town and divided it into two sections. One was the Russian-Bessarabian and the other the Bucovina-Austrian. The town became a transit point for people and merchandise from Russia to central Europe. All agricultural products from northern and central Bessarabia intended for export had to pass through Novoselitsa. Commerce was thriving and the economic situation was improving. All import and export was in the hands of Jews and the community was growing. The marshland became an area of new homes, stores and warehouses.

The Jewish population did well. The town developed due to their success and became a well-known commercial center. The lumber yards were located on the banks of the Prut River. The logs had been brought there on rafts from Austria. A local Jew called Pinhas Weisberg, originally from Ukraine, established a sawmill and employed hundreds of laborers and clerks. He also built a suburb named after him. It had a tiny theater where there were performances in Yiddish and in Russian. (During the Russian revolution the theater was burned and Weisberg was arrested and deported to Siberia).

In 1870, a distillery, a steam mill, two tanneries owned by Moishe Adelman and Ancel Goldenberg, the creamery of merchant Mordko Kleitman, the soap factory of Sura Shapiro, worked in the town.

The Jews of Novoselitsa in Bessarabia and their neighbors on the Bucovina side were on good terms. Although there was a border between them they had strong economic ties. There was much contraband and those involved controlled the police and border guards. During the large immigration from Russia to America Novoselitsa served as an organized transit station for illegal immigrants. The famous “Pekl machers” (organizers) brought immigrants from all over Russia there, and they helped thousands of Jews to cross the Russia-Austria border on their way to America. Even many of the local young people were drawn to this movement and immigrated to South American countries.

The exact dates of the establishment of the community in Novoselitsa are unknown. For many generations the administration of the community was in the hands of a powerful veteran family, that of Moshe Kahalsman and his heirs. They were the collectors of the Meat Tax and became rich on public funds. The institutions in the community were the Talmud Torah, Hekdesh school, Mikve, Hevra Kaddisha (1841) and the Fund for the Poor. The rabbis and ritual slaughterers in Novoselitsa were elected and were members of the righteous of Rozhin. They were in charge in town.

The Hassidim of Novoselitsa were from the Sadigura sect across the border. They ruled on all matters in the community. The Tax collectors used this fact and took a majority of the collection for their own benefit. The clergy and those serving the community lived in dire poverty.

The Sadigura Hassidim invited the outstanding Rabbi Faso from Zvul to come to town. He was a brilliant scholar and always fielded questions and answers from other Torah scholars. After his death he was succeeded by his son-in-law, Rabbi Haim Hier, a Boyan Hassid. Together with members of his family he established a plant to incinerate bricks and factories for the manufacturing of soap and noodles. They sold their products in town and nearby. His son-in-law, a learned young rabbi from Radomisel, Ukraine, succeeded him. He then became involved with the Zionist movement. On Shabbat he used to speak in synagogue in Hebrew and always in a Zionist spirit. His articles appeared in Hatzfira. He also served as the first principal of the Hebrew day school in Novoselitsa. He also took part in the Zionist Congress in Vienna and was also a representative in the Tarbut committee.

The ritual slaughterer and inspector, Nahum Schechter, was highly involved in the Talmud Torah and he looked after the poor in town in general and their children in particular. Every child who wore a small talit was awarded a kopeck by him. Due to his influence, the bachelor Rabbi Krakushansky was able to tutor some young men in the old house of study and thus earn a simple living.

The old synagogue was built in the days of Prince Struza in 1780. It was nicknamed the “Turkish synagogue” because it had been established during the Turkish rule of Moldova.

The Great synagogue was founded in 1854. It was populated by many craftsmen: wagon drivers, porters, laborers and was also the headquarters for the Hevra Kaddisha. Many Zionist assemblies were held there.

The Synagogue of the Boyan Hassidim was built in the 1890s. The local followers named the synagogue after Rabbi Yitzhak Frides, a leader from Boyan, to commemorate the fact that he moved to Novoselitsa. The Sadigura followers also erected a synagogue at the time that Rabbi Israel from Rozin fled from Russia and settled in Sadigura. The synagogue became a center for Hassidim in Novoselitsa.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were 10 synagogues in Novoselitsa.

The Hassidim of Novoselitsa were from the Sadigura sect across the border. They ruled on all matters in the community. The Tax collectors used this fact and took a majority of the collection for their own benefit. The clergy and those serving the community lived in dire poverty.

The Sadigura Hassidim invited the outstanding Rabbi Faso from Zvul to come to town. He was a brilliant scholar and always fielded questions and answers from other Torah scholars. After his death he was succeeded by his son-in-law, Rabbi Haim Hier, a Boyan Hassid. Together with members of his family he established a plant to incinerate bricks and factories for the manufacturing of soap and noodles. They sold their products in town and nearby. His son-in-law, a learned young rabbi from Radomisel, Ukraine, succeeded him. He then became involved with the Zionist movement. On Shabbat he used to speak in synagogue in Hebrew and always in a Zionist spirit. His articles appeared in Hatzfira. He also served as the first principal of the Hebrew day school in Novoselitsa. He also took part in the Zionist Congress in Vienna and was also a representative in the Tarbut committee.

The ritual slaughterer and inspector, Nahum Schechter, was highly involved in the Talmud Torah and he looked after the poor in town in general and their children in particular. Every child who wore a small talit was awarded a kopeck by him. Due to his influence, the bachelor Rabbi Krakushansky was able to tutor some young men in the old house of study and thus earn a simple living.

The old synagogue was built in the days of Prince Struza in 1780. It was nicknamed the “Turkish synagogue” because it had been established during the Turkish rule of Moldova.

The Great synagogue was founded in 1854. It was populated by many craftsmen: wagon drivers, porters, laborers and was also the headquarters for the Hevra Kaddisha. Many Zionist assemblies were held there.

The Synagogue of the Boyan Hassidim was built in the 1890s. The local followers named the synagogue after Rabbi Yitzhak Frides, a leader from Boyan, to commemorate the fact that he moved to Novoselitsa. The Sadigura followers also erected a synagogue at the time that Rabbi Israel from Rozin fled from Russia and settled in Sadigura. The synagogue became a center for Hassidim in Novoselitsa.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were 10 synagogues in Novoselitsa.

When WWI broke out there were battles on the border. After a few days the Austrians conquered the villages and hamlets and remained in Novoselitsa for a month. The Russians attacked and entered the area belonging to the Austrians. It seemed as if life returned to normal, but all the institutions were closed. The commander of the Russian headquarters, Great Prince Nikolai Nikolayevich, ordered the expulsion of all Jewish residents from the area. Thousands of Jews were sent without any belongings to distant places in Russia.

The Russian General Klar, a native of Kurland in Germany, supervised the expulsion of the Jews of Novoselitsa, but another Russian officer, a colonel born in Siberia, tried to defend them. He maintained that there were no spies or traitors among the Jews and he even approached the central headquarters to cancel the order. Only a few families were sent to Siberia after being denounced and some of them died there.

As the frontier became closer to town many of the Jews of Novoselitsa escaped to distant villages such as Lipcani and Secureni. The people of Secureni received the refugees as members of their family and found lodgings for them. Studies were never interrupted in the Hebrew day school, the Talmud Torah and various Heders in Novoselitsa. The Jews also continued to pray in synagogues although they were forbidden from speaking Yiddish or Hebrew. Many Jews from Novoselitsa were drafted into the army and many excelled during their military service.

Education in Novoselitsa was quite traditional: Heder, Talmud Torah, but no government schools. The spirit of enlightenment reached here, too. Private tutors taught Hebrew and general studies in Hebrew and Russian helped to advance Hebrew culture. In the years before WWI a library was established, first in secret, with hundreds of volumes in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian. Hundreds of readers frequented the library.

A group of young people was formed around it and they held reading sessions as well as Zionist activities. The library was closed during the war by the authorities and the books were removed. Evening courses in Hebrew were held secretly. The first “Repaired Heder” opened at the beginning of the 20th century did not succeed. Instead, the Zionist established a modern school where Hebrew subjects were taught in Hebrew.

The Russian General Klar, a native of Kurland in Germany, supervised the expulsion of the Jews of Novoselitsa, but another Russian officer, a colonel born in Siberia, tried to defend them. He maintained that there were no spies or traitors among the Jews and he even approached the central headquarters to cancel the order. Only a few families were sent to Siberia after being denounced and some of them died there.

As the frontier became closer to town many of the Jews of Novoselitsa escaped to distant villages such as Lipcani and Secureni. The people of Secureni received the refugees as members of their family and found lodgings for them. Studies were never interrupted in the Hebrew day school, the Talmud Torah and various Heders in Novoselitsa. The Jews also continued to pray in synagogues although they were forbidden from speaking Yiddish or Hebrew. Many Jews from Novoselitsa were drafted into the army and many excelled during their military service.

Education in Novoselitsa was quite traditional: Heder, Talmud Torah, but no government schools. The spirit of enlightenment reached here, too. Private tutors taught Hebrew and general studies in Hebrew and Russian helped to advance Hebrew culture. In the years before WWI a library was established, first in secret, with hundreds of volumes in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian. Hundreds of readers frequented the library.

A group of young people was formed around it and they held reading sessions as well as Zionist activities. The library was closed during the war by the authorities and the books were removed. Evening courses in Hebrew were held secretly. The first “Repaired Heder” opened at the beginning of the 20th century did not succeed. Instead, the Zionist established a modern school where Hebrew subjects were taught in Hebrew.

The first Zionists in Novoselitsa were members of Lovers of Zion and “Language of the Past”. Until 1914 Zionist activity in Russia was almost all done in secret in fear of the Tsarist authorities. One of the Zionist leaders in Novoselitsa was Yehiel Schwartz who was very active in instilling the Zionist spirit in the younger generation. (His son-in-law is the former Minister of Defence Moshe Dayan and another son-in-law is the former Commander of the Air Force Ezer Weitzman).

The Zamir choir was founded in Novoselitsa before the revolution. It sang popular Hebrew and Yiddish songs. After the revolution the Zionist movement affected the whole community. The library was reopened and over 1000 volumes were added to those returned by the authorities. In 1917, the first Zionist assembly was held in the Boyan Synagogue. It was attended by over 500 young men and women and produced a new branch called “Shield of Avraham”.

A municipal committee was elected consisting of Zionists and ultra-Orthodox members. The Hebrew school was reopened and evening courses in Hebrew and Yiddish were offered. All of this was free. Every Shabbat public lectures were given. A national Zionist club was founded and Jewish organizations participated in celebrations on May 1, 1917. The Zionist organizations made certain that the Hebrew flag hung next to the Red one.

When the wave of anti-Semitic attacks hit the town and pogroms occurred in Kishinev and Kalarash (1903-1905), there was a fear of similar events in Novoselitsa. Many Jewish soldiers deserted from the Russian army during the war with Japan and many of them reached Novoselitsa in order to smuggle across the border and go to America. Many refugees of the riots also came to town with the same purpose in mind. The Russian General who commanded the brigade guarding the border promised to look after the Jews. He kept his promise. He sent horsemen on a daily basis to protect the roads to Novoselitsa from rioters and hooligans. The soldiers even shot at them.

The Jews of Novoselitsa even organized, for the first time, a self-defence group. It was comprised of people from all walks of life. They stood on guard armed with guns that had been smuggled across the border. The Jews of the Austrian Novoselitsa organized an army unit hoping to activate it in an emergency in the Russian Novoselitsa. The local Russian authorities discovered this fact and they did not want interference from the outside. They local authorities did not really allow it either, but the Jews of Novoselitsa were prepared against the threat of the rioters.

That year Bessarabia and Novoselitsa saw the arrival of many young people from Romania who had deserted from the army. A few hundred of them stopped in Novoselitsa and were received warmly by the local Jews. A group of women founded “Social Assistance” and they looked after these refugees as well. The community council managed to obtain permission for the refugees to remain in town even though they had been ordered to leave.

When the Russian frontier fell after the revolution thousands of deserters appeared and threatened the community with murders and thefts. A “Self-Defence” group was organized. There were 300 men who were all well equipped and armed. This self defence group established order and discipline in town. The store owners were not allowed to gouge prices and there was supervision of liquor. Guards in town were located in different areas and there was constant communication with the defence headquarters. When there was news of rioters in a nearby village, 50 brave young men volunteered to go there to teach the hooligans a lesson. They were well-armed and disciplined. The hooligans ran away and their groups were dispersed.

The local farmers suffered from these hooligans and they asked the local Jewish defence group to help them. In the winter 0f 1918-1919 the Austrian army reached northern Bessarabia and the arms and equipment of the self defence group were hidden.

On the eve of WWI Novoselitsa reached the heights of economic development. What began as a tiny, unknown settlement became a well-established thriving community of 10 000 inhabitants. Most of the residents earned their living by commerce and many were craftsmen: tailors, carpenters, shoemakers, fur and leather hat makers, butchers, tinsmiths, locksmiths, blacksmiths, porters, wagon drivers, laborers and clerks in shops packing and selling eggs, lumber, tiles as well as agents and clerks in cattle and other export and import businesses. There were also smugglers who brought people and goods across the border.

Jews owned the only pharmacy, both pharmacy warehouses, bakery, a photo studio, 110 stores (including all 33 bacalemes, all 26 tobacco, all 9 winery).

In 1912, a Jewish loan-saving society acted.

When the Austrian army entered northern Bessarabia in spring 1918 life went back to normal. The Austrians (among them were many Jewish soldiers and officers and even Zionists) behaved well towards the Jews and allowed them to re-establish their institutions.

The economic situation improved after so many years of suffering during the war and the revolution. Farmers from nearby villages in Bucovina came to Novoselitsa to sell their produce and to buy what they needed. Again Novoselitsa became an important commercial center which connected east and west.

The municipal committee formed during the revolution saw a rebirth in a new framework according to the needs of the times and the authorities. Permits were issued for import and export and there was no tax on commerce. Life was good for Jews under the Austrian regime. Jews from nearby Austria, as well as army personnel, became closer with the Jews of Novoselitsa.

There was a Jewish Austrian officer, Dr. Landau from Krakow, who was educated and lectured in the Zionist club on Jewish topics. At Passover 1918 there was a Seder for all Jewish officers and soldiers in the Austrian army. The youth were dedicated to this activity and the residents of the town donated towards the expenses involved.

The Zamir choir was founded in Novoselitsa before the revolution. It sang popular Hebrew and Yiddish songs. After the revolution the Zionist movement affected the whole community. The library was reopened and over 1000 volumes were added to those returned by the authorities. In 1917, the first Zionist assembly was held in the Boyan Synagogue. It was attended by over 500 young men and women and produced a new branch called “Shield of Avraham”.

A municipal committee was elected consisting of Zionists and ultra-Orthodox members. The Hebrew school was reopened and evening courses in Hebrew and Yiddish were offered. All of this was free. Every Shabbat public lectures were given. A national Zionist club was founded and Jewish organizations participated in celebrations on May 1, 1917. The Zionist organizations made certain that the Hebrew flag hung next to the Red one.

When the wave of anti-Semitic attacks hit the town and pogroms occurred in Kishinev and Kalarash (1903-1905), there was a fear of similar events in Novoselitsa. Many Jewish soldiers deserted from the Russian army during the war with Japan and many of them reached Novoselitsa in order to smuggle across the border and go to America. Many refugees of the riots also came to town with the same purpose in mind. The Russian General who commanded the brigade guarding the border promised to look after the Jews. He kept his promise. He sent horsemen on a daily basis to protect the roads to Novoselitsa from rioters and hooligans. The soldiers even shot at them.

The Jews of Novoselitsa even organized, for the first time, a self-defence group. It was comprised of people from all walks of life. They stood on guard armed with guns that had been smuggled across the border. The Jews of the Austrian Novoselitsa organized an army unit hoping to activate it in an emergency in the Russian Novoselitsa. The local Russian authorities discovered this fact and they did not want interference from the outside. They local authorities did not really allow it either, but the Jews of Novoselitsa were prepared against the threat of the rioters.

That year Bessarabia and Novoselitsa saw the arrival of many young people from Romania who had deserted from the army. A few hundred of them stopped in Novoselitsa and were received warmly by the local Jews. A group of women founded “Social Assistance” and they looked after these refugees as well. The community council managed to obtain permission for the refugees to remain in town even though they had been ordered to leave.

When the Russian frontier fell after the revolution thousands of deserters appeared and threatened the community with murders and thefts. A “Self-Defence” group was organized. There were 300 men who were all well equipped and armed. This self defence group established order and discipline in town. The store owners were not allowed to gouge prices and there was supervision of liquor. Guards in town were located in different areas and there was constant communication with the defence headquarters. When there was news of rioters in a nearby village, 50 brave young men volunteered to go there to teach the hooligans a lesson. They were well-armed and disciplined. The hooligans ran away and their groups were dispersed.

The local farmers suffered from these hooligans and they asked the local Jewish defence group to help them. In the winter 0f 1918-1919 the Austrian army reached northern Bessarabia and the arms and equipment of the self defence group were hidden.

On the eve of WWI Novoselitsa reached the heights of economic development. What began as a tiny, unknown settlement became a well-established thriving community of 10 000 inhabitants. Most of the residents earned their living by commerce and many were craftsmen: tailors, carpenters, shoemakers, fur and leather hat makers, butchers, tinsmiths, locksmiths, blacksmiths, porters, wagon drivers, laborers and clerks in shops packing and selling eggs, lumber, tiles as well as agents and clerks in cattle and other export and import businesses. There were also smugglers who brought people and goods across the border.

Jews owned the only pharmacy, both pharmacy warehouses, bakery, a photo studio, 110 stores (including all 33 bacalemes, all 26 tobacco, all 9 winery).

In 1912, a Jewish loan-saving society acted.

When the Austrian army entered northern Bessarabia in spring 1918 life went back to normal. The Austrians (among them were many Jewish soldiers and officers and even Zionists) behaved well towards the Jews and allowed them to re-establish their institutions.

The economic situation improved after so many years of suffering during the war and the revolution. Farmers from nearby villages in Bucovina came to Novoselitsa to sell their produce and to buy what they needed. Again Novoselitsa became an important commercial center which connected east and west.

The municipal committee formed during the revolution saw a rebirth in a new framework according to the needs of the times and the authorities. Permits were issued for import and export and there was no tax on commerce. Life was good for Jews under the Austrian regime. Jews from nearby Austria, as well as army personnel, became closer with the Jews of Novoselitsa.

There was a Jewish Austrian officer, Dr. Landau from Krakow, who was educated and lectured in the Zionist club on Jewish topics. At Passover 1918 there was a Seder for all Jewish officers and soldiers in the Austrian army. The youth were dedicated to this activity and the residents of the town donated towards the expenses involved.

|

|

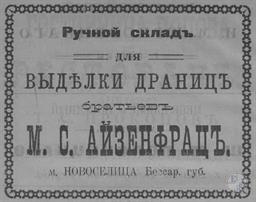

| Advertising of Pinhas Weisberg in Novoselitsa, 1912 | Advertising of Jewish merchants Aizenfrants brothers in Novoselitsa, 1912 |

The first Romanian commander in town was a Jewish officer. He was kind to the Jewish population and gave permits to the merchants to import food and other goods. Between the two regimes economic life was slow and many residents did not earn anything. The craftsmen were in a better position than the merchants because the Jewish Federation gave them loans at a low interest.

During the Romanian rule the situation worsened and the middle class could not even get loans. The years of drought and heavy taxes were harder on the Jews than on their Christian neighbors who were given more privileges. The situation was so dire that there was mass immigration to South America, Peru, Venezuela, Panama and Ecuador. After many years of hard work of preparation the youth managed to make Aliyah.

Between the two wars there were different institutions that were formed in Novoselitsa: Business and Loan Bank that gave loans to merchants at a low rate of interest, Savings and Loan Bank for small commerce, etc.

In the summer of 1918 there was an area conference of Zeirei Zion in Bricheni. It was attended by delegates from Khotin which was in the hands of the Austrians. It was decided to restart the activities of Zeirei Zion and a local acting council was formed. Even the Shield of Avraham was reorganized and accepted the program of Zeirei Zion. It continued in place until the Holocaust.

A visit of the first delegation of Keren Hayesod was well received in town. There was a large meeting in honor of the emissaries in the courtyard of Pioneer House. The excitement knew no bounds and a large sum of money was collected for Keren Hayesod. Many people accompanied the delegation as it left town.

When the delegation visited Eretz Israel on behalf of the Aliyah movement of Bessarabia and Bucovina, Pioneer House was officially opened and the first group of pioneers was organized. The early years of the Zionist movement were a time of near revolution. Young men and women from good families became pioneers overnight. They left their homes and moved to barracks called Pioneer House where they ate and slept.

They walked in town daily dressed in work clothes carrying their tools on their shoulders and doing hard labor. They stayed in Pioneer House for a few months and finally, on August 23, 1921, they left on Aliyah, Throngs of people came to the train station to say goodbye to them. They reached Haifa on September 24, 1921.

There was also a branch of the Jewish party in Novoselitsa and the majority of the population voted for the Jewish candidates. Between the two wars there was also, in Novoselitsa, the Culture League which attracted the left-leaning youth. They established a library and offered lectures on cultural topics.

In 1920, a kindergarten was created with teaching in Hebrew (organizer - doctor Naftule Rabinovich).

During the Romanian rule the situation worsened and the middle class could not even get loans. The years of drought and heavy taxes were harder on the Jews than on their Christian neighbors who were given more privileges. The situation was so dire that there was mass immigration to South America, Peru, Venezuela, Panama and Ecuador. After many years of hard work of preparation the youth managed to make Aliyah.

Between the two wars there were different institutions that were formed in Novoselitsa: Business and Loan Bank that gave loans to merchants at a low rate of interest, Savings and Loan Bank for small commerce, etc.

In the summer of 1918 there was an area conference of Zeirei Zion in Bricheni. It was attended by delegates from Khotin which was in the hands of the Austrians. It was decided to restart the activities of Zeirei Zion and a local acting council was formed. Even the Shield of Avraham was reorganized and accepted the program of Zeirei Zion. It continued in place until the Holocaust.

A visit of the first delegation of Keren Hayesod was well received in town. There was a large meeting in honor of the emissaries in the courtyard of Pioneer House. The excitement knew no bounds and a large sum of money was collected for Keren Hayesod. Many people accompanied the delegation as it left town.

When the delegation visited Eretz Israel on behalf of the Aliyah movement of Bessarabia and Bucovina, Pioneer House was officially opened and the first group of pioneers was organized. The early years of the Zionist movement were a time of near revolution. Young men and women from good families became pioneers overnight. They left their homes and moved to barracks called Pioneer House where they ate and slept.

They walked in town daily dressed in work clothes carrying their tools on their shoulders and doing hard labor. They stayed in Pioneer House for a few months and finally, on August 23, 1921, they left on Aliyah, Throngs of people came to the train station to say goodbye to them. They reached Haifa on September 24, 1921.

There was also a branch of the Jewish party in Novoselitsa and the majority of the population voted for the Jewish candidates. Between the two wars there was also, in Novoselitsa, the Culture League which attracted the left-leaning youth. They established a library and offered lectures on cultural topics.

In 1920, a kindergarten was created with teaching in Hebrew (organizer - doctor Naftule Rabinovich).

On June 29, 1940 the Soviet army entered Bessarabia. Many Zionist families (about 100 people) were deported to Siberia and all private enterprise immediately ceased. All factories, stores and schools were closed. The language of instruction was Russian. A general inspector who came from the center announced, during his visit to a school where the majority of students were Jewish, that in the Soviet Union everyone is allowed to study in his or her mother tongue. Several Jewish students demanded a Jewish school basing themselves on the inspector`s declaration. A few days later these students were invited to his office at 11PM where they were told that their request represented an instigation against the police.

A year later, when the war broke out and the Soviet army retreated, about 100 people escaped with the Russians. The Romanians came to Novoselitsa on July 7, 1941 and were received with the Christian residents carrying national flags. That very same day there was a pogrom against the Jews and 975 of them were killed. The pogrom lasted 3 days and Jewish belongings were plundered. The market was set on fire and about 50% of the Jewish homes were burnt.

At the end of the pogrom all the surviving Jews were gathered in the Caruso factories on the Bucovina side. They remained there for three days. Lists of names were made and those who had homes untouched by fire went back. Another 49 Jews were arrested and 37 of them were shot out of town. Surviving Jews from surrounding villages were brought to Novoselitsa. On July 24 all the Jews from the villages were sent east without knowing where they were going. On July 27 the authorities announced that the Jews had to leave town.

On the morning of the 29th the entire Jewish population was gathered on the main road by armed young people. 1500 carts were brought to that location and backpacks were placed on them. Some elderly and sick people were also allowed to go on the carts. At noon 20 gendarmes appeared with police officer Yeftudio leading 200 youths from the pre-army brigade. The convoy began to move. On the way to Transnistria they stopped in transit locations and after three days they arrived in Ataki. The head of the District of Soroka in Ataki asked Yeftudio how it was that the Jews did not die on the way and why they had all arrived unscathed. Yeftudio replied that he was given an order to bring everyone to the Dniester River. He is considered one of the Righteous Gentiles.

They slept over in Ataki and in the morning they were told that the Germans, then in Mogilev, did not want to accept the deportees and they were all brought back to Secureni. They stayed there for two days in Jewish homes that had been evacuated by deportees. They were then sent to the Codreni Forest between Secureni and Edinets. There was a temporary camp there where they remained for 5 days. By then people had begun to die of hunger and of exhaustion. From the forest they continued on to Edinets. 30 people who could not continue any longer remained in the forest and died there.

Russian residents of one of the villages of the Casaps brought food to the deportees. In other villages they were robbed. When they finally arrived in Edinets on August 6 they were not permitted to enter the village. They lived on an estate outside of town for 7 days. There was only one well producing good water. Jews were also brought there from other areas. However, the Jews were not allowed to pump water and anyone who tried was shot in place. Diseases were rampant and 20-25 people died daily. The 11 doctors among the deportees were allowed in reside in town and to look after the sick.

After 3 days all the deportees were sent to Edinets and stayed there until August 15, and some until August 20. At that point an order was given to exile everyone to Transnistria. A small portion of the group- 50-60 people- were sent to Mogilev and the majority went to Markuleshty. Everyone arrived in Climautsi Forest where they found Jews from other areas. From there they went to Closhauts on top of the mountain. It was very cold, snow was failing and people began to freeze.

The Romanian policemen escaped into houses and left the Jews on their own. The farmers came out of their houses, robbed the Jews of everything, even the clothes on their backs. The screams of the thieves and the winds mixed together. That night 340 people died. They continued on their way on the next day and spent the second night in the forest. They reached Ataki in the evening and there they were housed in windowless and door less homes. They stayed there, naked and exhausted, until morning. On the following day they crossed the Dniester to Mogilev. The sick were carried by others. Those who could hide remained in Ataki.

The majority of the Jews of Novoselitsa who were deported through Markuleshty died, shot by the Romanian gendarmes. Those who survived were exiled to Bershad and Obodovca.

A year later, when the war broke out and the Soviet army retreated, about 100 people escaped with the Russians. The Romanians came to Novoselitsa on July 7, 1941 and were received with the Christian residents carrying national flags. That very same day there was a pogrom against the Jews and 975 of them were killed. The pogrom lasted 3 days and Jewish belongings were plundered. The market was set on fire and about 50% of the Jewish homes were burnt.

At the end of the pogrom all the surviving Jews were gathered in the Caruso factories on the Bucovina side. They remained there for three days. Lists of names were made and those who had homes untouched by fire went back. Another 49 Jews were arrested and 37 of them were shot out of town. Surviving Jews from surrounding villages were brought to Novoselitsa. On July 24 all the Jews from the villages were sent east without knowing where they were going. On July 27 the authorities announced that the Jews had to leave town.

On the morning of the 29th the entire Jewish population was gathered on the main road by armed young people. 1500 carts were brought to that location and backpacks were placed on them. Some elderly and sick people were also allowed to go on the carts. At noon 20 gendarmes appeared with police officer Yeftudio leading 200 youths from the pre-army brigade. The convoy began to move. On the way to Transnistria they stopped in transit locations and after three days they arrived in Ataki. The head of the District of Soroka in Ataki asked Yeftudio how it was that the Jews did not die on the way and why they had all arrived unscathed. Yeftudio replied that he was given an order to bring everyone to the Dniester River. He is considered one of the Righteous Gentiles.

They slept over in Ataki and in the morning they were told that the Germans, then in Mogilev, did not want to accept the deportees and they were all brought back to Secureni. They stayed there for two days in Jewish homes that had been evacuated by deportees. They were then sent to the Codreni Forest between Secureni and Edinets. There was a temporary camp there where they remained for 5 days. By then people had begun to die of hunger and of exhaustion. From the forest they continued on to Edinets. 30 people who could not continue any longer remained in the forest and died there.

Russian residents of one of the villages of the Casaps brought food to the deportees. In other villages they were robbed. When they finally arrived in Edinets on August 6 they were not permitted to enter the village. They lived on an estate outside of town for 7 days. There was only one well producing good water. Jews were also brought there from other areas. However, the Jews were not allowed to pump water and anyone who tried was shot in place. Diseases were rampant and 20-25 people died daily. The 11 doctors among the deportees were allowed in reside in town and to look after the sick.

After 3 days all the deportees were sent to Edinets and stayed there until August 15, and some until August 20. At that point an order was given to exile everyone to Transnistria. A small portion of the group- 50-60 people- were sent to Mogilev and the majority went to Markuleshty. Everyone arrived in Climautsi Forest where they found Jews from other areas. From there they went to Closhauts on top of the mountain. It was very cold, snow was failing and people began to freeze.

The Romanian policemen escaped into houses and left the Jews on their own. The farmers came out of their houses, robbed the Jews of everything, even the clothes on their backs. The screams of the thieves and the winds mixed together. That night 340 people died. They continued on their way on the next day and spent the second night in the forest. They reached Ataki in the evening and there they were housed in windowless and door less homes. They stayed there, naked and exhausted, until morning. On the following day they crossed the Dniester to Mogilev. The sick were carried by others. Those who could hide remained in Ataki.

The majority of the Jews of Novoselitsa who were deported through Markuleshty died, shot by the Romanian gendarmes. Those who survived were exiled to Bershad and Obodovca.

Sources:

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia. Translated from Russian by Eugene Snaider;

- "Novoselitsa", [in:] Pinkas Hakehillot Romania: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Romania, Volume II. Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1980. Translated by Ala Gamulka, JewishGen, Inc

- The address-calendar of the Bessarabia province for 1912. Ed. B.A.Tapiro. Printing house of the Bessarabian provincial rule, Chisinau, 1911

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

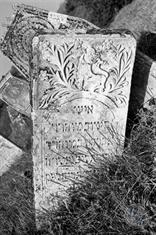

- Boris Khaimovich, Michael Kheifetz. Center for Jewish Art. Jewish cemetery in Novoselytsia

- Postcard collection of Eduard Turkevych

- Russian Jewish encyclopedia. Translated from Russian by Eugene Snaider;

- "Novoselitsa", [in:] Pinkas Hakehillot Romania: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Romania, Volume II. Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1980. Translated by Ala Gamulka, JewishGen, Inc

- The address-calendar of the Bessarabia province for 1912. Ed. B.A.Tapiro. Printing house of the Bessarabian provincial rule, Chisinau, 1911

Photo:

- Eugene Shnaider

- Boris Khaimovich, Michael Kheifetz. Center for Jewish Art. Jewish cemetery in Novoselytsia

- Postcard collection of Eduard Turkevych

- Home

- Shtetls

- Vinnytsia region

- Volyn region

- Dnipro region

- Donetsk region

- Zhytomyr region

- Zakarpattia region

- Zaporizhzhia region

- Ivano-Frankivsk region

- Kyiv region

- Kropyvnytskyi region

- Luhansk region

- Lviv region

- Mykolayiv region

- Odessa region

- Poltava region

- Rivne region

- Sumy region

- Ternopil region

- Kharkiv region

- Kherson region

- Khmelnytskyi region

- Chernihiv region

- Chernivtsi region

- Cherkasy region

- Crimea

- Synagogues

- Cemeteries

- Objects & guides

- Old photos

- History

- Contact

Jewish towns of Ukraine

My shtetl

My shtetl

Donate

Jewish towns of Ukraine